As world leaders meet in Glasgow for critical climate talks, they have been given a stark reminder of the lowest cost alternatives to achieve the full decarbonised grid that science says is required of major economies by the middle of next decade, at the latest.

Investment bank Lazard has released the 15th edition of its highly regarded Levelised Cost of Energy Analysis and it reinforces what is pretty much already known: Wind and solar are by far the cheapest forms of electricity generation, storage costs are falling, and now hydrogen is part of the equation.

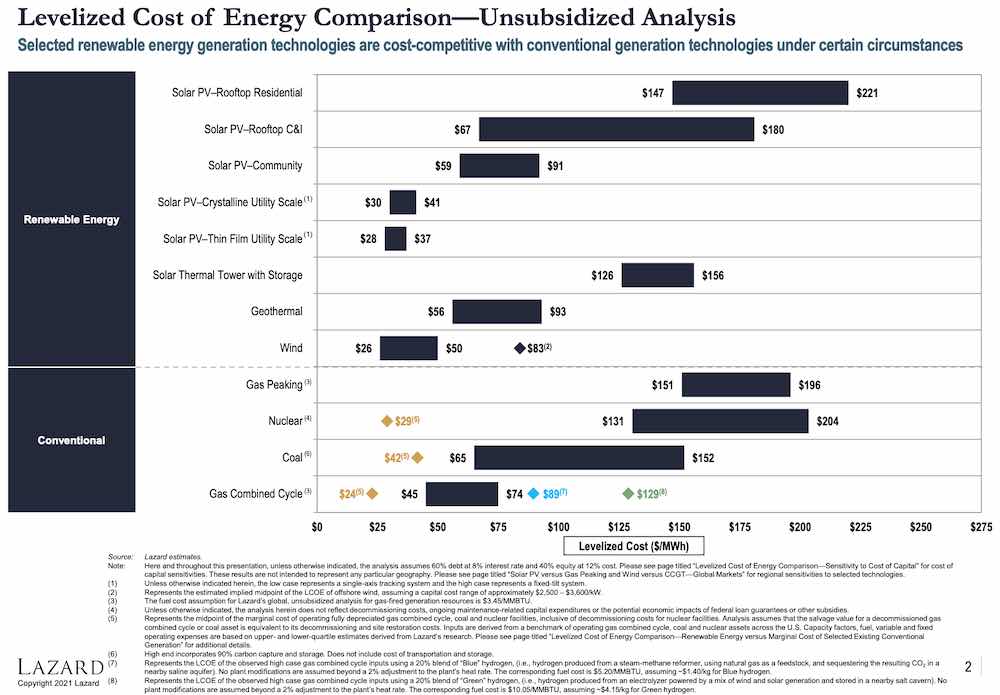

The best illustration of the cost difference between the various technologies is this following table, which shows the various energy supply sources and their sensitivity to the cost of capital.

All technologies are affected in some way, but wind and solar, which are easily the cheapest form of generation, actually increase their advantage as the cost of capital increases. In all cases, they are five times cheaper than nuclear. Even storage and network costs don’t come close to making up the difference.

The advantage of wind and solar is so vast that they are competitive with just the “marginal costs” of coal, gas and nuclear. These marginal costs are the cost of production such as fuel and maintenance.

It goes to show that wind and solar don’t just beat new installations, they are by and large competitive with even existing coal, gas and nuclear plants, even after the huge capital costs of those plants have been amortised.

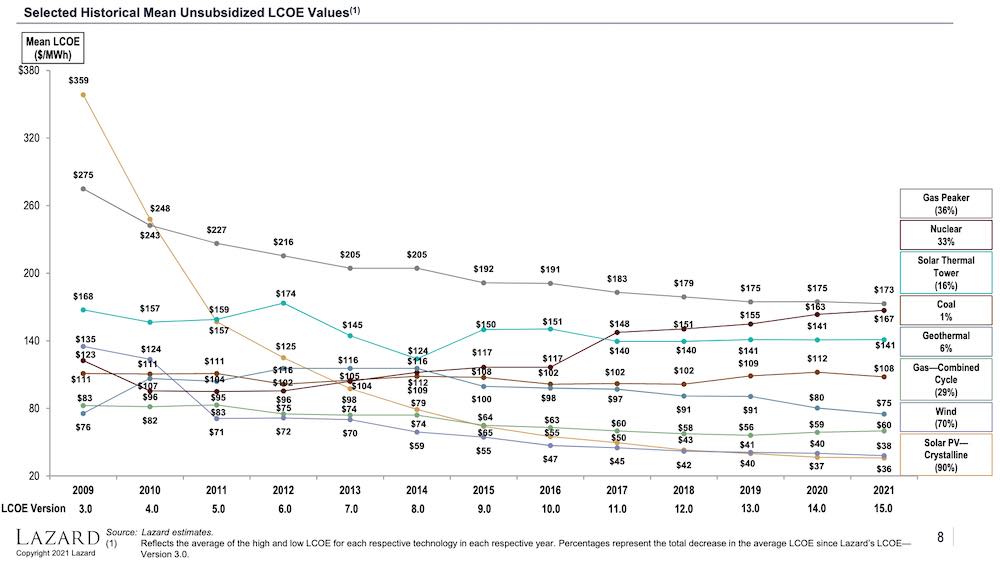

This next graph illustrates the cost of solar and wind technologies versus gas peaking and combine cycle technologies. Wind and solar win on both counts, although the cost of storage is not included.

But what is interesting is that it shows that Australia has some of the most cost competitive wind and solar resources compared to other countries. It’s pipped only by the US among the cost estimates for major economies.

And while the report notes that, without storage, solar and wind lack the dispatch characteristics of gas plants, Lazard’s 7th Levelised Cost of Storage report, also released this week, puts the unsubsidised cost of wholesale PV and storage (50MW/200MWh) at between $US85-$US158, putting it in the ballpark, already, with new peaking gas. This explains why solar and batteries are beating gas plants in US tenders.

And while this further undermines the federal government’s big bet on gas, the Coalition’s recently announced stretch target for “ultra-low-cost” solar production at less than $15 per megawatt-hour, or 1.5 cents per kilowatt-hour, is supported by the continued fall in the costs of solar noted by Lazard.

Lazard puts the current unsubsidised cost of solar PV at $US30-41/MWh and notes in its report that, while rates of decline in the LCOE for onshore wind and utility-scale solar have slowed in recent years, the pace of decline for solar continues to outpace onshore wind.

Having charted a stunning drop in LCOE of 90% since 2009, utility-scale solar has delivered five-year compound annual declines of 8% in the average LCOE, compared to 4% for onshore wind. Nuclear, meanwhile, has seen a 33% increase in LCOE since 2009.

On energy storage, Lazard finds that year-on-year changes in the cost of storage are mixed across use cases and technologies, driven in part by the confluence of emerging supply chain constraints and shifting preferences in battery chemistry.

The LCOS report also notes that hybrid applications, such as solar or wind paired with storage, are becoming increasingly valuable and widespread as grid operators begin adopting methodologies to value resources.

Finally, Lazard also published its 2nd Levelised Cost of Hydrogen (LCOH 2.0) assessment, which shows that cost is still largely dependent on the price and availability of the energy resources required to produce it.

Currently, Lazard says the LCOH remains more expensive than the fuels it would substitute, with the key drivers to hydrogen’s levelised cost being cost of electricity, capital expenditures for production equipment and utilisation of the electrolyser.

The report also notes that the applications most readily suited to hydrogen conversion – and most likely to transition towards hydrogen most quickly – included those requiring minimal transport, conversion or storage.

“Our three studies together document the continued acceleration of the energy transition,” said George Bilicic, the vice chair and global head of Lazard’s Power, Energy & Infrastructure Group.

“We’re also seeing that the transition will not be dominated by any one solution — rather a new ‘all of the above’ approach, which includes renewable energy, storage, hydrogen and other solutions, will be key to effecting the permanent shift to increased energy efficiency and sustainability.”