Queensland network operator Ergon Energy last week said it would likely encourage some of its customers to go off-grid, because the cost of the network was so high in regional areas that localised renewable energy and battery storage would provide a cheaper option.

While home owners in regional locations often make a choice to go off-grid, particularly those who have to pay a high connection fee for new homes, it is becoming increasingly clear that taking some towns and villages off the grid may also be a better solution.

That possibility has even been raised by the network owners themselves. They face the choice of having to either upgrade extended networks of poles and wires, or help the local community to cut the wire altogether, or at least reduce its size. In South Australia, the local network owner says it would make sense for many communities to look after their own energy needs – perhaps with a “thin” connection as an emergency back-up.

Nic Jacobson, a renewable energy engineer with consulting group IT Power, says it is clear that many communities are already considering their options, and the falling cost of battery storage is making this possible.

He notes that communities in the Northern Rivers region of NSW are looking at creating community-owned retailers, which could conceivably include owning the poles and wires. The city of Lismore, for instance, has already declared a goal to be zero net energy within a decade.

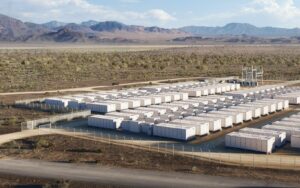

Ergon Energy, meanwhile, says it may install “hundreds” of battery storage units across its network – so avoiding costly upgrades of poles and wires that have few customers. As the cost of battery storage falls, and many think that will happen quickly in a short time, then battery storage may be able to replace the wires altogether.

But how does a community go off-grid, and which communities could do so? The first step is probably for some more cost reflective pricing to be taken into considerations for upgrades and the like. At the moment, Community Service Obligations that guarantee regional users pay the same price as those in the city, is erecting a subsidized block against new technologies. Incentives need to be built into the system to encourage the cheapest option.

Jacobson says the key for any community is to have the community itself on-side with the idea. New entities will need to be created to act as a retailer (and going off-grid means no competition), and to own the network.

The most economic sense is for those communities on the fringe of grids, where customer density is low, and the network delivery costs the highest.

Jacobson pointed to a community on the west coast of the Eyre Peninsula in South Australia, where a single line network 150kms long served just 40 connections.

“This is a good opportunity for a community to take charge of its own energy supply,” he told the All Energy conference last week.

Jacobsen suggests that a co-operative arrangements, and a mixture of solar and wind – or even biomass and wave energy – could create a series of distributed energy sources, shared supply, and the creation of their own mini grid. The blue dots above represent the stand alone power supplies (SAPS) and how they would be distributed around this network.

Country town already do this. Coober Pedy (pictured) in the state’s north runs its own grid, albeit powered by diesel.

Country town already do this. Coober Pedy (pictured) in the state’s north runs its own grid, albeit powered by diesel.

The Australian Renewable Energy Agency is investing $18.5 million to help install a hybrid system solar, wind and storage system that will take the outback town to 70 per cent renewables. Mt Isa in Queensland has its own grid, albeit powered mostly by gas.

For towns such as those relying on “thin connections”, having a mini grid would actually increase reliability and the quality of power. They would no longer be restricted in the amount they could consume.

And it would bring jobs into communities, that would help increase the sustainability of the community at large – particularly in regional towns that are suffering economic downturns.

The biggest issue may be in buying back the network. It is likely that the current owner will want the wires bought back to the point of supply – and there is a question of who will take over decommissioning.

The biggest gap is in the regulation – Jacobson says that current rules do not cover the transition from on grid to off grid. The rules are focused entirely on expanding networks and adding connections.

Still, he says network operators should be on-side with the idea. They can still be involved in supplying the cost of wires and poles within the mini-grid – it will just be part of their non-regulated business, rather than the regulated one.