Revising the generous fuel tax credits given to businesses should be a priority for the Albanese government, because keeping them would conflict with two other pressing priorities: reducing carbon emissions and repairing the budget.

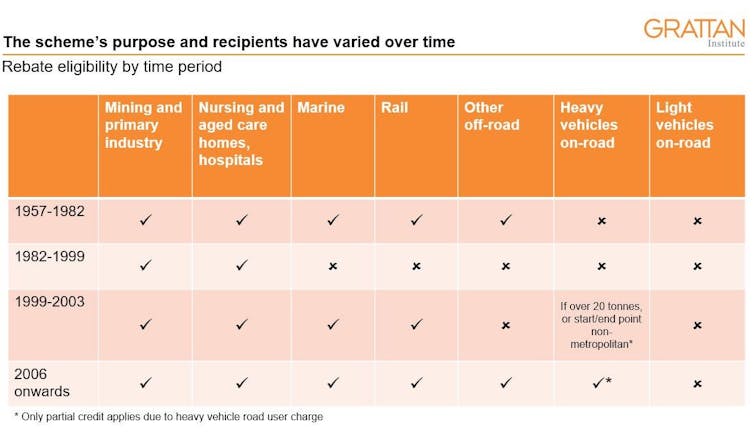

Fuel tax exemptions have existed for as long as the federal government has taxed fuel, starting in 1957. With the rationale for the tax being to pay for building and maintaining roads, initially all off-road users were exempt.

But the earmarking of all fuel tax revenue for spending on roads ended in 1959 – more than 60 years ago. With the tax becoming a general revenue-raiser, the rationale for exemptions or tax credits has shifted with the disposition of the government of the day.

The settings inherited by the Albanese government now cost the budget almost $8 billion a year.

As long ago as 1991, the Australian National Audit Office recommended the credit scheme “clarify its purpose and objectives”. Yet those objectives remain unclear today.

Who benefits most?

Previous governments have argued exemptions and tax credits support regional industries, and people living in regional areas.

In 1999, when the credit was extended to marine, rail, and some trucks and buses, the then-deputy prime minister (and National Party leader) John Anderson said the goal was to reduce transport costs, particularly for “those people living in regional, rural and remote areas”.

In 2006, when expanding the credit to include all off-road users and on-road vehicles weighing over 4.5 tonnes, the then-assistant treasurer Peter Dutton said: “This is good news for business, and regional Australia in particular.”

But if the aim of the policy is to support regional areas, fuel tax credits are a poorly targeted way to do so.

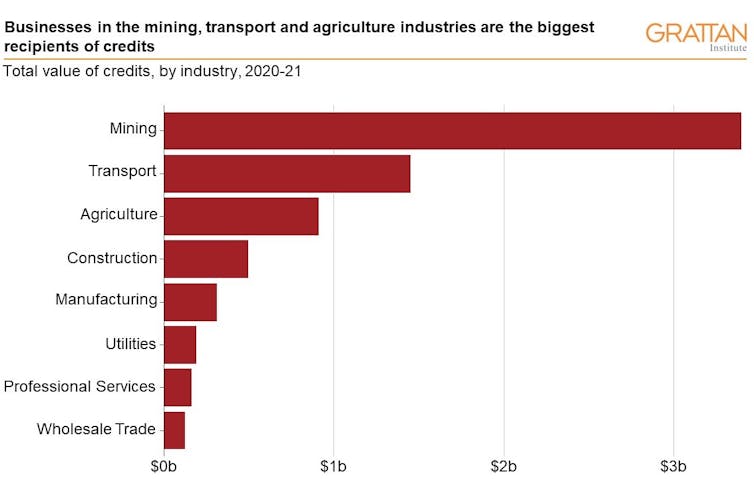

In the five industries that receive almost 90% of the value of credits, more than 60% of businesses, and 67% of employees, are in major cities.

There is no evidence fuel tax credits particularly benefit regional areas, or that they are more effective than other policies in doing so.

It is hard to avoid the conclusion that fuel tax credits are mostly a gift to the mining and agricultural industries – the only non-care industries that have always received an exemption from paying taxes on fuel, and the major recipients of fuel tax credits today.

Budgetary needs have prompted changes

Changes to fuel tax credits have also aligned with the budgetary needs of the government of the day.

In 1982, when government debt as a share of GDP was rising steadily, the Fraser government narrowed the scheme to just mining, primary industries and care industries. Many businesses previously exempt – including in rail, marine, construction and manufacturing – were forced to pay fuel taxes.

In 2006, the Howard government broadened the scheme during the mining boom when budget surpluses meant no net debt for the first time in 30 years.

Despite the straightened fiscal position the government now faces, the credit scheme remains unchanged.

Out of step with net zero and budget repair

The Albanese government has several growing spending obligations, particularly in health, aged care, disability care and interest expenses on its debt.

After stripping out the effects of temporary factors such as high commodity prices, there remains a stubborn gap between government receipts and spending of about $40 billion a year.

In a new report published by Grattan Institute, Fuelling budget repair: How to reform fuel taxes for business, we argue fuel tax credits should be removed for on-road users, and roughly halved for off-road users. This would save about $4 billion a year.

It would also reflect the environmental and health costs of diesel use.

Giving businesses tax credits for consuming fuel without having to pay for or reduce their carbon emissions is sharply at odds with the government’s goal of net zero emissions by 2050. Diesel combustion currently accounts for 17% of Australia’s emissions.

In 2020, the top five industry recipients of fuel tax credits directly produced more than half of Australia’s emissions. That share is expected to reach 64% by 2030.

As well as helping repair the budget, reducing fuel tax credits would signal to businesses that they need to consider emissions in their investment decisions, minimising the costs to future consumers, taxpayers and shareholders.![]()

Marion Terrill, Transport and Cities Program Director, Grattan Institute and Natasha Bradshaw, , Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.