Predicting the arrival of solar energy for electricity that is as cheap as local electricity prices is actually harder than predicting the sunrise. But UCS’s new solar infographic tells this exciting crossover point is right in front of millions of homeowners across the country.

What’s going on up on the roof?

For more than 120 years, homes and businesses have been buying electricity. Now rooftop solar electricity production is changing the way hundreds of thousands of homeowners get energy. Most have added solar panels because this makes money, and that motivation will keep growing and spreading.

Small-scale solar photovoltaic (PV) systems on rooftops have suddenly become the most commonly built, most numerous electric generators, with individuals making decisions based on the cost of the solar panels and the price of their local electric utility.

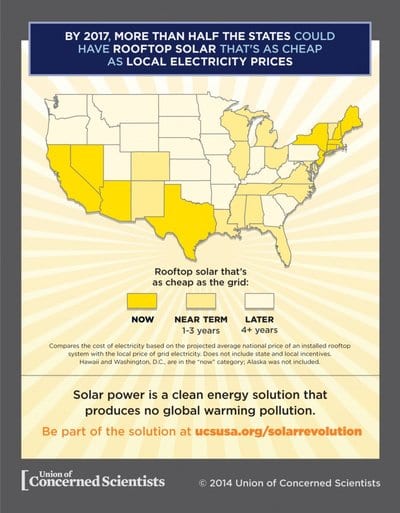

Over half the states could have rooftop solar that’s as cheap as local electricity prices by 2017

UCS estimates that with rapid declines in the cost of panels and installations, homes in 11 states plus the District of Columbia can use a federal tax credit and financing to make electricity cheaper than they buy it. Seventeen more states are within three years of this tipping point. This map shows where.

This is big news! Some say it is the end of the old ways, a revolution.

How do we reach that conclusion? We start with two National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) analyses of break-even for an investment in PV (solar photovoltaic) panels compared with paying the residential rate for electricity. We picked through the NREL studies as we were producing our own update on the rise of solar energy. In their analysis, NREL assessed the available sunshine, projected current and future local electricity prices escalating 0.5% per year, and included financing and federal tax incentives to determine what the cost of solar (in dollars per watt) would need to be to reach break-even.

What was really missing from these NREL studies is a projection of when the break-even point is likely to be reached. Not faulting the lab, just saying that when UCS compared the NREL numbers on break-even costs and other organizations projections of prices, this all became more clear. And much more interesting. Now anyone can look at the map and see there are going to be some changes coming.

NREL’s analysis (and therefore ours) is conservative in some important ways:

- No state or local incentives are used. Including existing state tax incentives available in 45 states, or other local support for solar generation would lower the break-even cost for a residential PV system (net present value).

- Some utilities have an optional time-of-use rate structure that also would improve the economics of residential solar. The benefits of this can be seen in this analysis.

- Also not included in our take on the NREL numbers is a price on carbon, which would recognize a value of avoiding emissions.

Deutsche Bank and NRG have come to very similar conclusions with their own analyses, while others like Citigroup predict continued declines in the cost of solar panels, global demand, and inevitable price parity.

How soon can you get solar?

New energy supplies are often known long before they become practical and economical. Wind power, nuclear power, and shale gas all had been identified as potential energy supplies but were considered too expensive. Wind power and shale gas have come way down in price. Now solar is making its move. And rooftop solar is crossing the threshold, and a solar boom is underway.

If you are interested in getting solar panels on your roof, ask for a quote from a solar firm. Since our map did not include state and local incentives that can accelerate the economics, you may get an even better answer. Keep in mind that the NREL assumption about how energy prices will change is only an assumption.

Unlike most energy supply decisions, the choice of rooftop solar is within your control. If you want to adjust your economics to recognize carbon savings, you can do that too, with this energy choice. There is so much that changes when solar becomes cost-effective. This is just getting started.

Source: UCSUSA. Reproduced with permission.