This note is nothing more than an annual reminder of the climate data. It’s a reminder of how hard many people work.

ChatGPT found a Tyndall Centre reference showing that between 1990 and 2021, 130,000 journal articles dealt with some aspect of Climate Change – that’s about 4,194 a year, which is over 11 articles a day world wide, every day for over 30 years.

I read some of these articles. The amount of modelling and the sophistication of the modelling is staggering.

For the science to be consensus, findings need to be triangulated and replicated. Data monitoring from satellites from ocean buoys and from a great many other sensors is collected unceasingly. The science doesn’t just look at the here and now, but looks backwards as far as possible and projects forwards as far as possible.

It’s just a massive amount of brain power that goes into understanding the climate and yet the conclusions that are reached seem sometimes only to be paid lip service.

Despite what the popular media might write, when you do the work you would have to be an absolute nutter to conclude anything other than that the quality of life for the future generations is at risk.

The ongoing concern is that a number of indicators such as ocean heat content, sea level rise, glacier loss and the global temperature annual increase all show signs of acceleration over the past decade.

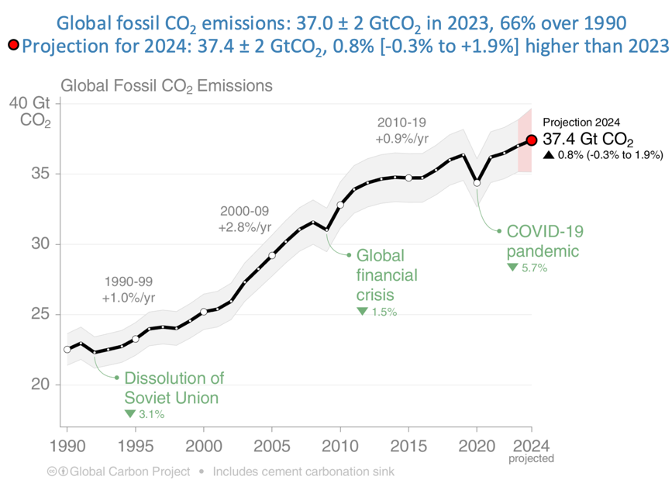

On the positive side, there is a slow down in 2024 of the growth in emissions, still higher than 2023 but only about 1%. Equally despite the vast wealth created by the extraction of fossil fuels the ongoing increase in energy is increasingly sourced from renewables.

The most cited paper in 2024 dealt with ocean circulation currents which are part of the changes in the ocean that also have many other impacts and which are discussed belowt. The next most cited dealt with economic impacts.

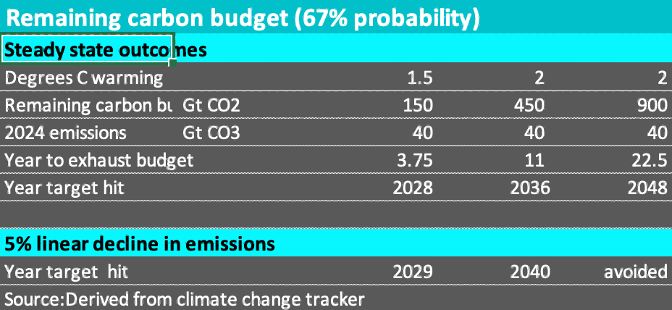

The remaining carbon budget is the estimated amount of CO2 that can be released before hitting some warming target. Such things are full of uncertainty. I assume we want to be at least 2/3 confident of hitting a particular target.

Figure 1: Remaining carbon budget

In essence, global policy sort of aims towards zero emissions by 2050. This requires a linear decline, that is a reduction in emissions each year of something over 5%, but 5% gets you close to zero.

If that could be achieved, then 2°C would be avoided, but 1.7°C would soon happen. Realistically, 1.5°C is locked in and 1.7°C is a very safe bet. On these numbers, 2°C is still within sight.

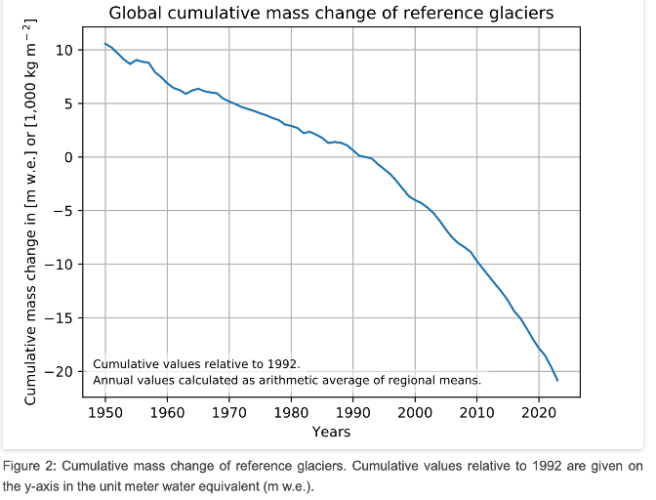

Ocean Heat Content surges in 2024

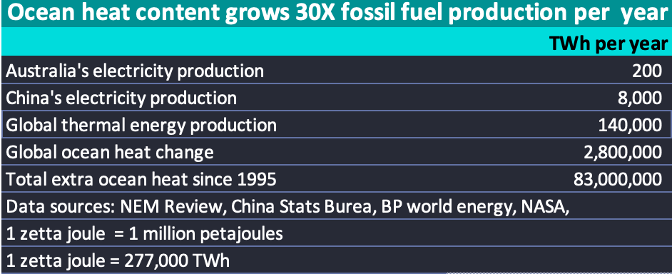

My homepage has from day 1 contained a table comparing electricity production from various countries and total global thermal (oil, coal and gas) energy production with the annual change in Ocean Heat Content (OHC).

Thermal energy is for transport, ie cars, planes etc, for electricity, alumina smelters etc. Up until about 2023 the annual change in OCH was about 28-30 times global thermal energy production.

Figure 2: Ocean heat relative to electricity. Source:BP, Cheng, ITK

One thing that table doesn’t cover is the recent acceleration in OHC. Look at the slope of the red bars compared to the blue in the following summary figure. The 16 ZJ increase in 2024 is a bit over 30 times total thermal energy production.

The 2024 Cheng et Alia OHC update is worth a careful read.

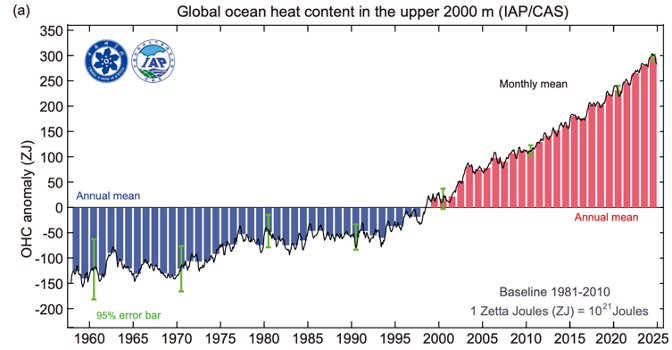

Glacier Melt

The figure below is the cumulative impact of glacier melt of reference glaciers using 1990 as the reference (zero impact year). The vertical (Y) axis is either in water or (so I read) equivalents metric tonnes square metre. Who knew a square meter of a glacier weighed so much.

Figure 4: Glacier mass change: Source: glacier monitoring bureau

In practice, and no doubt some people will question the validity of such photos but in this case I most certainly don’t.

Figure 5: Pederson Gacier

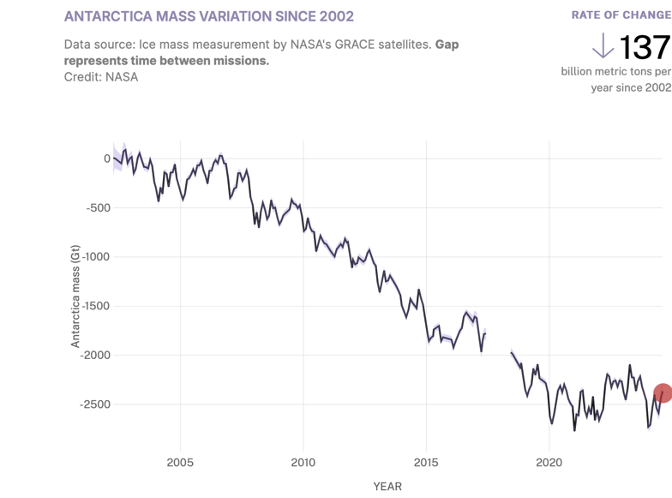

Antarctica Ice loss

NASA has conducted satellite based measurements of Antarctic ice loss since 2002. Its very clear ice is being lost.

Figure 6: Antarctic mass variation. Source: NASA

However, in general it’s difficult getting surface and under ice based data and understanding what precisely is happing in an area that, together with Greenland, contains about 2/3 of all the freshwater on Earth.

The Australian Antarctic program puts it thus:

Figure 7: Glacier diagram: Source Australian Antarctic Program

However useful the satellite data is at measuring the size and movement of ice shelves in Antarctica, they aren’t going to help with understanding that warmer water may have on making the ice shelf slide of its rock base at a faster rate.

So this is an area that some of that AI money that social media platforms are throwing around could arguably be invested.

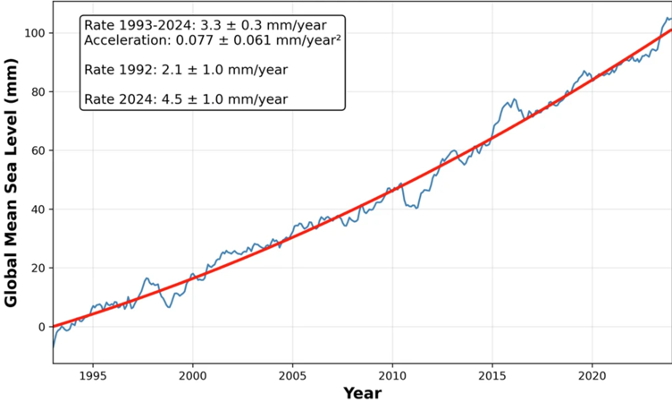

Sea level rise

Like OHC, the rate of sea level change is increasing. A summary of the 2023 data is:

The rise in globally averaged sea level—or global mean sea level—is one of the most unambiguous indicators of climate change. Over the past three decades, satellites have provided continuous, accurate measurements of sea level on near-global scales.

Since satellites began observing sea surface heights in 1993 until the end of 2023, global mean sea level has risen by 111 mm. In addition, the rate of global mean sea level rise over those three decades has increased from ~2.1 mm/year in 1993 to ~4.5 mm/year in 2023.

If this trajectory of sea level rise continues over the next three decades, sea levels will increase by an additional 169 mm globally, comparable to mid-range sea level projections from the IPCC AR6.

Sea level rise has been measured by satellite radar and has been done so for over 30 years.

In the 1990s sea level rises were about 2 mm per year. In recent years they are well over 4 mm a year.

Figure 8: Global sea level rise, Source: NOAA

Sea levels have risen 0.1 metre since 1990. If one simply assumes a constant rate of acceleration of 0.06 mm/year then by 2050 sea levels are rising 19 mm per year and cumulatively will be up by 0.36 metres. Simple extrapolation without any good theory is a poor way to forecast and all I am doing is talking about a default rate.

Sea levels rise for two main reasons. (1) Thermal expansion as the ocean heats and (2) melting ice from glaciers and Antarctica. Calculations show that melting ice is responsible for 2/3 of the change and 1/3 from thermal expansion. These are extremely broad brush strokes.

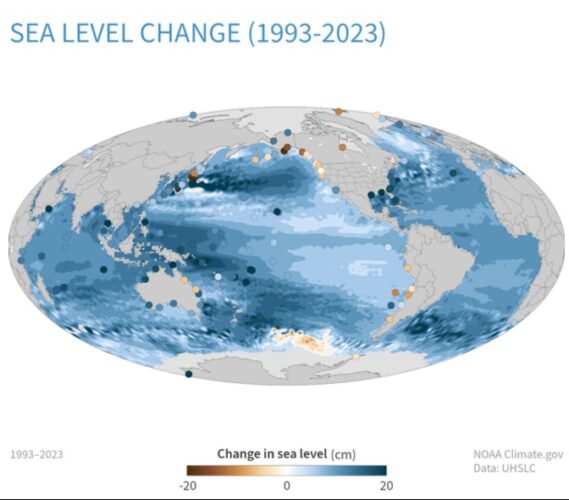

However, the real point is that 100 mm is a global average. Sealevel change is not even and is driven by earth’s gravity. As it happens some of the biggest increases are in the Western Pacific and thereby cause existential issues for low lying island but equally parts of South East Asia and the US south east are more heavily impacted.

Figure 9: Sea level rise regional. Source:NOAA

Ocean currents

As any regular readers will know I am a financial analyst and am no more a scientist than a power engineer. However, in reading and reading about climate change and global warming my attention has been drawn more and more to Ocean currents and the interaction of wind, current and ENSO (El Nino, La Nina). During the last big drought we also heard a lot about the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) and the Southern Annualar Mode (SAM).

Figure 10: Ocean circulation. Source: NASA

Red shows surface currents, and blue shows deep currents. Deep water forms where the sea surface is the densest. The background color shows sea-surface density. (Goddard Space Centre)

It now seems relatively likely that the AMOC circulation is slowing. To quote from a recent article in “The Conversation:”

“Our results show the Atlantic overturning circulation is likely to become a third weaker than it was 70 years ago at 2°C of global warming. This would bring big changes to the climate and ecosystems, including faster warming in the southern hemisphere, harsher winters in Europe, and weakening of the northern hemisphere’s tropical monsoons. Our simulations also show such changes are likely to occur much sooner than others had suspected.”

I took the trouble to read the original academic article and can say there is lots of modelling involved in the forecasts. The authors also cite evidentiary research of what’s been happening.

There are various ways to work out what was going before these measurements began. One technique is based on sediment analyses. These estimates suggest the Atlantic meridional circulation is the weakest it has been for the past millennium, and about 20% weaker since the middle of the 20th century.

I have to note that science about the influence of climate change on AMOC is not settled. Some studies continue to suggest no change. In my view its more likely than not that there will be an impact.

What I am confident of, is its important to get more evidence and theory on AMOC and climate change.

ENSO

It’s well known that for every 1°C of global warming the sky can hold about 7% more moisture. And of course the warmer water evaporates more easily.

So this will clearly lead to more global rain fall. Equally and as pointed out by Robert Rohde in the first episode of Energy Insiders last year, if it doesn’t rain the earth drys out more quickly and more thoroughly.

Some of these things were briefly discussed in two other EnergyInsider episodes, (1 ) with Andy Pitman and (2) Kimberley Reid and what I most remember from those discussion in that one of the drivers of whether it’s rain or drought is the winds. If the winds blow the rain onshore… and if not….

So then, of course, what drives the winds? I doubt I am the first to ask that question. Equally though it’s been customary when discussing an annual climate review to talk about whether it was an El Nino or La Nina year, but perhaps naively I ask myself whether the changing climate will in turn feed back into ENSO behaviour.

Winds drive ocean currents in the upper 100 meters of the ocean’s surface. However, ocean currents also flow thousands of meters below the surface.

These deep-ocean currents are driven by differences in the water’s density, which is controlled by temperature (thermo) and salinity (haline). This process is known as thermohaline circulation.

In the Earth’s polar regions ocean water gets very cold, forming sea ice. As a consequence the surrounding seawater gets saltier, because when sea ice forms, the salt is left behind. As the seawater gets saltier, its density increases, and it starts to sink.

Surface water is pulled in to replace the sinking water, which in turn eventually becomes cold and salty enough to sink. This initiates the deep-ocean currents driving the global conveyer belt.

It turns out there is an entire book devoted to the impact of climate change on ENSO. At the time the book was published (in 2020) the summary was:

“Extreme El Niño and La Niña events may increase in frequency from about one every 20 years to one every 10 years by the end of the 21st century under aggressive greenhouse gas emission scenarios,” McPhaden said. “The strongest events may also become even stronger than they are today.”

In a warming climate, rainfall extremes are projected to shift eastward along the equator in the Pacific Ocean during El Niño events and westward during extreme La Niña events. Less clear is the potential evolution of rainfall patterns in the mid-latitudes, but extremes may be more pronounced if strong El Niños and La Niñas increase in frequency and amplitude.

Discussion on ocean related matters

Australia’s weather is heavily impacted by what’s going on in the surrounding oceans. Australia’s population mostly lives by the coast. El Nino and La Nina have been major features in our land of drought and flood since I was a teenager in the 1960s. Inland agriculture one of the largest sources of export revenue for Australia is obviously heavily impacted by drought and flood.

Our Pacific neighbours are even more threatened by rising sea waters. Since the greater part of sea level rise is from ice melt Australia and its Pacific neighbours need to be concerned about glacier and antarctic ice loss.

In general, global warming can be expected to have more negative impacts on populations less capable of adapting. Australia can adapt but global inequality produces pressure just like any other physical force.

In general it seems to me that from the oceans we can expect marine heatwaves, likely more coastal and on occasion inland rain, and equally in some regions faster and more intense droughts. Coral bleaching hardly needs discussing.

The overall view is that in the past few years across a range of indicators there is evidence of acceleration in impacts. Presumably, like a giant battery, all that energy that has gone into the ocean will have to be released and this is entirely a guess that can’t happen until the carbon forcing is reduced and the ocean heat can escape into the atmosphere.

Notwithstanding that there is a reasonable possibility of global carbon emissions peaking over the next few years and then declining, it seems nearly as likely that climate impacts could get quite a bit worse before they get better.

Global Land and Sea Average Anomaly

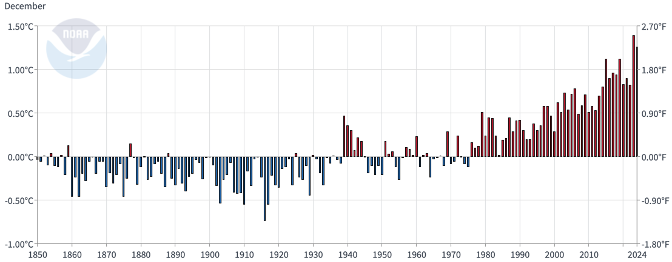

Broadly, it’s been 475 months since we have a monthly temperature that was below the 20th century average for that month. That’s pretty much 40 years. If you are under 40 you have never experienced a temperature colder than the average for that month in the 20th century. I do my own chart of the monthly anomaly but perhaps NOAA does it better.

Figure 11: Global surface temp change. Source: NOAA

Atmospheric carbon concentrations and annual emissions by source

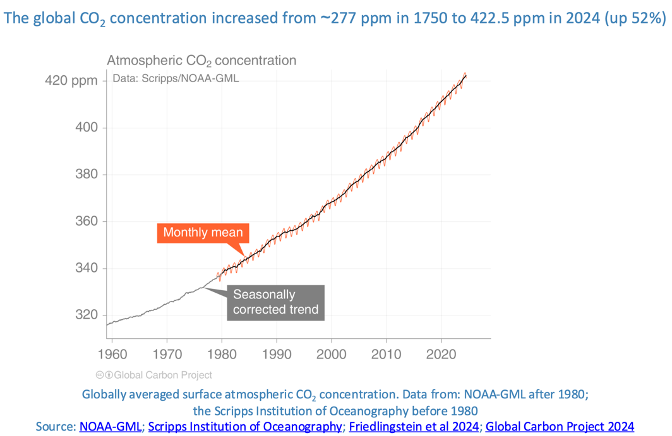

As a reminder theory predicts that as the atmospheric CO2 increases so will the global surface temperature. And that’s what’s happened.

Figure 12: Atmospheric CO2, Source: Carbon Budget

Overall global emissions are about 37.4 Gt in 2024 barely up on 2023.

Figure 13: Global annual emissions. Source: Carbon budget

There are many ways to slice and dice emissions, by country by fuel, per person/country or cumulative. In terms of how to change it though there are only two relevant things, which countries and which fuels. At the margin that’s where you get the biggest bang for the buck in changing things.

Coal remains the biggest fossil source, but gas has gone from a minor share to 21% of annual emissions and gas emissions are now not much below where coal was in 2000 (before China took off).

And by country. It’s clear that China investing in coal generation is what really took things over the top. However, much of what China used the electricity for is exported. In the end it’s a global problem but China has the biggest key.

Figure 14: Emissions by country. Source: Carbon Budget.