Forget telling Google or Alexa to turn the heater on, the climate control of the future could be as simple as a spray-on film for your windows.

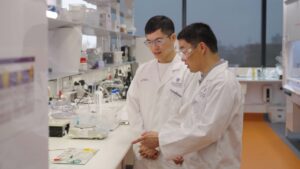

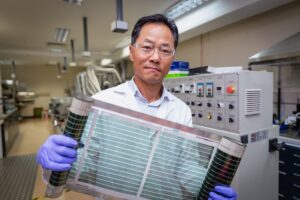

Researchers at the University of Melbourne have developed a vanadium oxide nanoparticle ink – the same vanadium oxide as is used in redox flow batteries – that could be sprayed on to existing windows and building exteriors to moderate the amount of radiation that passes through.

The idea is to create a passive climate control, as the ink is programmed to block or allow more radiation at specific temperatures.

The trick is in the phase-change abilities of vanadium oxides, which can block heat when above a certain temperature. Unfortunately, to date that temperature has been 68°C, a few degrees above the hottest recorded temperature on earth.

But researchers led by Dr Mohammed Taha began playing around with the properties of the substance to get that temperature down to 30°C-40°C.

They were able to change those properties to ‘strain’ or stress the compound, which ramped up the energy within the molecules making them active at a lower temperature. Encasing those molecules in glass nano-spheres created an external stressor, further ramping up the energy within and further lowering the temperature at which the phase-change transformation happens.

The material can be programmed to work at a specific temperature, so it can be optimised for greenhouses or for homes, allowing more solar radiation to pass through during the day and blocking radiant heat from leaking out at night, or vice versa.

What the researchers came up with was a liquid that can be sprayed onto buildings or added to paint, or even added to clothing to regulate temperatures in extreme environments.

Taha believes commercialisation could be as little as five years away — if a manufacturer was interested.

The Australian Greenhouse Calculator says on average Australian homes create some 18 tonnes of greenhouse gases per household each year, or about a fifth of the country’s total annual emissions. which add together to produce at least one-fifth of Australia’s annual greenhouse gas emissions.

In homes that aren’t energy efficient or are not star-rated, heating and cooling can account for as much as 40 per cent of energy use.

For poorly-built housing, a material like the one invented by Taha’s researchers — especially if it could be made cheaply enough — could be a life saver.

The Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute says 18 per cent of renters couldn’t keep their homes warm enough in winter — and that was in 2020 before power prices began to surge — and these people were also much more likely to also report ‘fair’ or ‘poor’ health’.