Europe, including the UK, leads the world on effective energy policy and recently passed a border adjustment tax that will incentivise lower carbon producers who want to sell their products in Europe.

The US in April is expected to announce ambitious new targets, possibly aiming to double the carbon reduction achieved to date by going for a 50% reduction by 2030. President Biden has moved quickly, and yet collaboratively, with his bureaucracy to get things happening.

This leaves Greater Asia with the question of how strongly to participate.

China, Japan and India, three of the world’s largest energy consumers, need access to cheap, reliable energy. They would prefer to produce that domestically if they can, for the sake of energy security. Renewable energy can clearly be produced locally in China and India, and in ITK’s opinion, offshore wind may mean that Japan can also move into that club.

Once these Asian super powers become convinced they don’t need fossil fuel imports, they will move in that direction. In China’s case there is the added problem of its huge domestic coal mining sector with between 3 to 5 million employees. Still, moving away from coal is not a new issue.

In Wales, in East Germany, in Spain and in Kentucky in the US the transition has already happened. There is a broad academic literature on the topic.

But of course carbon emissions and the climate issue can’t be put to one side. If there is one thing that unites us all, it’s that we all live on the same planet, and it’s the planet that’s impacted by global warming.

And Asia, reluctantly perhaps, but nevertheless inevitably will come to the same conclusion as everyone else, carbon emissions have to be eliminated.

So the moves by Europe to impose a Carbon Border tax and the US to strengthen its emissions reduction target will have close to zero immediate consequences for Australia’s thermal energy exports.

The issues for coal in Australia in the first instance will be around finance and insurance, investability and country reputation. These are important but manageable.

The second order problem though is that the US and European markets are major export destinations for many Asian products, from the Japanese car industry, to Indian technology to China’s manufactured goods.

As those markets become harder to access without the “right” credentials, policy in Asia will shift at the margin. It will also shift because in the very, very end governments do eventually act in the interests of their people.

Finally, it would be remiss not to make the observation that Australia will be a competitive green hydrogen producer and maybe that will be important.

However, my feeling at this stage is that in the same way that renewable energy is democratic – that is that most countries have a resource of wind or sun or both – so many more countries will be able to produce green hydrogen than have say gas reserves.

So the global trade may be more competitive. That’s in the future.

Australia is the world’s third largest energy exporter

Energy exports, coal and more recently gas, are super important to Australia and to our trading partners. Australia lags only Russia and Saudi Arabia in energy exports.

The following figure, derived from BP World Energy stats, shows the five largest energy exports and the five largest importers.

The three largest importers are China, Japan and India. China and India are also major producers.

Turning to fossil fuel production as opposed to export/import, Australia is one of the world’s largest producers but much less significant compared to its export position..

Australia built its position in global fossil fuel trade with, so far, about 45 years of steady growth in coal volumes, supplemented in more recent years by LNG.

If you are keen, you can see a plateau in coal volumes in the past couple of years, but to make a useful forecast we will need to answer the central question of Asia’s competing needs for energy and to reduce carbon emissions and the competitiveness of renewable energy v imported fossil fuels.

Oil reduces the positive energy balance of trade

For the 12 months ended January, 2021, Australi’s net energy balance of trade was $71 billion, with the long running decline in oil production, and therefore the need for more oil imports, more than offset by the rise in gas exports.

In looking at the figure below, please note the 12 month trailing average and therefore the temporary impact of last year’s low commodity prices. Also, oil is shown on a net basis.

And finally, even though it’s certainly not news, we repeat that Australia’s coal and gas exports go to Asia and not to either the US or, to any meaningful extent, Europe

The US emissions target

As with Australia, what happens in the US is only partly a function of Federal policy. There is lots of action throughout the economy at all levels of business and state and local government.

Still, from a federal perspective, and focusing for the moment on the “hard” impact as opposed to the equally important “signalling”, the message appears to be that action is coming quickly.

As recently as March 8, the Wall Street Journal noted that Biden administration officials

“have said they plan to unveil a new U.S. target for emissions reductions during a global climate-change summit in Washington next month. It will set a goal for reducing U.S. emissions over the next nine years.”

There is a suggestion that the US may aim for a 50% CO2 reduction from 2005 levels by 2030. Since US emissions are already down 21% from 2005 levels, due to Federal, State, cities, business and local Government action, there is a feeling that 50% is not impossible.

Actions already taken are rejoining Paris, suspending new oil and gas leases on Federal Land, and reopening a dormant $US40 billion land program for clean energy.

However, the more important signals may be the posting of climate change conscious people into key positions within Government agencies. For instance, the leading candidate for a US Treasury “climate hub” is Sarah Bloom Raskin, former deputy Treasury secretary and a known climate hawk.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said at her confirmation hearing: “I think we need to seriously look at assessing the risk to the financial system from climate change..” Raskin is expected to look at tax incentives.

A US National Task Force has been established and has held its first meeting. This task force includes Cabinet level leaders from 21 federal agencies, plus senior White House officials.

The WSJ states that: “The president is planning to unveil in the coming weeks a potentially multi-trillion-dollar legislative package centered on improving U.S. infrastructure and addressing climate.

Advocates say a huge cash infusion like the one Biden is proposing is likely the fastest way to advance the president’s climate goals by investing in technology to capture emissions, deploy more electric vehicles and develop wind, solar and other emissions-free energy sources, plus the massive transmission system to connect them.”

BCG’s suggestions to President Biden

BCG suggested four things that could move the USA faster down the decarbonsiation path. They are all reasonably standard things that any sensible consulting firm or economist would recommend to any Government.

First: Build the base by focusing federal spending and tax credits on building more a more competitive based for EVs and renewables. That creates employment.

Second: Offer incentives for infrastructure investment in areas such as renewables, transmission, grid reinforcement. Provide support to State for EVs, energy efficiency, distributed energy resources paired with ambitious targets. Offer regulatory incentives for building efficiency

Third: Leverage Federal Authority where appropriate, eg disclosures, building codes, fuel standards, Government EV fleets

Fourth: Consider a carbon tax or if that is impossible politically WTO border mechanisms to mitigate the risk of carbon leakage.

The first two points made by BCG, one of the world’s leading consultancy firms, in relation to the US are of course just as, or even more applicable to Australia.

Europe leads the decarbonisation drive, but will pass the ball to US

Europe, and we include the UK, is a decade ahead of the rest of the world in decarbonising its economy. Europe has an effective carbon price backed up by a wide range of other policies.

Recently, the European Commission’s proposal for a “carbon border adjustment mechanism” passed European Parliament, as part of a wider package of laws aimed at cutting the EU’s emissions by 55% below 1990 levels before the end of the decade.

As Euractiv states the border tax is necessary as the European carbon price increases from its current level of around Euro 30 to say Euro 40 over the next 10 years, that will make carbon intensive European products less competitive.

Industries most likely to be impacted are steel, cement and chemicals.

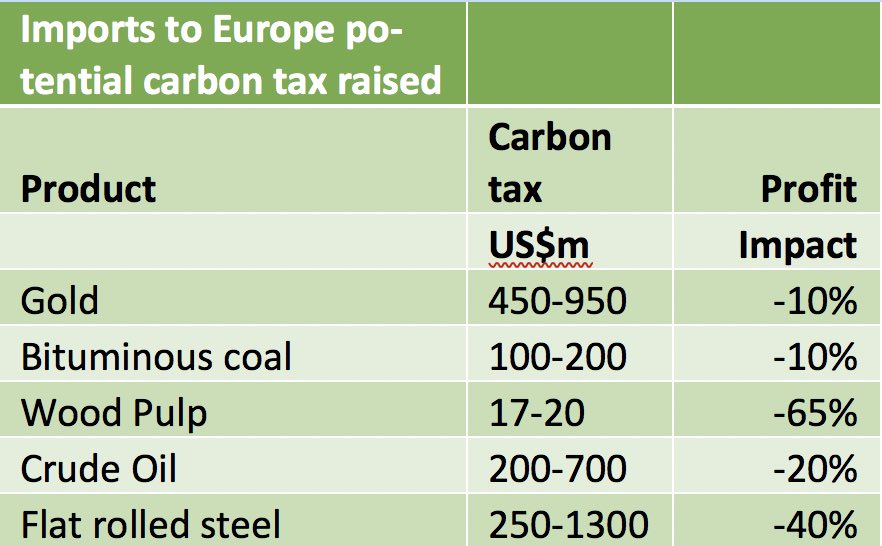

Well known consulting firm BCG wrote a piece back in June 2020 looking at its potential impact and assume a levy/tax of around $30/t.

BCG stated:

“The levy could reduce profits on imported flat-rolled steel, in particular, by roughly 40%, on average. The impact of the added costs would be felt far downstream….. European manufacturers may find that the cost of Chinese or Ukrainian steel that is produced in blast furnaces now compares less favorably with the cost of the same type of steel from countries that require more carbon-efficient methods, for example. Similarly, European chemical producers may cut their reliance on Russian crude oil and import more from Saudi Arabia, where extraction leaves a smaller carbon footprint. “

The following figure is becoming increasingly familiar to those of us that follow this topic:

Despite the anti climate change, anti Europe politicians to be found in the federal parliament of Australia, BCG also notes:

“It must also be noted that even in sectors that would be directly impacted, the EU carbon border tax would account for a very small portion of their overall cost base. Although it could translate into a 50% cost increase for producers of ethylene, for example, the tax would add only about 1% to the retail price of a soda sold in a plastic bottle.”

As estimated by BCG tax raised and profit impact in Europe for key products were:

Blast furnace and basic oxygen furnaces emit about 2 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of product in steel manufacturing but that can be halved using electric arc furnaces.

The impact on Australia

Australia exports around $20 billion of goods and services to Europe (including the UK). Around $7 billion or 35% was gold ,which BCG identified as majorly exposed to the border tax. Most gold is produced by “bad carbon” countries like China, Russia, and Australia.

If the adjustment is implemented at the company level some off grid producers in Australia might look OK, but at the country level you might expect European producers to prefer production from perhaps the US or Canada.