Momentum builds to curb the rapid growth of natural gas. This week saw Australia’s friends and allies, the U.S. and European Union and other country partners formally launch the Global Methane pledge, an initiative to reduce global methane emissions.

More than 100 countries, representing 70% of the global economy and nearly half of anthropogenic methane emissions, have now signed onto the pledge, which commits signatories to reduce global methane emissions by at least 30% from 2020 levels by 2030. Australia refused to sign.

Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas and is worse for the climate than coal over the short term. It is over 80 times more powerful than CO2 on a 20-year view. Methane is the principal component of what is branded ‘natural gas’.

Twenty years is the critical timeframe for reaching the Paris Agreement target of halting temperature rises to less than 1.5 degrees C, a trajectory the world is sorely missing at the moment.

Methane emission reduction is vital to curbing the worst effects of climate change. It makes up at least one quarter of all greenhouse gases.

Methane from the oil and gas supply chain accounts for 23% of emissions, while coal mining accounts for 12%.

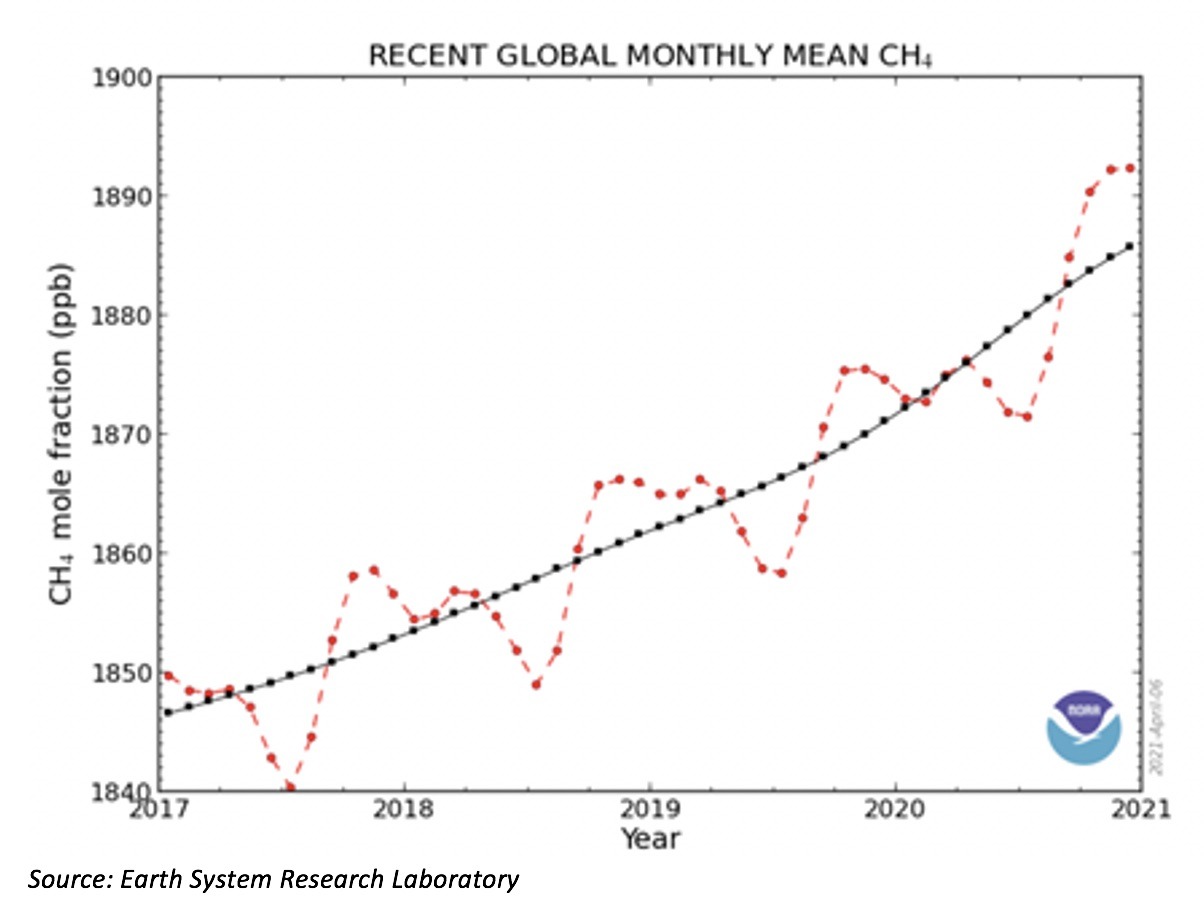

Far from declining, during 2020 methane emissions grew at the fastest rate since records began in 1982, despite it being a COVID-19 recession-affected year.

Since 1990 methane emissions have grown by a considerable 25%. It is little wonder a Global Methane pledge has become a necessity.

This year, it is expected that methane emissions will continue to rise at an even faster rate as the production of the highest fossil fuel emitters – oil, gas and coal – has recovered.

The easy road to reducing methane emissions by 30% by 2030

“Cutting methane emissions is the best way to slow climate change over the next 25 years.” Inger Andersen, Executive Director, UNEP

It is highly unlikely that signatories have already created detailed roadmaps on how they will reduce methane emissions by 30% by 2030 as the Global Methane pledge dictates.

There are, however, some easy-to-implement measures they could use that will quickly reduce methane (or as it is commonly called, ‘natural gas’) consumption and hence emissions.

In many countries, it is now cheaper to heat a home with renewable electricity and more efficient to heat hot water with a heat pump and cook with an induction cooktop.

Some governments have already implemented programs to encourage a switch of energy that will result in reduced methane emissions.

The US, for instance, has implemented a methane leak fee on gas that never reaches the customer of up to US$1,500/tonne. This will encourage the gas industry to clean up its business, reduce venting and fix municipal and supply chain gas leaks.

Essentially, the U.S. has recognised that to meet its climate change commitments, it has to tackle the methane issue. The U.S. gas industry has struggled to secure capital in recent years and has been unprofitable for most of the last decade.

The methane leakage fee is a ‘polluter pays’ fee. It will have little effect on the economics of gas in the U.S. as gas prices have risen so strongly that it will be comfortably absorbed.

With pre-existing technology, a 75% reduction in methane from the oil and gas sector is possible; 50% of this could be done at zero net cost.

Using basic measures, signatories could comfortably achieve the global methane pledge of a 30% reduction by 2030.

Methane – or gas – cannot be a transition fuel any longer, anywhere in the world

As IEEFA has previously noted, methane is a very big danger to the climate and governments are only just waking up to its powerful effects, especially in light of the need to reduce emissions in the necessary short 2030 timeframe.

Over the years, many governments around the world have fallen for the marketing line run by the gas industry that gas is a “transition” or “bridge” fuel. It is not. Gas is a high emitting fuel when the full lifecycle is taken into account.

China, Russia and India are three of the top 6 global emitters of methane. Clearly their non-participation in the pledge to reduce methane is not helpful.

China is the world’s largest methane emitter. It is expanding the use of all fuels – including renewable energy – as it rapidly develops.

Russia is a massive ‘natural gas’ producer and the major supplier to Europe — and increasingly to China — through the Power of Siberia pipeline. As such, gas is a major foreign exchange earner for Russia, and the methane pledge rubs up against its historically weak climate change commitments.

India is a fast developing nation and has clearly defined targets to produce 500 gigawatts (GW) of renewable energy by 2030. Despite its rapidly growing renewables investments, India sees gas as a lower emitting fuel.

While gas has less particulate pollution and is a relatively cleaner burning fuel compared to coal, wood or dung, it is not clean on a lifecycle basis due to venting, flaring and gas leaks across the supply chain.

Australia, the world’s biggest exporter of LNG, also didn’t participate in the methane reduction pledge. Instead, the Australian government is continuing to push through a “gas-fired recovery” post COVID-19.

The government is heavily subsidising companies in the production of gas and LNG and is attempting to open up new gas fields in almost every state and territory. Instead of reducing emissions, the Australian government wants to see the gas industry – and emissions – grow.

The fact that a major emitter – the U.S. – has signed up and led the initiative along with Europe is very positive, as is the inclusion of top emitters Brazil and Indonesia.

Three of the top six methane emitters have signed the pledge which is a great way to begin.

As with all pledges, they start with a few interested countries. We expect membership of the methane pledge to gather momentum over time, and in-country strategies to develop to move out of oil and gas extraction.

Author: Bruce Robertson, LNG/gas analyst with the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA)