We have just entered the first days of summer in Australia, and it’s worth pausing for just a few moments to reflect on the stunning Spring that has all but sealed Australia’s leap towards a green energy future.

Never have so many governments, utilities, corporates and investors promised so much in such a short period of time for such an important outcome.

Yes, making promises is different to delivering on them, but the sheer scale of the announcements over the past few months has been extraordinary – from new emissions and renewable targets, new projects, the possibility of opening new manufacturing industries, and a promise to fast-track the closure of Australia’s dirty coal plants.

At the same, the country’s main grids have set new benchmarks for the penetration of renewables, and shown an extra layer of reliability despite the high levels of wind and solar. And the market operator has also set out new engineering pathways that show that – yes – 100 per cent renewables can be done.

Consider what we have seen in the past three months…

States of play

Victoria, with the country’s only remaining brown coal generators, in October set a new 95 per cent renewable energy target for 2035, and lifted its 2030 target to 65 per cent. The Labor government has been re-elected for another four year period.

Queensland, the state most heavily dependent on coal, in September set an 80 per cent renewable energy target by 2035, including a vow to close all the state owned generators by that time.

Western Australia vowed to close down the last of its state-owned generators by 2030 and pledged $3.8 billion to fund the transition to green energy, including money for new renewables, battery and other storage, and grid infrastructure.

NSW, the state with the country’s biggest coal fleet, in November launched the first of up to 20 tenders for new renewables and long duration storage as it kicked off its plan to be ready to replace the entirety of its coal fleet if they all retire – as many predict – in the next 10 years.

Having already reached net 100 per cent renewables, the ACT government has embarked on its next series of auctions, seeking wind and solar capacity to power the electrification of everything, and is rolling out new gas free suburbs.

In South Australia, the government is fixated on a new green hydrogen plan at Whyalla, which it hopes will be as fundamental and important a move as the Tesla big battery that was built in less than 100 days in response to the state wide blackout in 2016, and which changed the thinking about battery and inverters in the grid.

Corporates come to the party

There were not just new government targets, there are also planned exits and big corporate plays.

AGL, under pressure, from shareholders including tech billionaire Mike Cannon-Brookes, in September announced the accelerated closure of its remaining coal assets, Loy Yang A and Bayswater.

AGL in November also announced the early closure of its ageing Torrens Island B gas generator units, to be replaced by the big battery currently under construction, with the precinct to be transformed into a clean energy and manufacturing hub.

Canadian asset giant Brookfield – once a suitor to AGL – joined in an agreed bid for Origin Energy, which is closing its last coal plant in 2025, with plans to spend $20 billion on new renewables and storage by 2030.

Trevor St Baker, one of the last noisy holdouts for a coal-based grid and economy, in September cashed in his chips with the sale of the Vales Point coal fired generator to a Czech investment outfit.

Big, bigger, biggest

As the country’s biggest coal owners were heading for the exit, there was an abundance of new project announcements, both real and imaginary.

Acciona announced a doubling of the country’s biggest wind farm, at MacIntyre, to 2GW. The first 1GW stage is already under construction.

Victoria’s biggest wind project, the 756MW Golden Plains wind farm, was financed on a “merchant” basis, meaning it has yet to find any customers. The project could end up being double that size, with plans to go to 1.5GW.

Neoen signed a landmark deal to provide 24/7 power – with wind and battery storage – to BHP’s massive Olympic Dam mine in South Australia. That will see a new 300MW/800MWh battery, and pave the way for the expansion of what could be the country’s biggest wind, solar and battery hybrid facility at Goyder South.

CWP Renewables became the first company to secure a connection agreement to install a big battery next to an existing wind farm at the Sapphire wind project in northern NSW.

Heading offshore

Global energy giants continue to try and carve out a niche in the country’s nascent offshore wind market, boosted by new federal legislation that will deliver the country’s first permits, and the determination of Victoria to have 9GW of offshore wind capacity by 2040 to help replace the coal generators that will retire.

In the last few months, Ørsted, Iberdrola, Tepco, Equinor and others confirmed their interest, joining a host of heavy hitters including Macquarie’s Corio, Shell, Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners, and a number of smaller players.

Some of these projects are huge in Australian terms, sized at 2GW or more, but even bigger projects were being outlined and developed on land, with an eye to hydrogen exports and/or green manufacturing.

Iron ore billionaire Andrew Forrest, in between his relentless attacks on the fossil fuel lobby, announced a new 10GW renewable super hub in north Queensland, and continued work on another massive wind and solar hub in southern Western Australia.

Forrest’s companies have also begun construction on the first stage of a multi-gigawatt wind and solar hub in central Queensland, and is nearing completion of the country’s first electrolyser factory.

Made in Australia?

There is serious talk about creating domestic production of solar modules and wind turbine components in Australia, as some of the massive hydrogen export projects are toned down to concentrate on local manufacturing, and the opportunities of exporting goods of added value, thanks to low cost wind and solar.

This could be helped by the biggest project of them all, the Sun Cable 20GW of solar and 42GWh of battery storage, which is destined to help power Singapore via a sub-sea link (probably easier than shipping green molecules as hydrogen and ammonia) and which will spark interest in domestic manufacturing opportunities.

This is an important re-framing of Australia’s worth as an economic force from one focused on fossil fuels, where it remains among the top three exporters in the world, to one focused on clean energy- although it has stiff competition, including from the US thanks to Biden’s Inflation Reduction Initiative.

A season of records

Spring was also a season of records, as it often is thanks to its good wind and solar conditions, the mild weather and the relatively low demand.

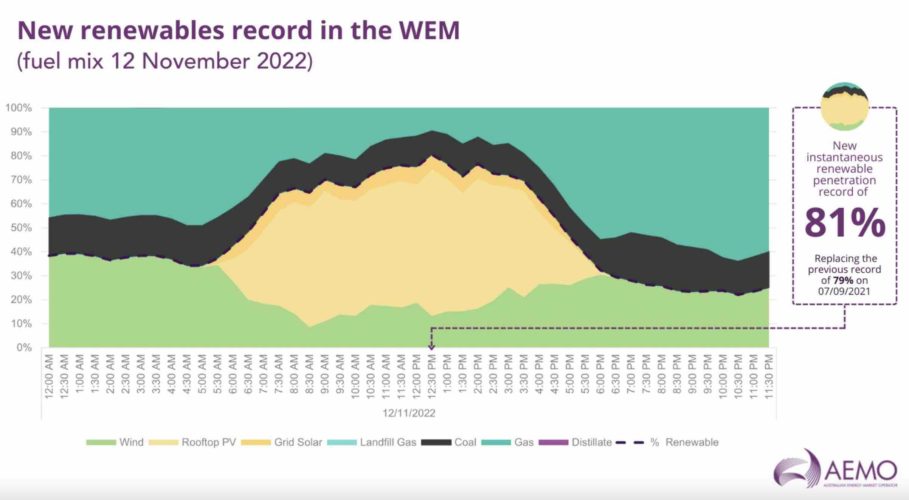

The share of renewables in the main grid hit a peak of 68.7 per cent in October, and 81 per cent on the WA grid, which is all the more remarkable as it is completed isolated. It is the world’s biggest of its type. Numerous records were set for the output of wind, solar and battery storage, and new minimum demand levels too.

Of course, these are just moments in time, often as brief as five minute intervals. If Australia is to reach its climate targets it needs to go a lot further than 68% renewables for a 30 minute period in 2022, it needs to reach an average of 82 per cent renewables over a full year by 2030.

The Australian Energy Market Operator ended Spring by publishing a new roadmap to 100 per cent renewables, which lays out the path to running the country’s main grid for hours, and then days at a time on renewables only. A decade ago that was unthinkable. To some, it still is.

Committed to clean energy

All of this – the bold state renewable targets, promises of coal and gas closures, and proposed giga-scale projects – will not happen without a huge effort, co-operation, capital investment, social licence, a “just” transition plan for workers and deep analysis of the technical challenges.

But what we do know after this remarkable Spring is that Australia now has the will to do it, despite what you might hear from the Coalition and conservative media still struggling to come to terms with the massive rebuttal at the polls across the country in May and in Victoria just last week.

That’s probably the biggest gift of having a federal Labor government swept in at the polls in May, along with the strong community independents and a good showing by the Greens, is that – with voter support – the parliament seems genuinely committed to the green energy transition and delivering on the Paris agreement.

What are we here for?

Australia’s performance in Egypt, support for the Rewiring the Nation program, the rollout of its EV and transport policies, and the support for key agencies such as the CEFC and ARENA have changed the mood across the country.

And, for almost the first time, federal government ministers are even visiting wind and solar farms. There is still much to do – and Labor could, and will need to, do more. But the attitude is the polar opposite of the denial and disgrace of the near decade of Coalition government.

As federal energy and climate minister Chris Bowen said himself at the Egypt COP: “If we’re not trying to keep to 1.5°C then what are we here for?” Despite the concern about new coal and gas projects, and its reaction to the hit on consumer bills from the soaring cost of fossil fuels, it looks as though it is still trying.