Treasurer Josh Frydenberg has claimed gas exports will be a central pillar of Australia’s contribution to international climate action, but said almost nothing about the risks global warming poses to future generations as he launched the federal government’s latest Intergenerational Report.

In a speech that was meant to take a realistic look at Australia’s economic prospects over the next 40 years, Frydenberg also talked up carbon capture and storage and “clean” hydrogen as promising future industries, and boasted of Australia’s record of “meeting and beating” its notoriously unambitious emissions targets.

The Treasurer said gas would be one of the major opportunities for Australia in the global energy transition, because it provides “baseload power”. And he repeated the Morrison government’s line that “technology, not taxes” would get Australia to net zero, “preferably by 2050”.

But both Frydenberg’s speech and the 198-page Intergenerational Report document were notably light on detail or a sense of urgency about the many physical and transitional threats climate change will pose to future generations over the coming decades.

The Intergenerational Report is released every five years, and is supposed to forecast how demographic, technological and other structural trends will affect the Australian economy over the next 40 years.

Those 40 years will be the make-or-break period for climate mitigation globally, and will demand unprecedented and highly-disruptive economic transformation if the world is to wean itself off fossil fuels in time to avert environmental catastrophe.

By the end of those 40 years, China – the world’s biggest emitter and Australia’s biggest trade partner – has promised it will be carbon neutral. South Korea, Japan, Europe and the United States, meanwhile, say they will reach net zero emission 10 years earlier, in 2050.

Given many of these countries are prolific purchasers of Australian fossil fuels, this trend will have huge implications for some of Australia’s biggest exports, before you even consider the physical effects of climate change, or indeed the effects of carbon border tariffs.

But the report paid little attention to this major global upheaval, with no mention of climate change at all in the executive summary.

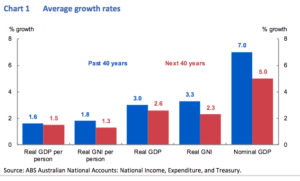

And while it laid out quite detailed modelling on future economic and population growth – both of which will be considerably lower than expected – and stressed the role of migration and the ageing population on the economy, it made no attempt to model any of the physical or transitional effects of climate change and decarbonisation. Instead, it made general statements on the risks, before going on to talk up Australia’s much-derided record on climate action.

Launching the report at an event hosted by the Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) on Monday, Frydenberg said “some sectors [would] need to adjust to falling demand for some exports, while new opportunities will be created in other sectors” as a result of climate change. He declined to specify which sectors he was referring to.

He went on to say Australia was “playing its part on climate change” and would use “technology… not taxes” to meet its targets. Australia aims to reduce its greenhouse emissions by 26-28 per cent on 2005 levels by 2030. The United States is targeting 50-52 per cent on the same baseline, while the European Union is targeting 55 per cent on 1990 levels.

When asked later to spell out the opportunities climate change poses, he mentioned hydrogen, carbon capture and storage, and gas.

“The opportunities for us are in things like hydrogen, carbon capture and storage, even some of the transition fuels, and it might be a fossil fuel, namely gas, but it’s important as a transition fuel because you need that baseload.”

This view is not backed up by energy experts, who not that the role of gas as a transition fuel in an increasingly renewable grid is limited to providing back-up “peaking” power at best, rather than a constant “baseload” power.

The report referred to “clean hydrogen”, which, unlike “green hydrogen”, can refer to hydrogen manufactured using fossil fuel feedstock, and capturing and storing the carbon dioxide emission.

The report dedicated around 10 pages to the subject of climate change, roughly divided between very general statements about what climate is and how it might affect the economy, and passages boasting about what the government is doing to mitigate and adapt to climate change.

Of the 119 words the report dedicated to “climate mitigation”, most were spent claiming Australia is doing its bit to reduce emissions, before briefly touching on the export potentials of “clean hydrogen”.

The 126 words dedicated to climate adaptation stated in the broadest terms that climate change would mean more extreme weather, then went on to say it was “implementing a broad range of reforms” including the “National Recovery and Resilience Agency, enhancing Emergency Management Australia, and establishing the Australian Climate Service”.

Perhaps its strongest words appeared in the section “Economic and sectoral impacts on a changing climate”.

“A reduction in real GDP associated with climate change would have a fiscal impact through reducing taxation revenue, as well as increasing pressure on expenditure. Other revenue sources such as fuel excise and mining royalties could also be affected by changes in demand and consumption related to a global transition away from fossil fuel use,” it said.

“The agricultural sector is particularly vulnerable to the physical effects of climate change, the resources sector is particularly vulnerable to the transition effects, and the financial sector is vulnerable to both.”

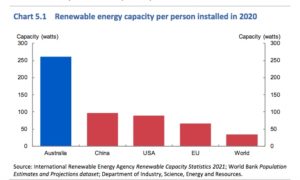

In a report that was full of charts, only one chart featured in the section on climate change. It showed the high amount of renewables per person installed in Australia in 2020, suggesting the government is more interested in defended its much-maligned record on climate than in identifying and addressing risks.

Following the section on climate change and the environment, climate only received one more mention, below the following chart.