The single most definitive driving force behind Scott Morrison’s climate policy has been avoiding talking about climate policy.

For the majority of the time, it isn’t too hard to achieve. Media and political discourse is mostly reactive and if neither major party wants to talk about climate all they need to do is simply ensure they don’t talk about it. The rest follows neatly.

Sometimes, external global forces make that impossible. In September 2019, a series of global climate strikes drew traction in Australia, and marches filled the streets. Only months after that, the Earth’s climate-intensified atmosphere was the primary driving force behind some of the country’s most catastrophic bushfires. One full year worth of pandemic gave a reprieve, but this year, a drumbeat of climate summits is increasing global scrutiny on the government’s terrible record on emissions, the most recent being a summit held in the US in which Morrison struggled through, grimacing and reproachful.

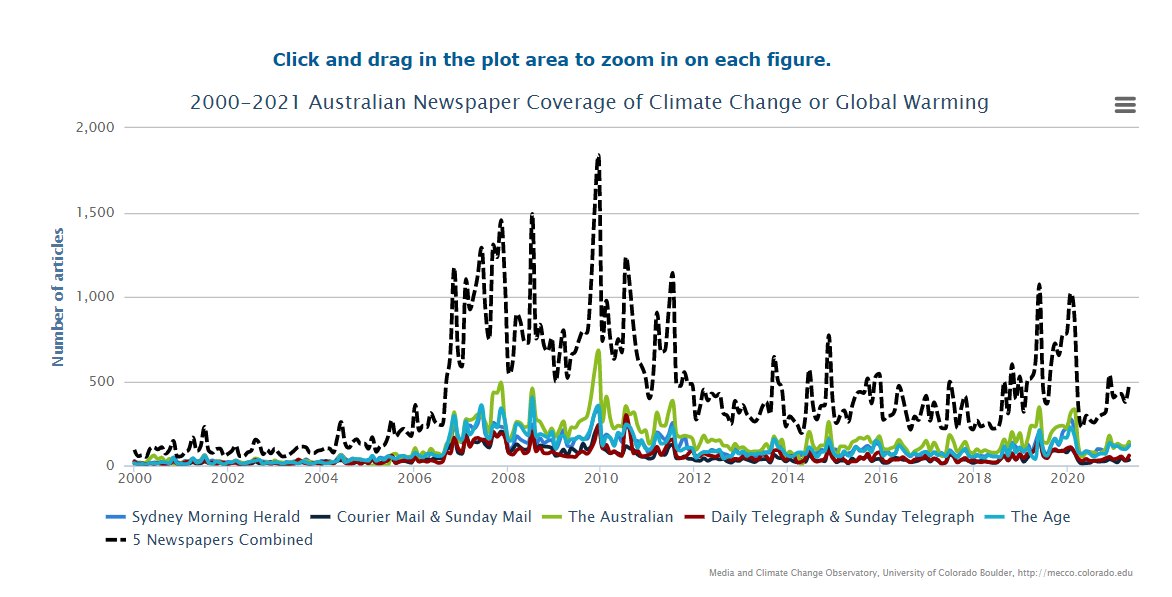

Until June’s G7 meeting, Morrison has a brief respite. Without any external forces drawing attention to climate – whether they’re activist, atmospheric or geopolitical – climate is happily forgotten across political and media discourse. It is neatly quantified by the University of Boulder’s international climate media coverage tracking project, which shows that without major external events drawing attention to the issue, climate change bubbles along as background noise:

And it is reflected in this year’s budget, in which a range of major new projects to worsen emissions through taxpayer funding direct towards fossil fuel projects, alongside a range of missed opportunities to bring on immediate decarbonisation. What little funding there is for climate change goes towards adapting to the consequences of burning fossil fuels, instead of trying to shift the country so it sells and burns fewer fossil fuels.

It’s an ages-old plea, but it’s awful that this isn’t getting more attention. Climate change came up once in Treasurer Josh Frydenberg’s budget speech. 117 words of 3,888. “Technology not taxes,” despite having announced a raft of taxation-funded measures to support fossil fuelled technology. TV caption transcripts available from the Tveeder site show, of the ABC’s coverage of the budget from 19:00 to nearly midnight, climate change came up once, in a question to voters in Perth. Sam, a young Australian about to turn 18, said “I think one of the biggest issues, this budget has done nothing to help the climate crisis. It briefly mentioned it, but no new spending but spending billions on fossil fuels. They are losing potential jobs that could be made in creating the climate change, new energy, public transport and infrastructure.” In less than a minute, that was that.

Yesss! Great to join fierce climate defenders taking the message to Parliament this morn

It’s a disgrace that billions in public money in #Budget21 is going to industries that destroy Country, Climate and Culture pic.twitter.com/Zqpb2VFRGk

— Senator Lidia Thorpe (@SenatorThorpe) May 11, 2021

The Labor opposition isn’t keen to bring it up either. It didn’t feature in the immediate reply from Labor, though it’ll likely be mentioned in official budget reply speech coming two full days after the ink has dried on coverage of the budget. Opposition leader Antony Albanese has not mentioned it on Twitter. Albanese spoke to Today, Sky News, ABC news, Sunrise and 2CC. It was mentioned during none of these interviews, and mentioned a single, brief time during a doorstop on Tuesday the 11th. “They certainly don’t have, still after eight long years, still don’t have a climate policy”. Labor’s shadow minister for climate, Chris Bowen, did at least tweet about it:

Josh Frydenberg’s budget speech had the same old weasel words on net zero emissions.

The budget had no plan, no policies and no vision for an economy driven by new energy.

The world’s climate emergency is Australia’s jobs opportunity. An opportunity this budget misses. Again. pic.twitter.com/jF5S4NbEFP

— Chris Bowen (@Bowenchris) May 12, 2021

Of course, the argument in defence of radio silence on climate change is that the pandemic has worsened a range of major social issues: vulnerable people lacking work, healthcare, aged care and housing all severely impacted by the flow-on effects of COVID19. But what has become clear through the course of the year is that the best-case scenarios for green COVID19 recovery funding are when these social problems are directly addressed through climate legislation.

There are many examples of this. They include energy bill relief through upgrades to households and urban infrastructure, in addition to renewable bringing down the cost of electricity. Major work programs to bring millions of people into the fold in creating the energy transition through the work of their own hands are wildly successful, like Biden’s plan to create 10 million clean energy jobs. COVID19 recovery that aims for equity and focuses on the key concerns that people have in society leads both to reduced emissions and increased wellbeing.

The green and equitable 2050s could be born in the covid-19 recovery of the 2020's. But only if we plan for it. New op-ed. https://t.co/iBpJ3oPSXT

— Dr. Elizabeth Sawin (@bethsawin) December 18, 2020

Climate change is no longer an ‘issue’. It is everything: it soaks into every single compartmentalised subject matter in society. It drives the worsening of pre-existing problems – and climate solutions can drive the curing of those problems, too. A massive, budget-driven project to commence a rapid, immediate decarbonisation of Australia could be transformative. The power, transport and building sectors, in particular, could lead to significant and immediate change. The industrial, mining and agriculture sectors could see business become the true leaders of climate action in Australia. These policies could all be made to align with the most ambitious climate goals. A social-justice and equity focused rapid decarbonisation plan, driven by an aggressive need to solve the impacts of COVID19 and to eliminate emissions ASAP, would be immensely popular.

Tonight we sent a clear message for our Government to #FundOurFutureNotGas by investing in climate solutions & our communities. But @JoshFrydenberg & @ScottMorrisonMP have put their fossil fuel mates first #auspol #Budget2021 pic.twitter.com/kSYZRwNRSH

— AYCC (@AYCC) May 11, 2021

The depth and breadth of the missed opportunity here is something to behold. The only active, effortful actions taken are those that directly or indirectly fund fossil projects. That is a double hit to justice and equity – the harm of those actions is born by everyone exposed to climate and air pollution impacts, but the profits and benefits all flow to the powerful few in charge of those fossil projects. Clean energy could – with the right design – be far more equitable and accessible, with community-owned and distributed alternatives leading to much greater benefits to many more people.

None of this remains likely as long as climate change remains unmentioned. It is very simple and very easy for climate to simply fall off the radar. That means efforts to worsen the problem, and missed opportunities to resolve the problem (while addressing other major social issues), go unchecked.