The International Energy Agency has challenged the claim by the global thermal coal industry that centralised coal-fired generation is the best solution to energy poverty – where more than 1 billion people in Asia and Africa still go without power.

Over the last year, the coal industry has tried desperately to revive its flagging fortunes by saying coal was the only technology that could deliver cheap electricity for the 1.3 billion without electricity.

It’s been a key line from Peabody Coal, the world’s biggest miner, whose “Advanced Energy for Life” advertising campaign describes energy poverty as “the world’s No 1 human and environmental crisis”. Rio Tinto has used the same argument, and it has been echoed by conservative commentators. Even the Australian government has bought into it, with environment minister Greg Hunt accusing environmentalists of being “against electricity” because they did not support the use of coal to address energy poverty.

But, according to the International Energy Agency, the conservative Paris-based body, coal is not the best option. If coal was to be used, it would have to include carbon capture and storage, which apart from not being commercially available in power stations, would be very expensive. The best alternative, it says, is solar.

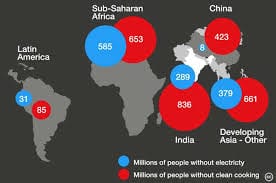

The IEA, in its latest Solar Roadmap publication, notes that nearly 1.3 billion people did not have access to electricity in 2011, mostly in Africa and developing Asia.

“By 2050, although population growth will concentrate in cities, hundreds of millions of people will still live in sparsely -populated rural areas where off-grid solar systems would likely be the most suitable solution for minimum electrification,” it says.

India, one of the countries most affected by energy poverty, has around 400 million people without direct access to electricity. New Prime Minister Narendra Modi has announced a goal of delivering some form of power to all its citizens by 2020, but he will do so using solar.

The IEA assumes grid extension for all urban zones around the world and around 30 per cent of rural areas, and for the remainder, mini-grids and stand-alone solutions. But in both on-grid and off-grid situations, it says solar PV has “considerable merits”.

It notes that people who earn between $1 and $2 a day can spend as much as 40c of those earnings on dry batteries, kerosene and other energy products. PV – provided that finance is available to help with upfront costs – could prove competitive.

The IEA thinks that by 2030, around 500 million people with no access to electricity could enjoy the equivalent of 200W of solar PV capacity. This would be equivalent to 100GW, not far short of the total solar PV deployment to date, and would be entirely in mini-grid and off-grid situations.

“Solar electricity is actually competitive, but up-front costs, ranging from $US30 for very small PV systems to $US75,000 for village mini-grids, are usually too high, even if off-grid systems of several MW are now economically and technically feasible.”

The main problem is financing risk. But once this risk is alleviated, equity funds and debt financers from commercial banks and private funds can be tapped in decentralised rural electrification projects.

Some organisations, such as the Australian-led Pollinate Energy, have been doing just that. Bigger commercial players have also been entering the market, with US-based Sun Edison recently announcing it would install solar PV micro-grids in 54 remote Indian villages. Each installation would involve 241kW of solar PV with battery storage.

IEA executive director Maria Van der Hoeven says even in large cities, many people would not have an on-grid solution. Van der Hoeven says there will be an opportunity for all kinds of fuels, but if the world was to move ahead in the fight against climate change, then carbon capture and storage needed to be priced in. This would make coal even more expensive.