Just how bad a situation are Australian energy markets in? We are told, repeatedly, by the architects, managers and regulators of Australia’s National Electricity Market that it is the most efficient in the world.

But lingering questions about the state and fairness of the market are being brought to the fore – by soaring gas prices, the controversy over high electricity prices in South Australia, and as the country grapples with the pace of the extraordinary energy transition that looms over the incumbents.

Authorities are still not sure whether to see this as a massive burden or an incredible opportunity, and there is no great expectation that this week’s meeting of state and federal ministers will provide more than a collection of bandaid and interim measures, rather than paving the way to the widespread reform that is clearly needed.

That’s because energy policy, rather absurdly, remains a partisan issue. Ideological blocks against climate science are reflected in the lack of any environmental outcome in the goals of the NEM, and a prejudice against new technology.

Even more disturbing is the power of the incumbent industry, which has been so successful in controlling the regulatory and policy framework that what should be a relatively cheap energy system is one of the world’s most expensive. The utilities are laughing all the way to the bank, and the mainstream media is looking the other way.

Australia, as fossil fuel proponents are keen to note, has more than enough sources of cheap energy, primarily coal. But by the time it gets to the consumer, its cost has multiplied ten-fold, courtesy of the massive margins taken at the generation, network and retail level.

Analysis of recent trading in South Australia has highlighted the similarities between what is occurring in Australia and what happened in California in the early 2000s, when market manipulation attributed to Enron and bankruptcies brought that state’s economy to a halt through a series of massive blackouts.

There is no suggestion that such blackouts will occur in Australia – apart from those (mostly incumbent generators) campaigning against more renewable energy in the system – nor that there is necessarily anything illegal occurring in the energy markets.

But what we are seeing, according to the Melbourne Energy Institute, is the almost unfettered use of market power and some trends in bidding practices that resemble closely the events that led to the dramatic energy shortages in California more than a decade ago.

Three things stand out, says MEI’s Dylan McConnell: the “economic” withdrawal of certain generators, a big rise in the disparities between the costs of generation and the prices asked, and a change in bidding patterns that takes advantage of constraints in network.

Investigation by the US Federal Energy Regulation Commission into Enron and the Californian power crisis found that high prices were more due to economic withholding by a pivotal generator than to market fundamentals. McConnell suggests similar forces are at play in South Australia and the rest of the NEM.

First on the margins, which we reported on last week, and which David Leitch documented more than a week earlier. These are also known as “spark spreads” – the difference between the cost and the normal price gained on the market from generators.

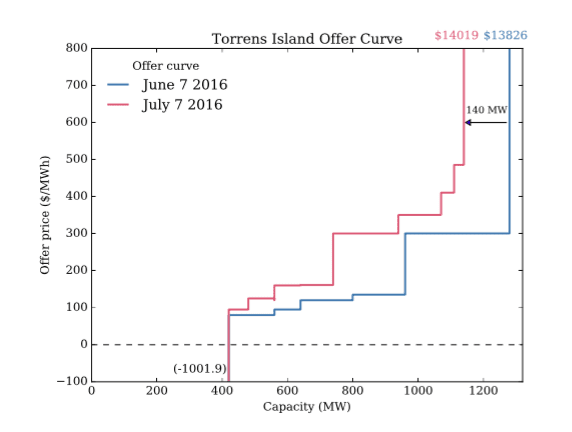

Before June 2016, the South Australian spark spread averaged $17.34, comparable to other markets such as the UK. But since June, after the closure of the Northern coal generator, with gas prices soaring and gas supply issues, and constraints on the electricity network, the spark spread is estimated to have increased by between $40/MWh (at AGL Energy’s Torrens Island gas generator) and $60/MWh (Origin Energy’s Quarantine generator).

Before June 2016, the South Australian spark spread averaged $17.34, comparable to other markets such as the UK. But since June, after the closure of the Northern coal generator, with gas prices soaring and gas supply issues, and constraints on the electricity network, the spark spread is estimated to have increased by between $40/MWh (at AGL Energy’s Torrens Island gas generator) and $60/MWh (Origin Energy’s Quarantine generator).

During this period, McConnell noted, the volume of sales also increased. He said such behaviour contrasts with typical price volume trade-offs expected in efficient markets.

‘Gaming’, FERC said, is taking unfair advantage of the rules and procedures … to the detriment of the efficiency of, and consumers in … the markets. ‘Gaming’ may also include taking undue advantage of other conditions that may affect the availability of transmission and generation capacity.

‘Anomalous market behaviour’, FERC said, is behavior that departs significantly from the normal behavior in competitive markets that do not require continuing regulation or as behavior leading to unusual or unexplained market outcomes.

It cited evidence for such behaviour as withholding of generation capacity under circumstances in which it would normally be offered in a competitive market; unexplained or unusual re-declarations of availability by generators; unusual trades or transactions; and pricing and bidding patterns that are inconsistent with prevailing supply and demand conditions, e.g., prices and bids that appear consistently excessive for, or otherwise inconsistent with, such conditions; and unusual activity or circumstances relating to imports from or exports to other markets or exchanges.

MEI has documented instances of nearly all these in South Australia’s high-price events in early July, and many have already been substantiated by investigations by the Australian Energy Regulator in its market assessments, although its report into the highest priced events are still to be completed.

MEI points specifically to instances of ‘gaming’ and ‘anomalous market behaviour’ – pointing the finger at Snowy Hydro’s Angaston Power Station which it says physically withheld generation. It also looks at evidence that Torrens Island economically withheld generation capacity, and in its rebidding behaviour, including one instance where an extra 140MW of capacity was withheld to the highest price band.

MEI points specifically to instances of ‘gaming’ and ‘anomalous market behaviour’ – pointing the finger at Snowy Hydro’s Angaston Power Station which it says physically withheld generation. It also looks at evidence that Torrens Island economically withheld generation capacity, and in its rebidding behaviour, including one instance where an extra 140MW of capacity was withheld to the highest price band.

The primary issue is the lack of competition, and the ability of a few players to dominate the market – a situation that the Australian economy witnesses in so many sectors. Some of that lack of competition is the result of decisions taken by the Coalition government a decade ago when they chose to privatise the assets.

They sold the network, but kiboshed a proposal to add competition by building a new inter-connector. They also sold the Torrens A and Torrens B gas plants as one, rather than two different generators as had been recommended. They got a higher price by doing so, but consumers are now paying the cost.

South Australia is seen as the proverbial “canary in the goldmine” as far as the energy transition in Australia goes. The main lobby group had been hoping for an “armageddon” that could result in its reinforcing the position of incumbent regulator by strengthening the rules and policies that favour those incumbents.

The hope is, however, that the opposite occurs, and the energy ministers look at what has been happening in energy markets – including the king’s ransom demand for energy security by a handful of generators in the same market – and push the regulators to act with more haste, and more bite.

A host of different rule changes are currently under consideration that could increase competition, mostly by removing the stranglehold enjoyed by the very gas-fired generators accused of market “gaming”, and opening up the market to new technologies, particularly battery storage.

California, which has a much higher renewable energy target than Australia, is already going down that path. Australia should also be at the forefront of the shift to an “energy democracy”, given its extraordinary solar resources and the high take-up of the technology by consumers.

In fact, there is possibly no other industrial sector where consumers have such opportunity to challenge the power of the incumbents. Rooftop solar, battery storage and smart software is giving consumers the potential to go off-grid, to share energy, to trade electricity, to create micro-grids, and to build community-owned generators and retailers.

The potential for that change is underlined in the MEI report. It says the options to address the South Australia situation range from boosting the amount of gas-fired power, as favoured by the incumbents, to encouraging storage options such as batteries and solar towers, and to encourage more interconnection.

In the longer term, South Australian experience points to the need to diversify low emissions generation and storage portfolios.

“As we necessarily decarbonise the national electricity system and increase renewable energy penetration, technologies such as storage and solar thermal will become increasingly necessary to provide for both peak capacity and reliability of supply,” it says.

One thing it won’t need, is more “base-load” generation. As RenewEconomy pointed out last week, there is no room for additional baseload in the state, just for more “flexible” capacity such as storage. The MEI reinforces that, and says that the baseload need in South Australia is for “minus” 210MW.

One thing it won’t need, is more “base-load” generation. As RenewEconomy pointed out last week, there is no room for additional baseload in the state, just for more “flexible” capacity such as storage. The MEI reinforces that, and says that the baseload need in South Australia is for “minus” 210MW.

But many of these options – apart from cutting the line altogether – are difficult to obtain because the rules are stacked against new competitors. The coincidence of a range of factors has contributed to a rapid and unprecedented rise in the concentration of market power.

And until the federal government has a vision and a policy that provides certainty beyond 2020, then that energy transition is not likely to happen as easily and effectively as it should.