As countries and companies continue a widespread global shift away from denial and inaction on climate, a new question is coming to dominate discourse: What’s the pathway?

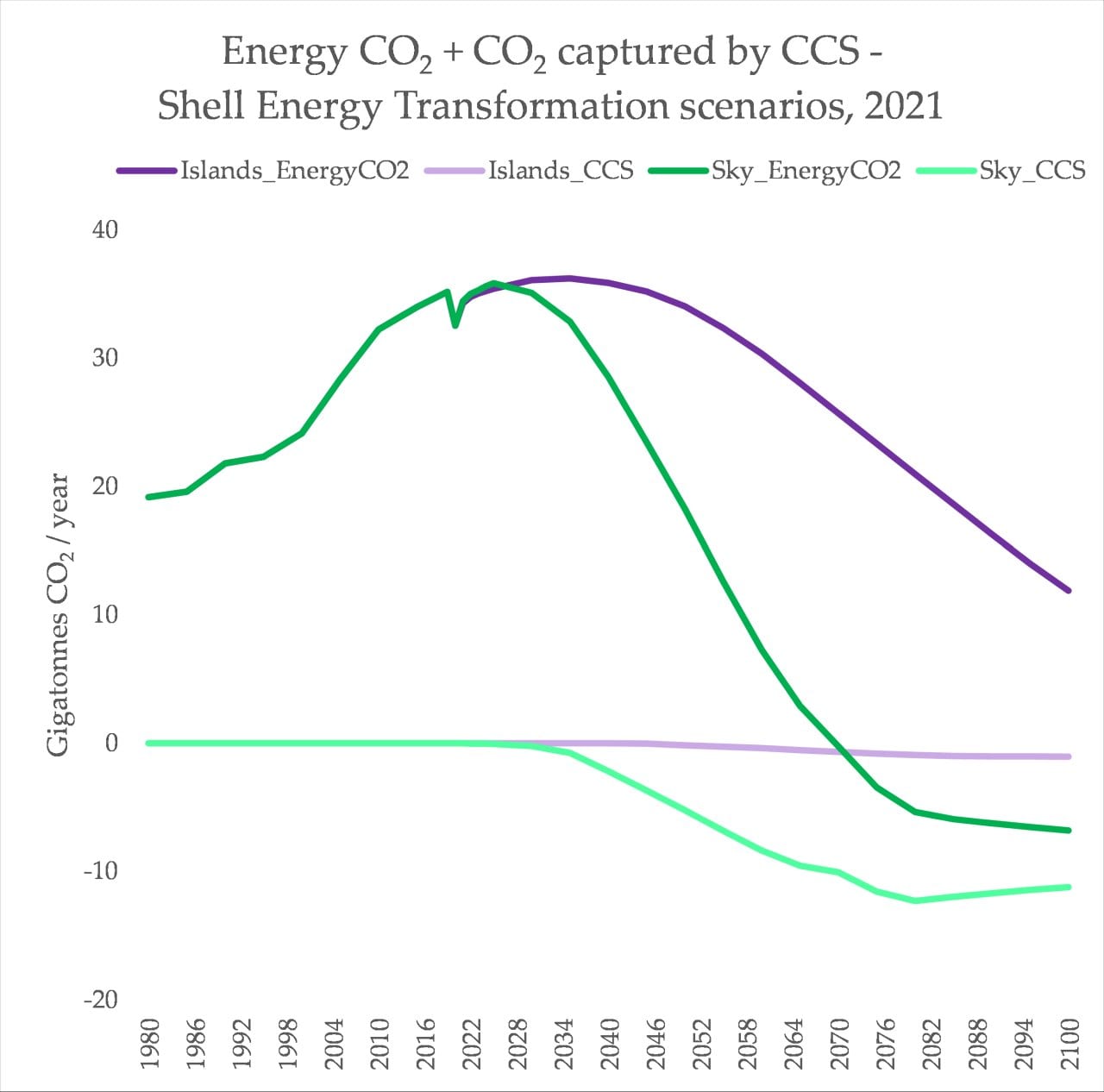

Today, fossil fuel companies are largely answering that question in a consistent way: continue burning coal, oil and gas, and assume that some massive advancements in carbon capture technology will soak those emissions up in the future. Shell, one of the world’s biggest fossil fuel companies and heavily reliant on selling oil and gas, was criticised heavily for this in its 2019 ‘Sky scenarios’ document. Carbon Brief wrote of that document,

“Even this lower-end deployment of CCS would be a huge challenge: Shell suggests it would need a new industry at least as large as the current global fleet of coal-fired power stations….This is despite the risks of relying on what remains a relatively untested range of technologies and approaches – and the moral hazard of assuming negative emissions will be possible”.

Promises of carbon capture filling in for plans to reduce fossil fuel usage and deploy renewable replacements is, on reading their new report, still a problem, if Shell’s update on their energy transformation scenarios is anything to go by. For the first time, the company’s various visions of the future include a target of limiting average global warming to 1.5°C, an ambition that entails even greater reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. There is no ambiguity in this report: Shell fully accepts the need to eventually ditch fossil fuels.

“A healthy planet requires a transition of the energy system from one that relies primarily on fossil fuels to one that increasingly uses sustainable sources of energy to achieve net-zero emissions” – Shell’s Energy Transformation Scenarios

The report digs into three scenarios:

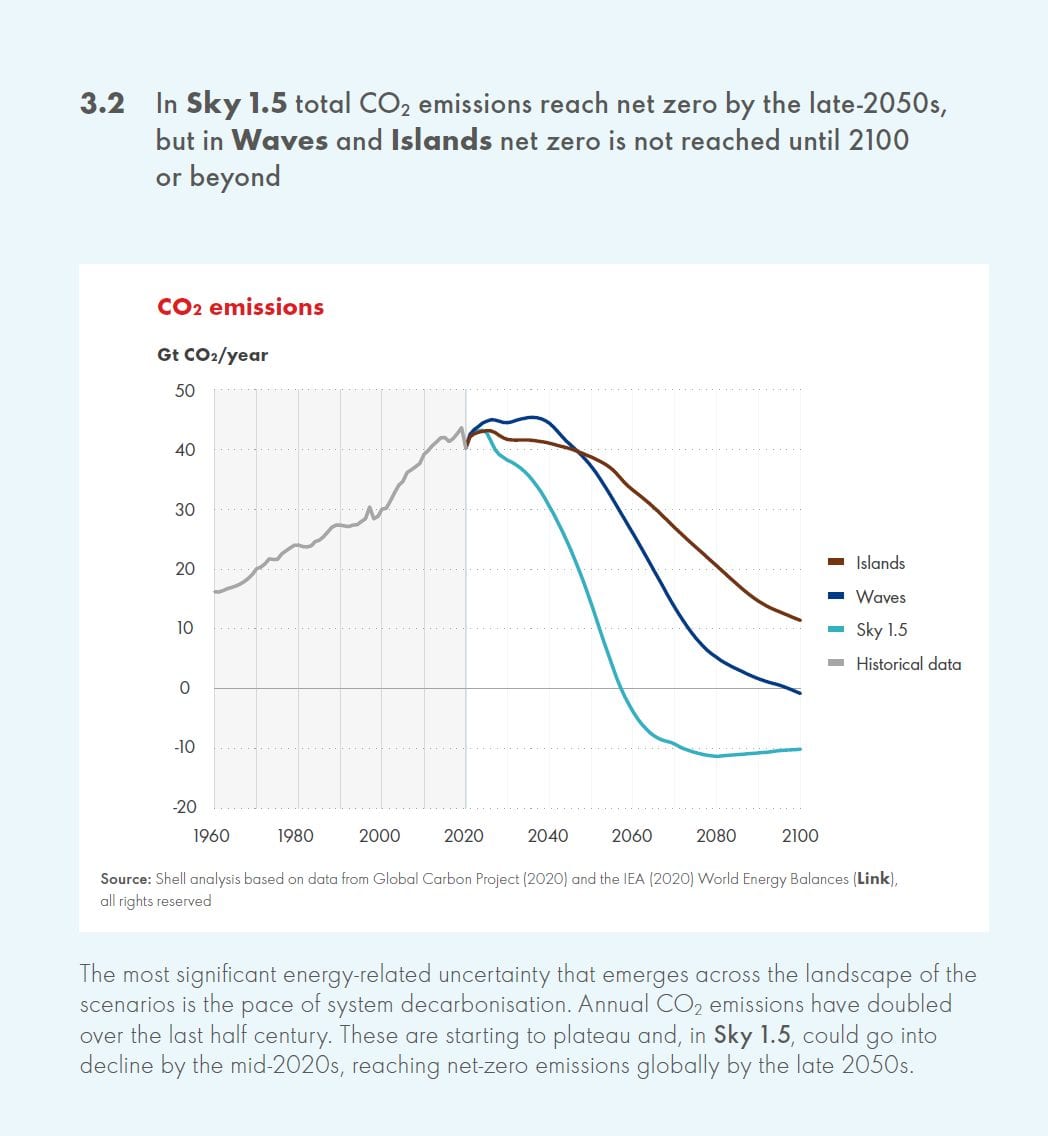

- Waves, in which the net zero by 2050 goal is just met, but very late and in haste (2.4°C warming by 2100);

- Islands, in which the 2050 goal is missed, due to slow and late action (2.5°C warming by 2100);

- Sky 1.5, in which rapid, early action results in the goals of the Paris agreement being met.

In ‘Sky’, 50% of the world’s electricity is renewable by 2043, 50% of passenger cars are electric by 2046 and 20% of aviation is hydrogen by 2095. In all three scenarios, wind and solar perform most electricity sector decarbonisation. But outside of electricity, Shell’s unique stamp on its visions starts to emerge.

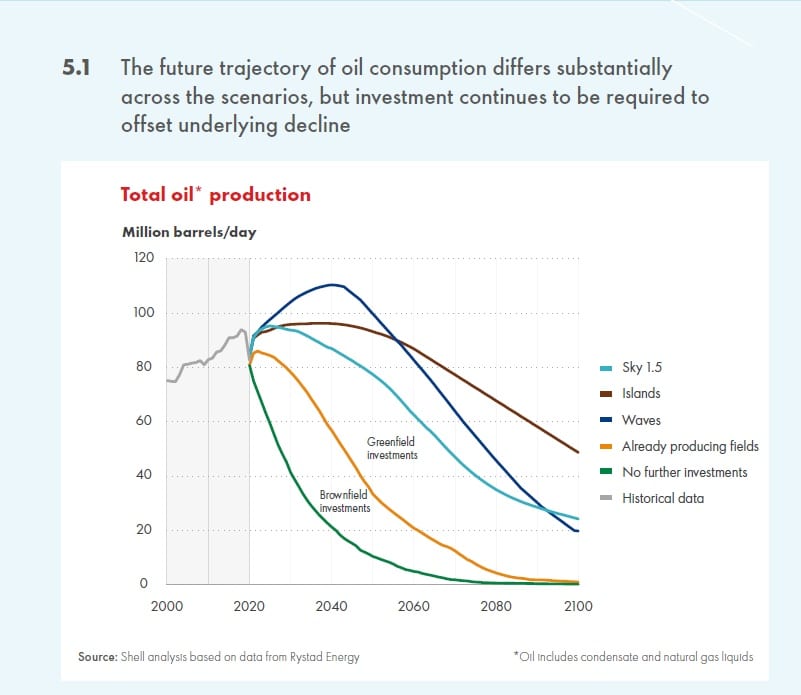

Significantly, the company is strongly insistent on the need for continued extraction and burning of oil and gas, in the coming decades, even in its 1.5°C scenarios:

“Given the ongoing need for energy-dense liquid fuels, the world will continue to need oil throughout the century. The level of demand, however, will decrease significantly depending on the different paces of energy transition in the different scenarios, particularly in the transport sector. Investments in producing and new oil fields are still required in all scenarios. Fields that are currently producing will not able to meet long-term demand, even in the low-demand Sky 1.5 scenario”

They’re bullish on gas too, of course. “Natural gas is a readily available alternative to coal in power generation and plays an important role in decarbonising the energy system.

As a result, investments in gas supply and midstream transport infrastructure initially increase in all three scenarios.”

This, despite the rising tide of opposition to gas-fired power from communities, investors and energy system operators, all fully aware that leapfrogging gas and going straight to zero affords the best outcomes for reliability, cost and emissions.

This is where the imagination of Shell’s modellers hits a brick wall: a reduction in the operation of their business within the next few decades is essentially unthinkable, and unmodeled. There is plenty of optimism about renewables, energy efficiency and electric vehicles, but there is also optimism about the continuation of their core business, to be cancelled out – eventually – through the operation of carbon removal.

https://twitter.com/GlobalEcoGuy/status/1359034277883740160

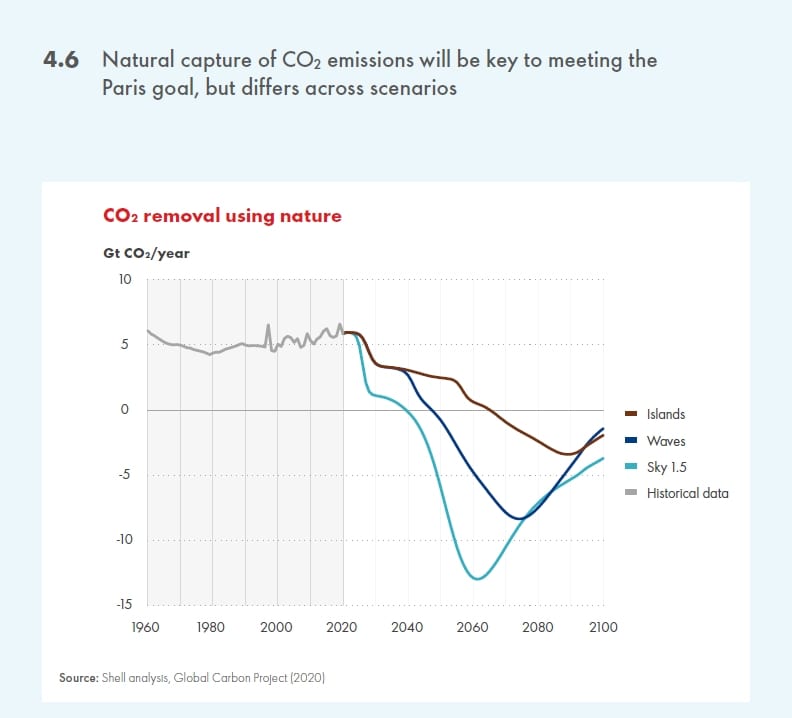

Once emitted into the sky, carbon can be removed through two ways – by creating new organisms that suck up carbon, like trees and grasses, or through technologies that literally suck it out, like direct air capture (DAC). Historically, promises to scale these up to allow for the continued burning of fossil fuels are catastrophic failures. In addition to total failures of scale:

“Several afforestation and REDD+ projects, for example, have been accompanied by instances of dispossession and human rights abuse. In other cases, vulnerable and politically marginalised communities end up carrying the risks if projects fail” – Carbon Brief