Australia has been consistently compared to New Zealand, when it comes to climate. This happens in two contexts: the first, to make Australia look bad, and the second, to make it look good.

The reason this dual-function comparison exists is because New Zealand’s climate ambitions are so mixed and its emissions problems are so different to those of Australia.

A nice example would be the protestations recently made by Australia’s leader of the Nationals, Michael McCormack, to follow New Zealand’s lead in “exempting” emissions related to farming – that is, ‘biogenic” methane produced by animals – from any net zero plan.

Randomly slicing off huge chunks of emissions from targets certainly seems like something that would appeal to Australia’s conservative parties. Agriculture isn’t really “excluded” in NZ – it just has a weaker target, for a reduction between 24% to 47% by 2050.

But by the same virtue, New Zealand’s non-agriculture targets are far better. It intends to reach net-zero emissions for other sectors by 2050, a goal that is enshrined in law (the ‘Zero Carbon Act’). It has a 30% by 2030 climate target, slightly better than Australia’s 26%. These are all steps that have been shunned by Australia’s government.

This week, an independent body set up to supply advice to the New Zealand government (the Climate Commission) produced a massive document that justifies a strengthening of New Zealand’s next three five-year carbon budgets, particularly shifting ambition closer in time. Between 2022 and 2025, emissions must fall from 2019 levels by 7%. For 2026-2030, 20% and for 2013-2035, 35%.

New Zealand’s chequered climate history

The report is explicit about New Zealand’s failures to take substantial action on climate in the past. “While the targets [of successive governments] have changed, they all shared the same short-term focus on planting trees and purchasing offshore mitigation, rather than what was necessary to achieve actual emissions reductions at source”, write the authors.

“Our analysis shows that current government policies do not put Aotearoa on track to meet the Commission’s recommended emissions budgets or the 2050 targets. Achieving the emissions reductions needed to get to 2050 will require our elected officials to move fast to implement a comprehensive plan.”

The components of the plan are numerous, detailed and significant. The sizes of herds needs to drop by 10-15%, combustion engine imports and household gas connections need to stop, and the share of EVs in new car sales needs to rise to 50% by 2030.

But the track record is poor – Marc Daalder at Newsroom has covered New Zealand’s climate and energy policies in detail and he elaborates on New Zealand’s historical failures here.

“While other countries have managed to reduce emissions in the past three decades, New Zealand’s have only grown. In fact, we hold the dubious honour of registering the second greatest increase in net emissions since 1990 of any industrialised nation, beat out only by Turkey,” he wrote.

Greenpeace has called out the Climate Commission’s suggestions, saying that they give far too much leeway to the country’s agricultural industry.

“Intensive dairying is to New Zealand what coal is to Australia and tar sands are to Canada. If this government is serious about tackling the climate crisis, it must do what we already know will cut climate pollution from intensive dairying: phase out synthetic nitrogen fertiliser, substantially reduce stocking rates, and support farmers to shift to regenerative organic farming”, said Amanda Larsson, from the group. And a group of high-powered lawyers are preparing to challenge the report.

@ClimateCommNZ's final advice is disappointing 😥 The proposed budgets still do not meet legal requirements. We are considering judicial review.

We fully support @ClimateCommNZ's obejctives and all steps to reduce emissions. However, we cannot support the proposed budgets.

— Lawyers for Climate Action NZ 🌏 (@law4climateNZ) June 9, 2021

New Zealand’s fossil fuel lobby wasn’t too happy about it either, though their gripes were quite specific. “We’re also disappointed at the Commission’s use of the term ‘fossil gas’. It’s highly unprofessional and undermines their credibility and integrity. No need given ‘natural gas’ is the official term, widely understood and clearly different from hydrogen and bio-gases,” said Energy Resources Aotearoa. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand welcomed the report.

A power sector change driven by electrification

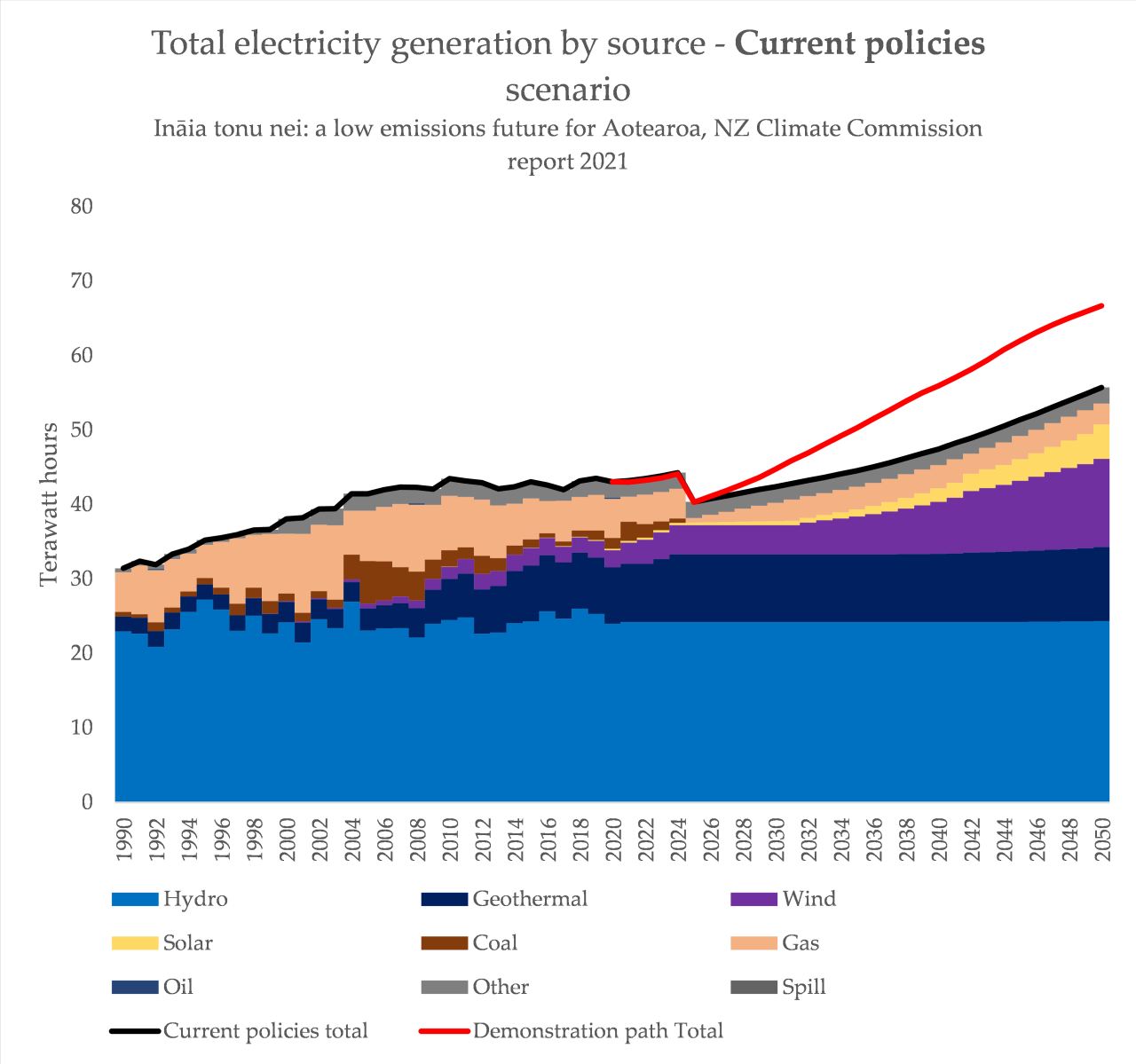

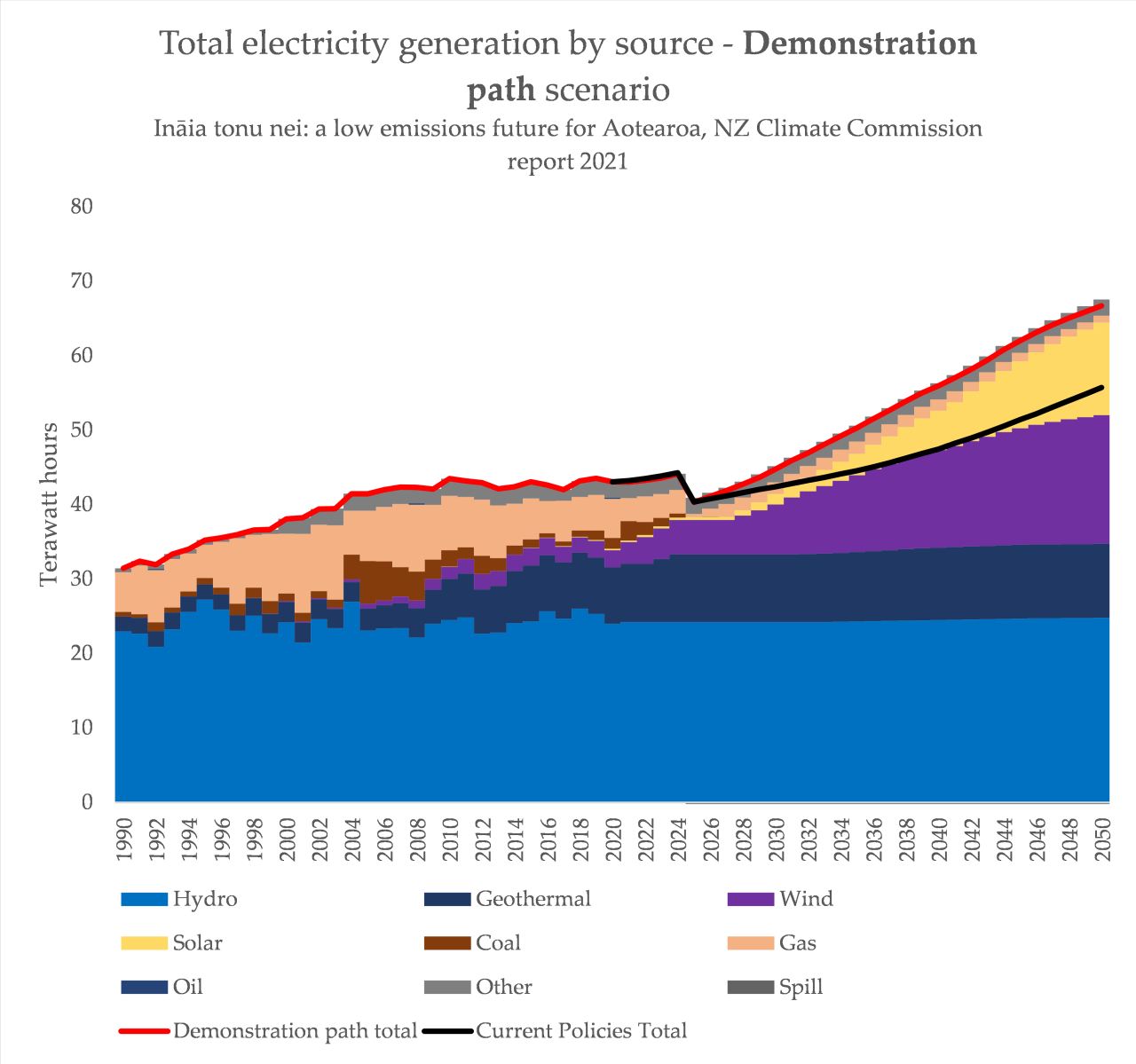

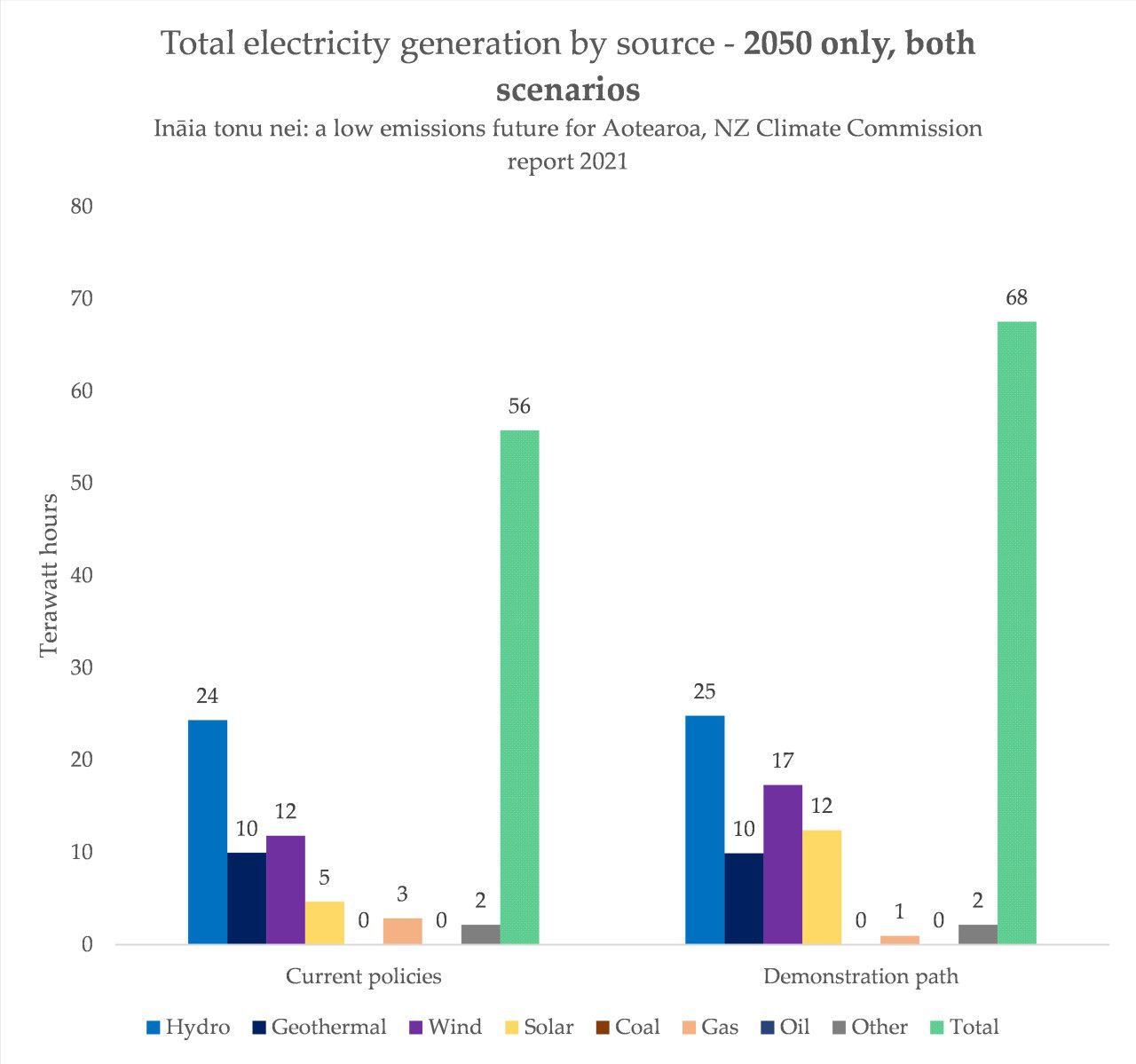

The report also supplies data on the country’s electricity sector. Though it is not a large proportion of the country’s total emissions (9% of energy-related emissions in 2020), it undergoes a notable shift to meet new demand from electrified transport, homes and industry in the scenarios published (the drop in total generation in 2024 is due to the forecasted closure of the Tiwai Point Aluminium Smelter). The ‘Current policies’ pathway projects the trajectory based on the country’s existing legislation, and the ‘demonstration path’ provides an illustration of how to achieve the suggested targets:

Notably, electricity demand is about 20% higher, there is 2.7x as much solar, 1.4x as much wind and only a third of the gas generation:

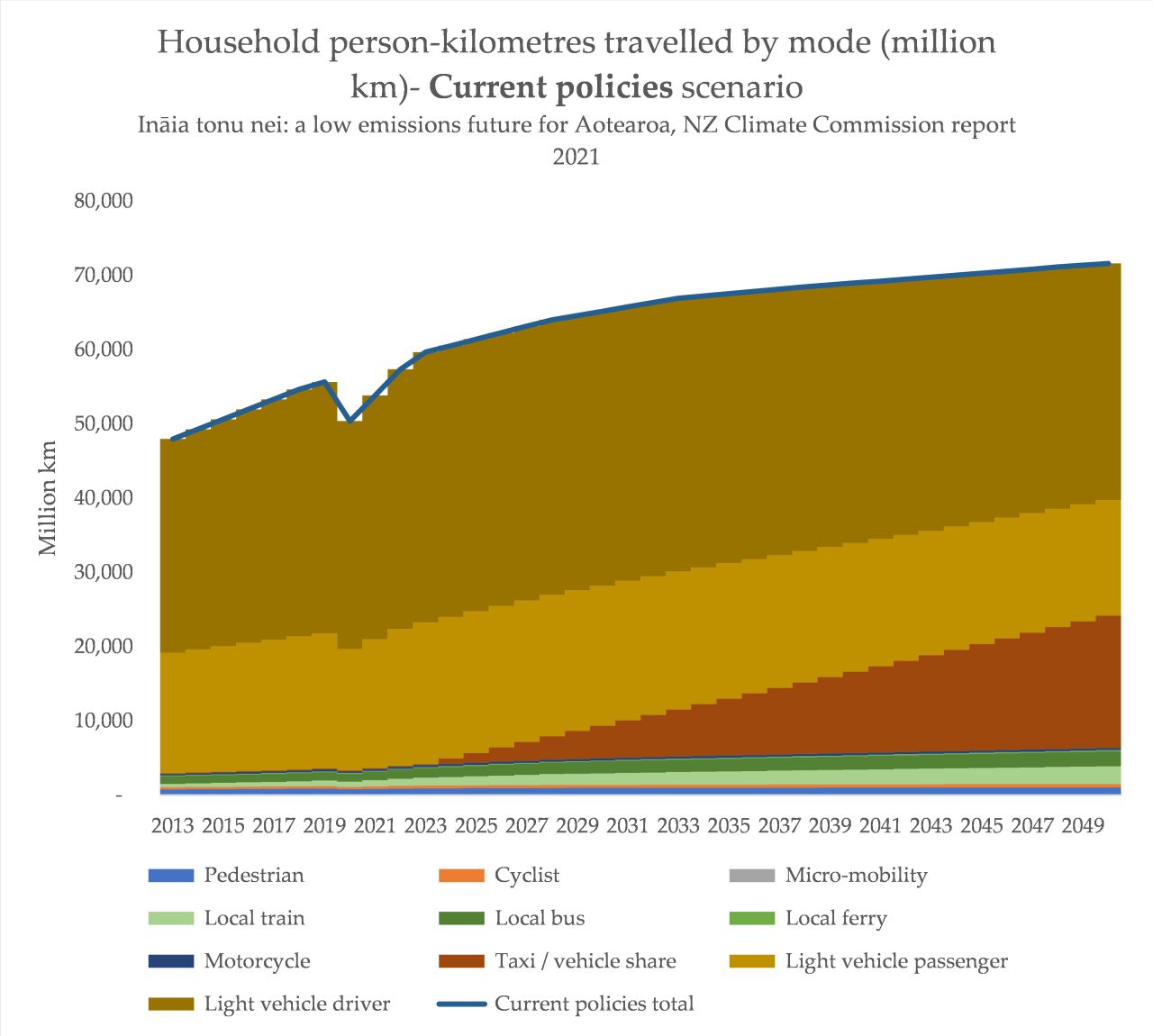

And modes of transport diversify notably, away from light vehicles and towards car sharing, cycling, micro-mobility and public transport:

Much of how this plays out depends on the government’s policy response, and how they walk the fine line between various vested interests.

But in comparison to Australia, the fact that this conversation – and these types of analyses and expert commentary – even happen is far beyond anything in Australia’s governmental climate discourse.

And, of course, digging up and exporting fossil fuels is both emissions intensive at the production point and the use point; whereas agriculture’s products – dairy, meat, etc – are emissions intensive only at the production point.