New modelling by the University of Sydney and ETH Zürich published this week examines a surprising new way of thinking about achieving climate goals. Currently, the easy majority of climate models, particularly those published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Chance (IPCC), assume the continued growth of gross domestic product (GDP) across the world, whereas this research considers what is known as ‘degrowth’.

“Degrowth is defined as an equitable, democratic reduction in energy and material use while maintaining wellbeing,” writes the University of Sydney. “A decline in GDP is accepted as a likely outcome of this transition. It focuses on the global North because of historically high levels of energy and material use in affluent nations, thereby enabling a just transition mindful of poverty especially in low-income nations”.

The research was carried by lead author Lorenz Keyßer, from ETH Zürich. It was done in Australia under supervision of Professor Manfred Lenzen, from the University of Sydney’s centre for Integrated Sustainability Analysis (ISA) in the School of Physics.

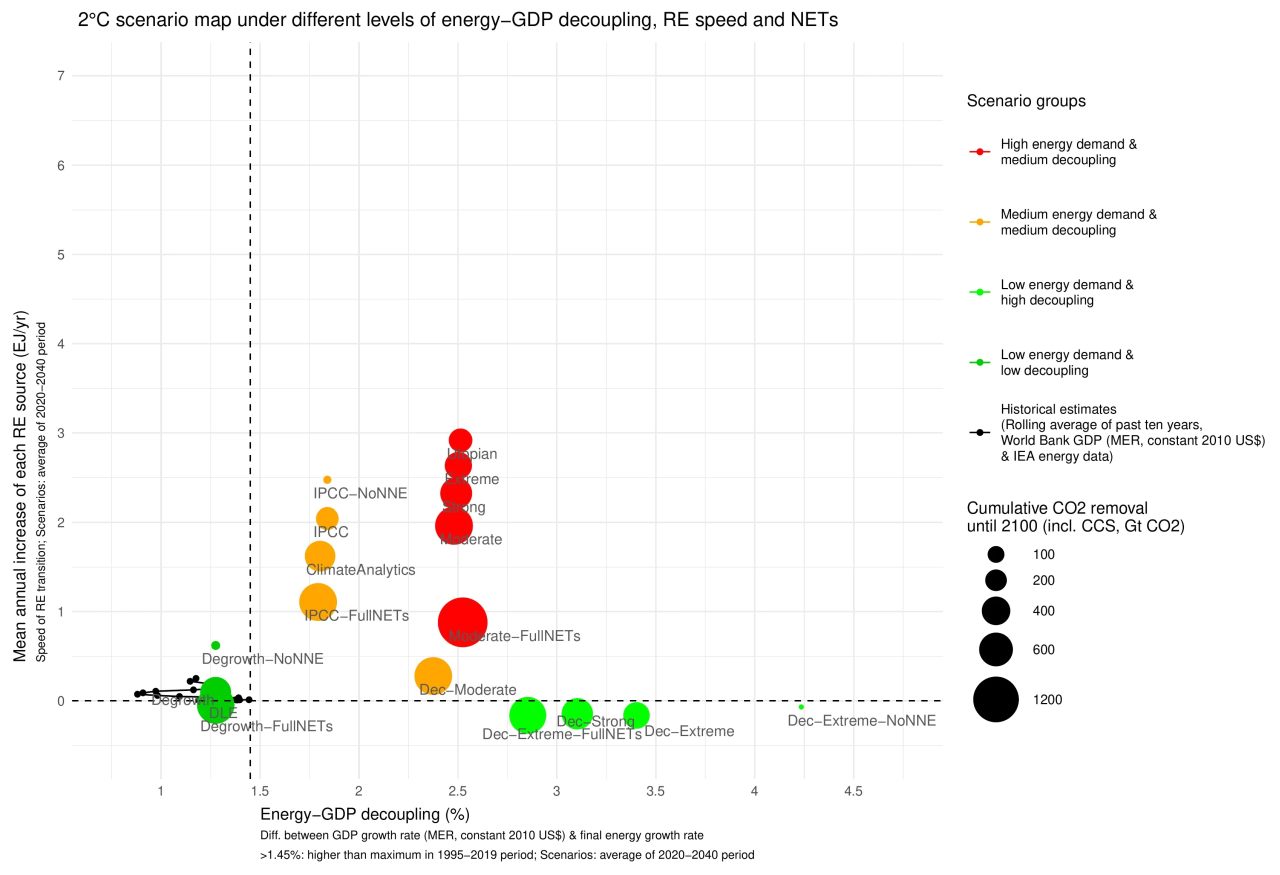

One of the challenges addressed by exploring a potential decline in GDP is that it means models of climate action rely less on problematic technologies to achieve emissions reductions. “Deployment of controversial ‘negative emissions’ future technologies to try to remove several hundred gigatonnes [hundreds of billion tonnes] of carbon dioxide assumed in the IPCC scenarios to meet the 1.5⁰C target faces substantial uncertainty,” Professor Lenzen said. The models also focus on reducing growth in the Global North, while increasing access to energy and decreasing poverty in the Global South.

The authors emphasise that ‘degrowth’ is focused on satisfying the needs and wellbeing of people, particularly around wages and employment. But it assumes that a shrinking economy is welcomed. Real-world examples include a shorter working week, universal basic services such as food and healthcare and limitations to income and wealth. These ideas feed into various scenarios that allow climate targets to be met through a mixture of existing renewable energy technologies paired with a notable decrease in demand for energy. This leads to a reduction in reliance on carbon removal, including carbon capture and storage.

The authors highlight that while there is an advantage in these scenarios in relying less on unproven technologies, degrowth is itself an unproven political concept. “Compared with technology-driven pathways, it is clear that a degrowth transition faces tremendous political barriers”. Degrowth “challenges deeply embedded cultures, values, mind-sets and power structures”, and as such, will face steep barriers not just to adoption but even discussion and conceptualisation in many countries. However, the research paper does not call for the immediate adoption of this concept, but rather a greater consideration in the modelling work of key climate bodies.

“Clearly, degrowth would not be an easy solution, but, as indicated by our results, it would substantially minimise many key risks for feasibility and sustainability compared with established, technology-driven pathways. Therefore, it should be as widely and thoroughly considered and debated as are comparably risky technology-driven pathways”, write the authors.

In Australia, economic growth plays a key role in climate debates. During the 2019 federal election, much of the criticism of the Labor opposition’s climate policies centred on the purported impact decarbonisation would have on economic growth. And even among groups urging climate action, most modelling focuses on highlighting the likelihood that economic growth occurs either unimpeded or only slightly affected by decarbonisation policies.