Among the pages of dense, scientific language in Friday’s latest U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Changereport are two key areas that deserve special attention: sea level rise and a recent slowdown in global warming.

The new report incorporates new information on the melting of Greenland and Antarctica, data that had prevented the Nobel Prize-winning panel from making confident projections of sea level rise in its previous reports.

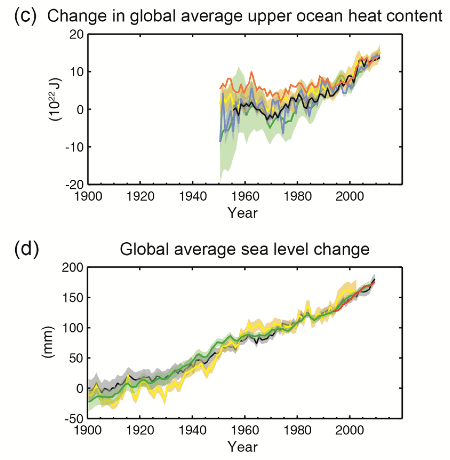

Global average sea level projections based on scenarios of greenhouse gas concentrations.

Global average sea level projections based on scenarios of greenhouse gas concentrations.

Credit: IPCC Working Group I.

Meanwhile, the slowdown in the rate of warming in recent years has attracted the attention of skeptics of manmade climate change, who argue that climate computer models failed to anticipate the slowdown, which they say calls into question longer-term projections of a warming climate.

By significantly raising the projected rates and amounts of sea level rise through 2100, the IPCC is sounding alarms for coastal cities worldwide, many of which are already being forced to adapt to increased flooding. The devastation wrought byHurricane Sandy in New York in 2012 drove home the lethal combination of long-term sea level rise and extreme weather events, and the IPCC’s projections show that urban planners have a major challenge.

For example, a recent study on coastal flooding of the world’s largest coastal cities found that Hong Kong has $60.7 billion sitting at or below the 100-year flood level. That study found that if no actions are taken to boost Hong Kong’s flood defenses, coastal flooding could put $140 billion in infrastructure at-risk if sea levels rise by 15.8 inches.

Sea level rise is one of the most visible effects of climate change, and the report found that sea levels are increasing more rapidly than in previous decades. During the 1901-2010 period, the report said, global averaged sea level rise was 0.07 inches per year, which accelerated to .13 inches per year between 1993 and 2010.

The IPCC’s four scenarios of the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere through 2100 all show faster rates of sea level rise compared to that observed during 1971-2010, the report said.

The new report projects that global mean sea level rise for 2081-2100 will likely be in the range of 10.2 to 32 inches, depending on greenhouse gas emissions. However, the report notes, as other studies have found, that local amounts of sea level rise could be much higher in some coastal areas.

The scenario with the highest amounts of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere shows a mean sea level rise range between 21 and 38.2 inches, which would be devastating for many highly populated coastal cities at or near current sea levels.

Rising sea levels can combine with extreme weather events to flood coastal infrastructure, as occurred during Hurricane Sandy in 2012 at the Hoboken, N.J., transit station.

Rising sea levels can combine with extreme weather events to flood coastal infrastructure, as occurred during Hurricane Sandy in 2012 at the Hoboken, N.J., transit station.

Credit: Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

The sea level rise projections in the report’s Summary for Policymakers were higher than those contained in the draft document before it underwent government review. They were also much higher than the projections in the 2007 report, which projected a global mean sea level rise of 7.1 to 23.2 inches by 2100, but it did not include the influence of rapid melting of the Greenland ice sheet as well as portions of Antarctica because not enough information was known at the time.

Because of the long atmospheric lifetime of CO2, with about 15 to 40 percent of emitted CO2 remaining in the atmosphere longer than 1,000 years, as well as the lag in the ocean’s response to warming, Friday’s IPCC report said that sea levels would likely increase for centuries beyond 2100 and global average air temperatures would remain at elevated levels as well. This notion of the “irreversibility” of global warming on human timescales underscores the need to begin making emissions reductions in the near-term, scientists and policy makers said.

Warming Slowdown and Climate Sensitivity

The report also addressed the controversial recent slowdown in the rate of global warming, noting that the report states that the rate of warming over the past 15 years is about 0.09°F per decade, which is smaller than the trend since 1951, which is about 0.21°F per decade.

The report said that natural climate variability, such as volcanic eruptions, solar cycles, and “redistribution of heat within the ocean” are the most likely causes of the short-term hiatus in warming. “Trends based on short records are very sensitive to the beginning and end dates and do not, in general, reflect long-term climate trends,” the report said.

At a press conference, authors of the report cautioned against concluding that climate models can’t project global temperature change, since many of them accurately capture the longer-term climate record. The report itself said that climate models are “not expected to reproduce the timing of internal variability” in the climate system.

Thomas Stocker, co-lead author of Working Group I and a climate scientist at the University of Bern in Switzerland, said there have not been sufficient studies examining the causes of the hiatus that would have allowed the report’s authors to make more conclusive statements.

“There is not a lot of published literature that allows us to delve deeper at the required depth of this emerging scientific question,” he said. Stocker said another 20 years without much warming, along with continued high emissions of greenhouse gases, would be required before serious questions about the accuracy of climate models would be raised.

“This question (of the warming slowdown and model projections) will certainly also be looked at by the scientists in the coming years,” Stocker said. “It is not concluded with our assessment but I think we have made an important first step to put some numbers on the table.”

Most of the extra heat being put into the climate system by greenhouse gases is going into the oceans, accounting for more than 90 percent of the energy accumulated between 1971-2010, the report found. In recent years, deep ocean heat content, particularly in the Southern Ocean, has increased rapidly even while global air temperatures have slowed their rate of increase.

Increase in the heat content of the upper ocean since the 1940s.

Increase in the heat content of the upper ocean since the 1940s.

Credit: IPCC Working Group I.

“That doesn’t mean that the ocean saves us from global warming,” Stocker said. “It means that there would be much more powerful (shorter-term) global warming if it wasn’t for the ocean”

Scientists said the ocean heat content would yield further increases in global temperatures in the coming years, as the heat slowly percolates through the ocean layers and enters the atmosphere.

The report found a major jump in the total manmade contribution of energy to the climate system — with a 43 percent increase between the estimate in 2005 and the estimate for 2011, the report found. That is due to continued growth in greenhouse gas emissions and lowered estimates of the cooling influences of aerosols, such as dust and particulate matter in the atmosphere.

Like previous IPCC reports, the draft also contains a range for the “equilibrium climate sensitivity,” which is essentially an estimate of how much warming would occur if the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere were to double.

The draft shows a likely climate sensitivity range of 2.7°F to 8.1°F, down from the 2007 IPCC report that pegged it at a “likely” range of 3.6°F to 8.1°F.

Climate scientists said the slight change is insignificant, and in no way indicates that climate change is likely to be less severe than previously projected, as many skeptics have argued.

“For those who want to focus on the scientific question marks, that is their right do so,” said Michel Jarraud, the secretary general of the World Meteorological Organization, in a press release. “But today we need to focus on the fundamentals and on the actions. Otherwise the risks we run will get higher with every year.”

This story was first published at Climate Central. Reproduced with permission.