The offshore wind industry, although no doubt a great opportunity, appears to have deeply damaged turbine manufacturers in the short term, partly due to issues in that part of the value chain, and partly due to the industry taking its eyes off the onshore industry.

The turbine industry seemed to lose sight of basic manufacturing principals such as fully amortising development costs, keeping production simple, focusing on repeatability. Perhaps this was partly caused by fear of what the solar industry was going to do to wind.

The wind industry shouldn’t worry. Despite the difficulties with transmission and social license, and the fact that solar costs keep falling; despite all that, the world needs a profitable and large wind industry. Wind and solar are complementary and wind will provide most of the overnight bulk energy the world needs.

Of the companies glanced at in this note, and the note hardly constitutes analysis, I think Vestas and Goldwind both could justify some more investor attention.

I don’t see onshore costs going up from here – in fact, I can see them going down again once turbine manufacturers get back to manufacturing basics.

A number of turbine manufacturers clearly also see grid services – e.g. DC cable – as an industry to get into. And of course maintenance of existing and new wind farms will eventually grow to be a very large business for the industry.

Solar panel manufacturers are now profitable

A few years ago the Chinese solar industry was not very profitable. More recently, reports from, say, Jinko indicate that the industry is doing better.

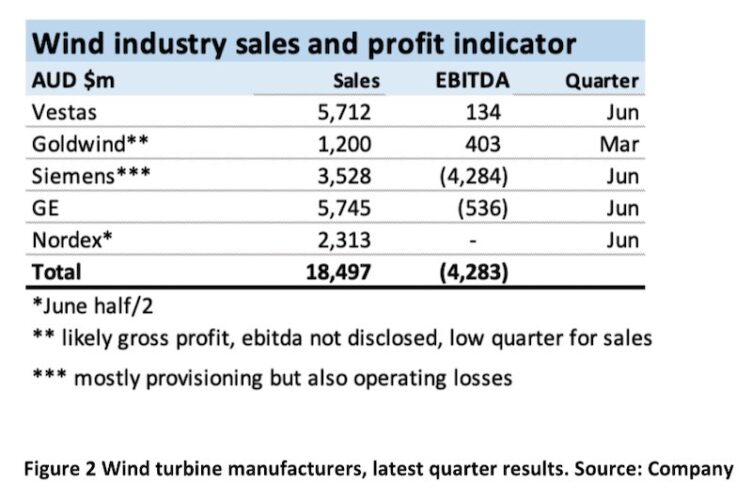

The wind turbine industry is break even, at best

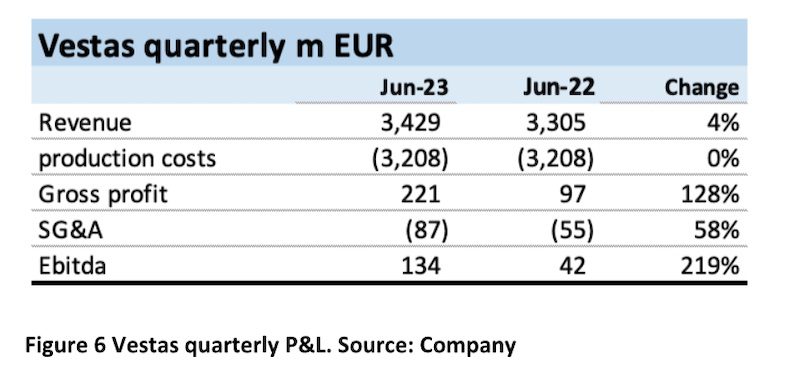

Vestas, the world’s largest wind turbine manufacturer, is losing money at the EBIT level but is doing much better than a year ago, after raising turbine prices 38%.

Nordex is breakeven, GE is losing money both onshore but particularly offshore, and Siemens Gamesa is a full on disaster, saving only that it was the company’s own monitoring systems that picked up the problems. Otherwise no doubt they would eventually be worse.

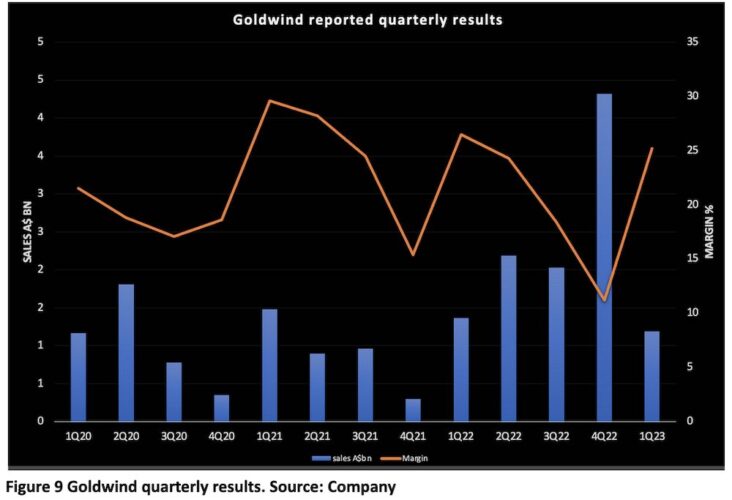

Goldwind’s numbers are from the presentation as no formal quarterly P&L in English was available on the website or reported on Factset.

Of course, one quarter’s numbers are not much of an indicator. But in general they are reasonably indicative, in my opinion.

These manufacturers represent over half world production.

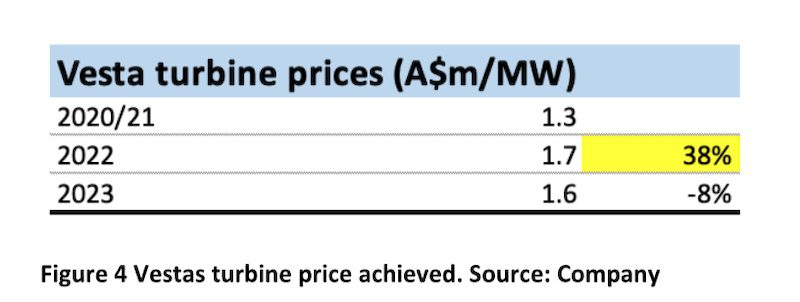

Turbine prices rose 38% but are now stable to declining

Vestas’ achieved price has stabilised for new sales around $A1.6 million per megawatt (that’s before transport to Australia, of course), up from roughly $1.3 million in 2020 and 2021.

Turbine prices are not the only thing to drive the price of wind, even after allowing for the exchange rate. The cost of capital is also a big deal, with every 1% change in the WACC adding, say, 10% to the required price to hit LCOE (long run marginal cost or the price required to justify investment).

Around $75/MWh electricity price needed for new wind farm in Australia

The 10-year swap rate in Australia is around 4.5% and BBB corporates could expect to pay about 1.5% above that. For wind farms, I presently guess a debt cost of 6.5% and an cost of equity of 9%. That gives you an after tax WACC of something like 7%.

In my opinion, that’s about 1.5% above what it was when bond rates were 1% and has raised the required electricity price about $8/MWh, i.e. from, say, $70/MWh to, say, $78/MWh. A couple of years ago when turbine prices were 25% lower we were talking wind PPAs of less than $50/MWh.

Bid prices in China have resumed their downward trend. However, this number does not directly compare with turbine costs or PPA prices. It appears, and I may well be wrong, to be a price for capacity provided payable per year. The point is, it’s going down.

Vestas

The 38% lift in prices Vestas is receiving for new orders is probably not fully flowing through to quarterly results. Also, like many companies, selling, general and administrative (SG&A) expenses are rising significantly, likely reflecting inflation of various sorts, but I am guessing in white collar salaries.

Management do seem as if manufacturing costs, the fundamental driver of prices and the future of the industry, are more or less under control.

The Vestas share price reflects investor views about the outlook for the company. The share price is still well above where it was five years ago and, on this view, recent results suggest investors haven’t seen any news in the past six months that would make them buy or sell.

Goldwind

The best of the bunch, in terms of current results, seems to be Goldwind. Goldwind is also interesting because its quarterly results presentation appears to show that, at least in China, bid-in prices are once again trending down.

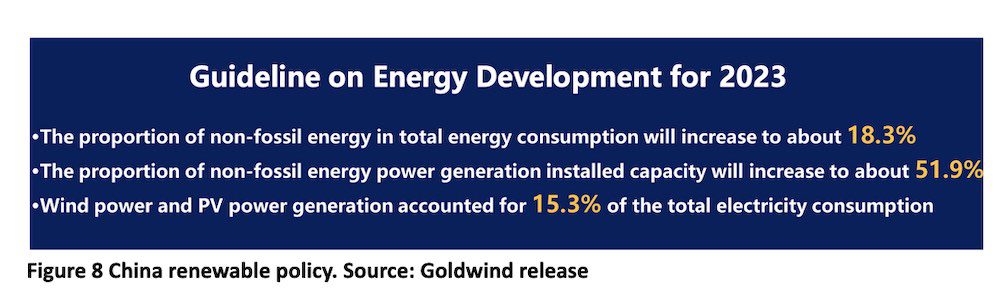

Goldwind also noted the following China policy goals for 2023.

Goldwind has remained profitable, or close enough to profitable, over the past couple of years.

GM

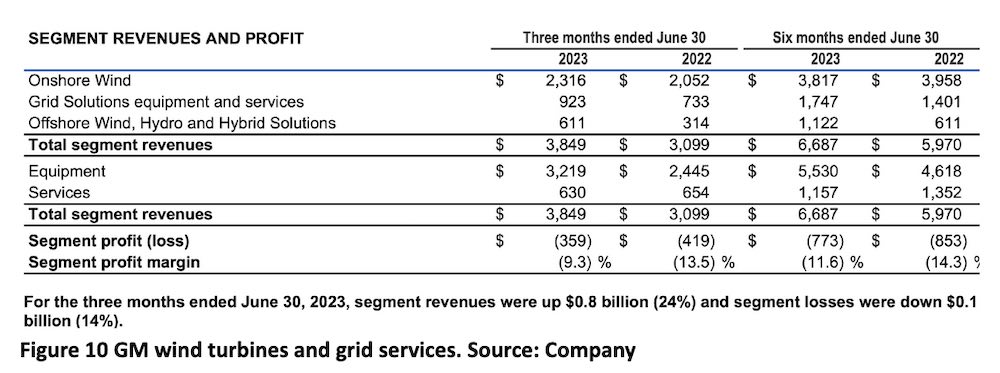

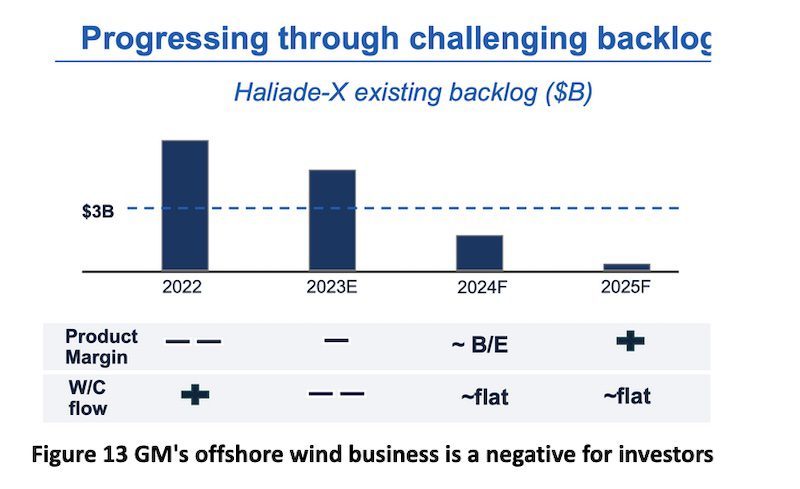

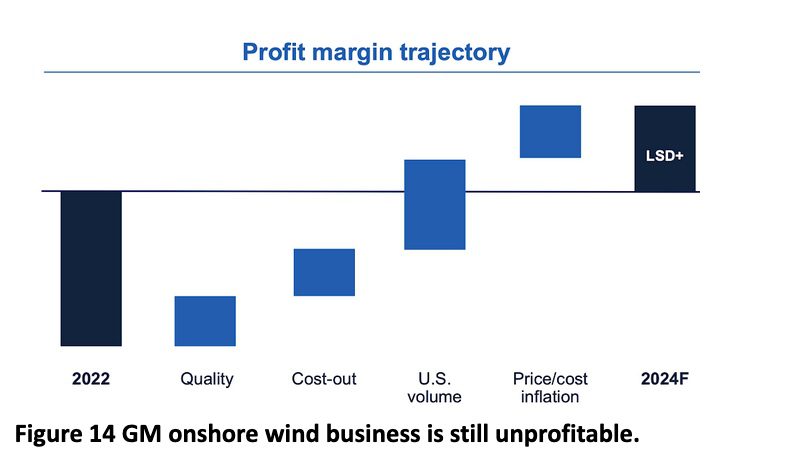

GM is in process of demerging its power business from aerospace. Right now its power business is unprofitable but improving.

Latest quarterly results of the wind segment as taken directly from the 10Q are:

The following snap shots are taken from the March 23 investor day presentation and may be of some interest.

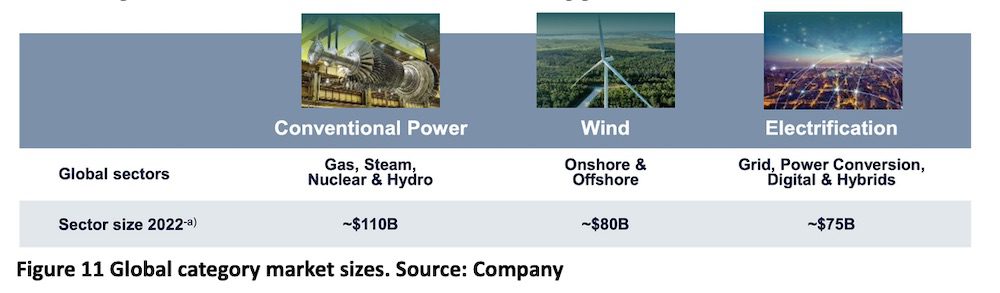

The demerged GM “Vernova” business serves the following global market:

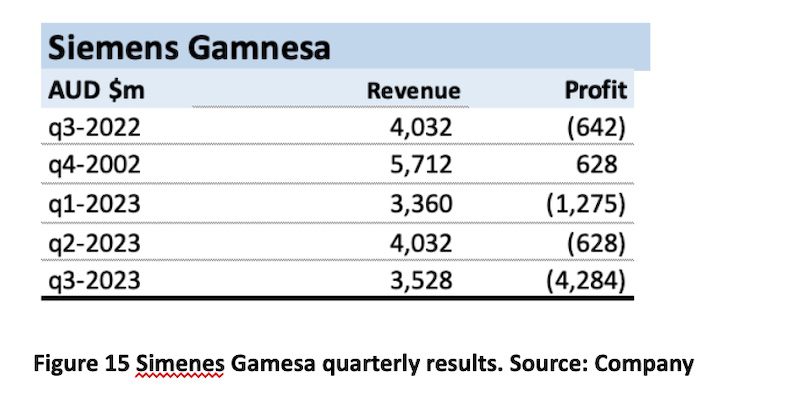

Siemens Gamesa

Siemens Gamesa is now part of Siemens Energy. Its recent results are consistently terrible.

The latest charges reflect charges resulting from detecting vibration in 4.x and 5.x turbines (of which there are 59k worldwide and no doubt some in Australia).

The vibrations are said to result “mainly” from blade and main bearing issues. The faulty blades and bearing will need to be replaced over a period of years. That’s only the onshore fleet.

The offshore fleet suffers from scaling issues, trying to do too much, too soon, with not enough skilled people. Challenges include for example trying to simultaneously produce two blade types during ramp up and producing blades and nacelles under the one roof.