As debate resumes in federal parliament this week over where new coal and gas projects should stand in Australia’s emissions reduction legislation, science has delivered its own crystal clear verdict on the matter:

Forget new coal and gas; the emissions from existing fossil fuel projects, alone, could be enough to blow the remaining global carbon budget by the end of the decade if they carry on unabated.

Rather, with the huge – and cheap and ready – contributions that renewables, energy efficiency and electrification can make to reductions in both carbon and methane emissions, we should be going full steam ahead in the other direction.

And yet, we are not.

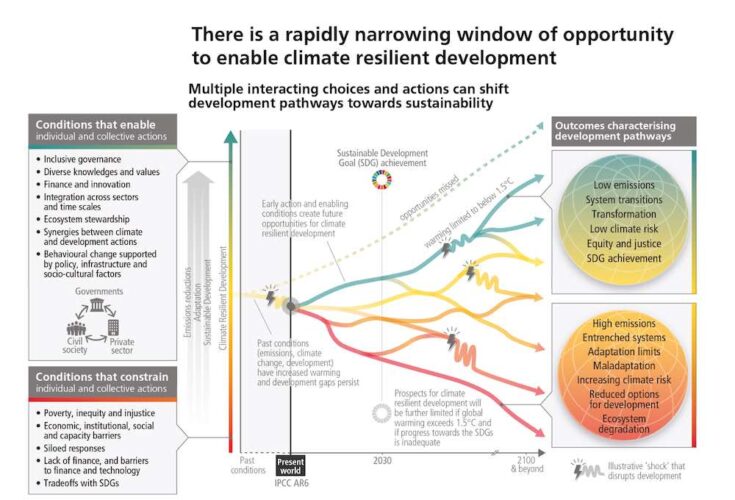

According to the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, published on Monday night (Australian time), the world is still falling drastically short of the sort of action needed to limit global warming to 1.5°C.

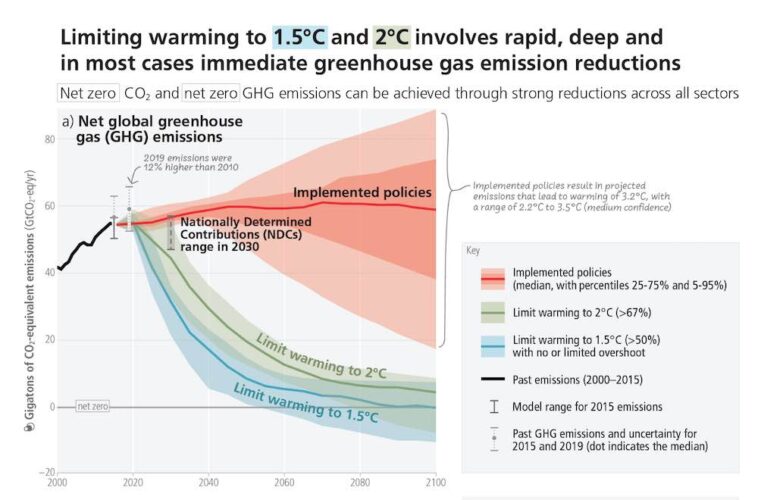

The IPCC Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report warns that if annual CO2 emissions between 2020-2030 stay the same as in 2019, the world will exhaust most of the remaining carbon budget for 1.5°C in that time.

For the energy sector, more specifically, the report finds that projected CO2 emissions from existing coal and gas infrastructure, alone, without additional abatement would exceed the remaining carbon budget for 1.5°C.

“IPCC scientists don’t mince words on the biggest threat to humanity: continuing to burn fossil fuels,” says Ani Dasgupta, president and CEO of the World Resources Institute.

“Despite the rapid growth of renewable energy, fossil fuels still account for over 80% of the world’s energy and over 75% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

“Without a radical shift away from fossil fuels over the next few years, the world is certain to blow past the 1.5°C goal,” Dasgupta says.

“The IPCC makes plain that continuing to build new unabated fossil fuel power plants would seal that fate.”

Currently the IPCC estimates that global emissions in 2030 implied by nationally determined contributions make it likely warming will exceed 1.5°C during the 21st century and make it harder to limit warming below 2°C.

The report, compiled by almost 300 scientists across 67 countries, reminds us once again why this is a very bad outcome, particularly for the up to 3.6 billion people around the globe already considered to be highly vulnerable to climate change.

“It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land,” the report says.

“Climate change has caused substantial damages, and increasingly irreversible losses, in terrestrial, freshwater, cryospheric, and coastal and open ocean ecosystems,” the IPCC says.

“Hundreds of local losses of species have been driven by increases in the magnitude of heat extremes with mass mortality events recorded on land and in the ocean.

“Impacts on some ecosystems are approaching irreversibility such as the impacts of hydrological changes resulting from the retreat of glaciers, or the changes in some mountain and Arctic ecosystems driven by permafrost thaw.”

The scientists say that the best estimates of the remaining carbon budgets from the beginning of 2020 are 500 GtCO2 for a 50% likelihood of limiting global warming to 1.5°C and 1150 GtCO2 for a 67% likelihood of limiting warming to 2°C.

To stick to the 1.5°C budget, the scientists say, we must target net zero emissions by 2050, with a good deal of the heavy lifting to be done in this decade.

Professor Malte Meinshausen from The University of Melbourne, and a member of the report’s core writing team, says the assessment provides an indication of 60% greenhouse gas emission reductions below 2019 levels by 2035, and for CO2, 65%.

For 2030, the goal is for a 43% reduction in greenhouse gas, 48% for CO2, and for methane, roughly a 30% reduction by 2030.

“The report assesses that the technical opportunity to cut emissions the world over amounts to half, we can halve emissions globally between now and 2030, at incremental costs of less than 100 US dollars per tonne of carbon dioxide,” adds Australian National University’s Frank Jotzo, who is also a member the report’s core writing team.

But there can be no new coal or gas plants, and no more fossil fuel exploration and development carbon bombs.

“The world cannot tolerate one more drop of new oil or gas if we are to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement,” says Anusha Narayanan, global project lead against fossil fuel expansion at Greenpeace US.

“New fossil fuel projects – including drilling into carbon bombs from the US Permian Basin to Northwest Australia – are directly undermining the prospects of a habitable planet.”

On the flip side, the report points out that the energy sector is well placed to do a lot of the heavy lifting that’s so urgently needed, given the right policy support and investment.

“Several mitigation options, notably solar energy, wind energy, electrification of urban systems, urban green infrastructure, energy efficiency, demand-side management …are technically viable, [and] are becoming increasingly cost effective,” the report says.

“Large contributions to emissions reductions with costs less than $US20 tCO2-eq-1 come from solar and wind energy, energy efficiency improvements, and methane emissions reductions (coal mining, oil and gas, waste).

“Climate responsive energy markets, updated design standards on energy assets according to current and projected climate change, smart-grid technologies, robust transmission systems and improved capacity to respond to supply deficits have high feasibility in the medium- to long-term, with mitigation co-benefits.”

For Australia, the IPCC’s latest climate assessment comes as federal parliament resumes debate over Labor’s proposed amendments to the Safeguard Mechanism.

Climate Council director of research Simon Bradshaw says the “unmistakable” central message from the scientists – that the extraction and burning of fossil fuels must stop this decade – must inform decisions on national climate policy.

“If we start giving it our all right now, we can avert the worst of it,” Bradshaw says. “So many solutions are readily available, like solar and wind power, storage, electric appliances and clean transport options. We need to get our skates on.

“This is why it’s important to get the Safeguard Mechanism right,” he adds.

“The era of big polluters trading our future for a quick dollar must now come to an end. Coal, oil and gas needs to be phased out and left behind in the polluting past where they belong, replaced by the clean industries of the future.”

Another key message for gleaned from the IPCC report by the Climate Land Ambition and Rights Alliance (Clara), is that there is no space in the remaining carbon budget for any offsetting.

“It doesn’t matter if the offset calls itself ‘high integrity’ or has the best green certification. It doesn’t even matter if the credit is junk. If the offset excuses ongoing emissions, it contributes to the problem, not the solution,” Clara says.

“The IPCC is quite clear that we need ‘removals’ of CO2; even the fastest and deepest decarbonisation of our energy, transport, and food systems will still result in some residual emissions.

“The IPCC also makes clear that while urgent and important, the amount of CO2 that potentially can be removed (that is, sequestered) in forests and grasslands is extremely limited, and that natural lands deliver meaningful reductions in atmospheric concentrations only in multi-decadal timeframes. Trees need time to grow.

“The IPCC’s most important qualification regarding removals is to limit their use to counter-balancing ‘hard-to-abate’ residual emissions.”