Introducing new policies – such as the capacity market pushed by the Energy Security Board – without a total explicit statement of the carbon implications is beyond the pale in this day and age.

If coal is to be kept, and gas is to be supported, policy makers had better be able to explain to the youth of today why the Integrated System Plan (ISP) is wrong, why global warming implications should be ignored and why it’s the most cost effective way to do it.

The overwhelming need is new investment in bulk energy and, to an extent, in new dispatchable resources. Will the ESB’s policy favour new dispatchable capacity? As far as I can see, only in a minor way.

In the end, a capacity market is an insurance policy. It may be worth the cost of having insurance, but insurance will be a lot less expensive if the underlying system is working the way it’s supposed to – and that means lots more bulk energy.

In ITK’s view, even if some form of availability insurance is needed, the costs would be lower and total system security would be enhanced if coal closure dates were known with more certainty.

Blueprint Institute, linked below, outlined back in 2020 how this could be done, but their report was ignored by most.

In ITK’s view, simple things like certainty of coal closures, REZ-wide modelling, building the interstate connectors, the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) actually delivering on improving its ability to connect new generation, could accomplish a lot and at relatively low cost.

It’s the coal closure plan, no doubt politically difficult, that is the fundamental blockage; that, and frankly the difficulty of getting new generation connected.

The ESB’s reform process seems so far to have completely overlooked the basic building-block of the new system and that is the bulk energy supplied by wind, solar and variable renewable energy (VRE). Where is the policy development to ensure that the National Electricity Market (NEM) gets the bulk energy it needs?

What is the point of focusing on the insurance “capacity payments” when we haven’t got the building blocks in place?

Sure the ISP provides a license to build transmission, but although it shows that wind and solar provide the lowest cost NEM consistent with the reliability standard, neither the ISP nor federal government policy provide a way for the VRE to be built.

The ESB, AEMO, the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) – and naturally the Australian Energy Regulator (AER) – remain deadly silent on the issue.

The federal government remains silent, other than transmission loans and maybe equity, and these are not really the problem.

All the heavy VRE lifting has to be done by the New South Wales and Victorian governments, which have legislation and policies, and then there is the “here you go mate” Queensland press release way of getting things done.

As a result, the major gen-tailers – not just, but mainly Origin Energy, AGL Energy and EnergyAustralia (EA), as well as Shell (owner of ERM) – have slacked off and abrogated their duty.

I especially single out Origin because Origin has all the peaking generation anyone could require, with gas generators in Queensland, Victoria, NSW and South Australia and it could have built endless wind and solar farms and actually lived up to the model that its partner Octopus has demonstrated can easily be marketed.

But it hasn’t done it. Instead Origin complains about “where is my coal?”

EnergyAustralia has little funding for capacity at present, except for pumped hydro and batteries, and AGL doesn’t know whether it’s Arthur or Martha, neither or both, but at least it has some wind development sites.

Gen-tailers have to earn their social license

Social license apparently has four stages, rejection, acceptance, approval and trust. Notwithstanding some

improvements in net promoter scores, where a positive score represents approval, electricity gen-tailers

are arguably stuck at the lower end of the spectrum.

And indeed, I’d argue that they’d be even lower if consumers realised that gen-tailers are not fulfilling their basic obligation, which is organising sufficient supply by buying big and long and selling small and short.

Rather, they are somewhat in the nature of the “billing operators” so brilliant satirised by John Clarke and Brian Dawes in The Energy Market explained in 2017.

The final ISP is due soon

The final version of the Integrated System Plan (ISP) will be delivered sometime soon. The final will be the responsibility of Merryn York’s team, whereas the draft release was from the team headed by Alex Wonhas.

The final ISP will incorporate policy development and other news between the date of the draft and the date the final ISP was set. The modelling for the final ISP will likely have concluded well before the release date and, in my experience, big reports are often, by necessity, already behind the times when they are released.

Since the ISP is ostensibly – and in reality – a transmission planning document that provides the “authority” and “social license” at the system planner level to develop various transmission links, it likely won’t include anything from the ESB’s capacity scheme, except insofar as it impacts transmission.

The two big things that the final ISP will have to allow for are the Victorian government’s offshore wind policy and the closure of the Eraring coal plant. Also there is the Waratah battery and what storage, if any, that has actually been confirmed to FID status by Origin.

Contrary to the harsh comments I have made about Queensland’s lack of policy, and which really go to what is the plan for coal generation in that state, there is in fact a series of announcements which in total could be regarded as a substitute for actual policy. These include calls for storage projects and the like.

For interest, can you really take seriously as a policy statement something like:

“He (Mr De Brenni ) told reporters at Wivenhoe the government was looking for 5-7GW of new storage, indicating a mix of pumped hydro and battery storage. “We’ve already seen $11 billion of investment in wind and solar …. and we will continue to fund more mega projects.”

Nothing in writing, no justification for the number, etc. Just a casual press conference comment. Reminiscent in its own way of the Bjelke Peterson way of doing things: “If the chickens squawk, feed them.”

I guess Queenslanders are used to this style of government. I doubt, though, that it gets factored into the ISP because it doesn’t represent policy and there is too much uncertainty.

A very interesting presentation by Ben Cerini from Cornwall Insights at this year’s Sydney Smart Energy Conference showed that offshore wind in Victoria will reduce storage requirements.

More broadly, ITK thinks that Victorian offshore wind will also help to maintain Victoria’s current position as an energy and power provider in the NEM. Under the draft ISP the modelling outcomes indicated a decline in Victoria’s position and a rise in Queensland’s share.

Regarding Eraring, it seems clear that new generation will have to be brought forward. This is easier to do in a model than it is in the real world.

More broadly, the current situation with coal generation outages must surely have emphasised the risks

of not going hard enough on new supply.

There are two gas power stations under construction, for better or for worse, and these should be able to

fill in the gap caused by the Snowy 2 delay.

It’s mainly bulk energy that’s needed; not a capacity market, or more gas

The ESB has been charged to continue its development of a capacity market. I’ll say not too much about

that in this already long piece, but for my money the name is wrong. It should be an “availability” market. Nothing is more useless to consumers than paying for capacity that actually doesn’t deliver when required.

More broadly, though, the focus on capacity ignores what we at ITK perceive as reality, and that is that what we really need is lots more bulk energy.

The ISP cost modelling doesn’t select more gas generation it basically selects lots of wind and solar and most distributed storage.

To be sure, the distributed storage depends on the assumption that household battery prices will decline and so far (over the last eight years or so) that hasn’t happened. But there is still every reason to think it will, at some point.

ISP calls for 32GW of new wind and solar by 2032, but only 6GW of storage

What I, personally, find the most frustrating thing about the current situation, and which leads to a lot of venting, is this idea that we have to have lots more gas for generation and/or lots more firming in the way of batteries and pumped hydro.

That’s not what the ISP modelling shows. The ISP modelling calls for 26GW of new wind to be installed between 2024 and 2032, 6GW of utility solar and 6GW of storage. Additionally, 18GW of behind the meter solar are installed and 11GW of behind the meter storage.

If you look at the way the ISP modelled storage in terms of MW and what, given the input assumptions, was the efficient way to provide it, we see:

It doesn’t have to work out like that, of course; utilities could install more storage, but for the big gen-tailers that seem so reluctant to invest in the transition having customers do the spending must seem attractive.

It might be that incentivising behind-the-meter storage, and it could happen via a capacity market I guess, could move the system along while we wait, like Godot, for household battery costs to come down in the way that no doubt they are modelled to in the ISP and which no doubt underpins the modelling results.

My main point, though, is it’s very clear we need lots of wind investment; 26GW and probably more, rather than less, to be on the safe side. Better to over-build than under-build. 26GW, say $50 billion of total capital and, if done correctly, about $15 billion of equity over 10 years is actually an easy finance task.

What’s not easy is sourcing the turbines, sourcing the people, running the GPS models, negotiating the land owner compensation and, of course, ensuring the transmission and social license issues are managed.

REZs are expected to help greatly with the overall process and provide the interface point between government and the private sector. Government also ensures one way or another than the transmission is there.

Big retailers lack social license

In Australia, it really shouldn’t be the role of government to run the revenue risk. It should be the retailers doing that job, and that’s the complaint. The big gen-tailers just aren’t doing their share. Retailers need social license as much as transmission companies and wind and solar companies.

Electricity retailing is a relatively new industry in Australia. There was no retail sector before privatisation.

And so you can in one way, as an ignorant industry, excuse the industry’s poor reputation – that was created by (i) over use of doorknockers (ii) possibly unethical pricing – that forced the government to introduce a default market offer [DMO].

Today, though, I do find it difficult to excuse retailers not fulfilling their basic role. What is that role? It’s essentially to buy big and long and sell small and short.

Retailers make a profit because the cost of buying big and long is less than the cost of buying small and short. Retailers cover the risk of big and long by spreading sales over many customers, thereby statistically ensuring that their load is effectively long and diversified against the risk of any one customer.

As previously noted, the Big Three gen-tailers have two-thirds of the contestable NEM customers and about 50% of all NEM operational (ie not rooftop) volumes.

If they don’t go big and long in wind farms their customers are forced to bypass them and the wind farm developers are forced to bypass them. Government is forced to step in to cover the risk and effectively do the retailers’ job. The benefits of privatisation, namely that competitive markets ensure marginal revenue = marginal cost, are lost.

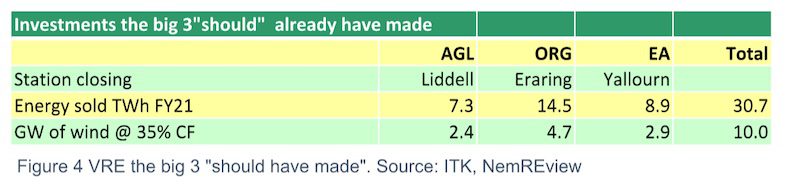

Based on those numbers, if the Big Three were to do no more than maintain market share – and there is a strong case for leadership, not just hanging in the pack – if they do their bit, it implies taking responsibility for about 13GW of wind and 3GW of utility solar over the next decade.

One could add in Shell as the fourth-largest retailer by volume. Snowy is doing its share of VRE contracting, a point often overlooked by its critics.

From another perspective, the Big Three “should,” already, in the past 18 months or so have committed to something like 10GW of new projects.

Each can point to some PPAs that have been signed years ago, but very little since the closure dates were

announced and generally not directly in the region serviced by the plant closing.

Taking responsibility means either directly building, owning and operating the generation assets or signing PPAs that directly cause others to build own and operate the 13GW of wind and 3GW of solar.

Again, my personal view, one shared by almost no one, is that in the long run the skills that are required to develop and operate a large portfolio of wind and solar are better kept in-house.

Yes, it takes a lot of capital, but by having a big portfolio with separate teams dedicated to sites, to GPS, to managing the supply chain and logistics, to managing sales to managing opex, will in the end provide “a right to operate” or trust.

In every walk of life, and certainly in business, there is a learning curve. By investing in wind and solar development, operation and ownership a large gentailer can walk down the learning curve and end up more profitable than competitors.

If the big gen-tailers choose to buy in all their wind and solar, assuming they actually stay in the market at all, they will eventually see a major VRE supplier emerge that will have what Porter calls “supplier bargaining power.”

History shows that generation and retailers go together – so either the retailer buys the generator, or the generator buys the retailer.

AGL does have some wind farm developments in the wings and a potential partner and these could cover the closure of Liddell in terms of energy, but there is no way they will be operating by Liddell closure. ITK will be amazed if even two of them get to FID by mid 2023. Unless Grok is in control.

Coal closure plan would dramatically reduce capacity risk

A defined coal closure timetable would greatly reduce the costs of an availability or capacity market because there would be far more certainty about what was needed to replace the lost energy and power.

The ISP models all brown coal to be gone in Victoria by 2030 and a sharp reduction in QLD. The pace of change modelled by the ISP “step change” scenario is seen by the industry as the best view for planning, but still not endorsed by policy support except for transmission. And therefore you can’t plan to it really.

A defined coal closure plan would surely be lower cost and more efficient than all the drama and legislation of a capacity market. Or so it seems to me.

The Blueprint Institute offered an excellent plan for managing coal plant reduction. See: Phasing down

gracefully. But in general, any plan would be better than the current shemozzle, where information is at

a premium and therefore decisions are being made in a fog.

Events this week will increasingly focus the market’s attention on the fact that, for one reason or another, coal generation can be counted on less and less.

But we still don’t know what’s going to happen to various generators including Loy Yang A and Loy Yang B in Victoria; Mt Piper and to an extent Bayswater in NSW; and with the exception of Gladstone there is no public information on what, if any, plans there are for the future of coal generation in Queensland. Even Gladstone

represents circumstantial, rather than direct, evidence.

Victoria

In Victoria Loy Yang B gets its coal from Loy Yang A’s coal (mud) pits. It may be possible for LYB to continue beyond a closure of LYA, but I wouldn’t feel too confident about it. In any event, it’s the sort of thing a closure plan could provide certainty around.

In the Victorian government’s mind it seems that the offshore wind is at least part of the threshold for the

closure of coal generation, but a target of 4GW by 2035 will not be nearly fast enough to replace all Victorian

coal generation, in and of itself.

And in any event for the time being the cost estimates of offshore wind are such that there will need to

be a lot of benefits for Victorians to be better off.

Queensland

Queensland remains the great unknown. The position remains that Queensland’s coal generation fleet is, on average, younger than those in the southern states. Michael De Brenni, the state energy minister, stated last year in Parliament that “there is no present intention to close any coal station.” He is still expected to make a

major statement about Queensland energy policy sometime this year. Our understanding is that the date for

that statement gets pushed back and back.

It may be that the Queensland government has a plan around when coal generators in Queensland will be closed and is organising its state-owned generators, Stanwell, CS Energy and CleanCo, to build sufficient new plant ahead of the internally scheduled closures.

That may be, but it’s certainly not public. And because it’s not public it runs its own risks, including, in my opinion, likely a lack of any competitive ethos other than three Queensland generators each trying to be first in queue to get some money from the government and build new generation.

“Supercharged ISP:” Is it a thing?

It was encouraging to see federal energy minister Chris Bowen announce unanimous agreement between federal and state ministers to develop a “supercharged ISP,” which is to cover the entire Australian energy transition.

I quote from the press conference:

“So, we need, what I call, a supercharged ISP, which deals with hydrogen, which deals with all the energy sources, which deals with transmission and which deals with all the things necessary for this transition. Ministers unanimously agreed with that.

“As I said, Labor, Liberal and Greens, from the largest jurisdiction to the smallest, agreed that we would progress that work and we would take what I call a supercharged ISP and turn it into a national transition agreement which covers all the work necessary.”

This plan is expected to be progressed by the next ministers meeting in July, although as there was a meeting on Friday June 17, events may have overtaken what was said on June 8.

But in reality there is no chance of a detailed plan being ready by July. I should have thought it would be a struggle to come up with an ordered table of contents in just four weeks.

Of course, it can be done, the whole world can – according to some people – apparently be made in six days. But for us mere mortals it’s a bit of a bottler.

Rather than speculate what will be in that plan, which I suppose could, conceptually, include targets for renewable energy shares, targets for coal closures, targets for hydrogen production and a lot of other stuff; it’s probably better to just file under forthcoming and wait and see.

As I’ve said previously, in my view it’s Queensland that could most benefit from being able to “blame” the federal government. “They made me do it, but look they gave us some goodies.” Still, that’s a political perspective, not my scene.

It is interesting to observe that the federal minister will come up with a whole-of-energy-sector plan that will get the agreement of all states in just a month, but the Queensland government will struggle for at least a year to come with a plan for electricity in Queensland.