There has long been an unofficial slogan to describe the behaviour and the impenetrable billing techniques of Australia’s energy oligopoly: “Confusion is profit.”

It probably remains true today, but there is one thing that is very clear: If you put a pot of money at one end of a 100 metre track and Australia’s biggest energy utilities at the starting blocks, they would all likely set new speed records, even if they had to leap over the hurdles – sometimes referred to consumer care – along the way.

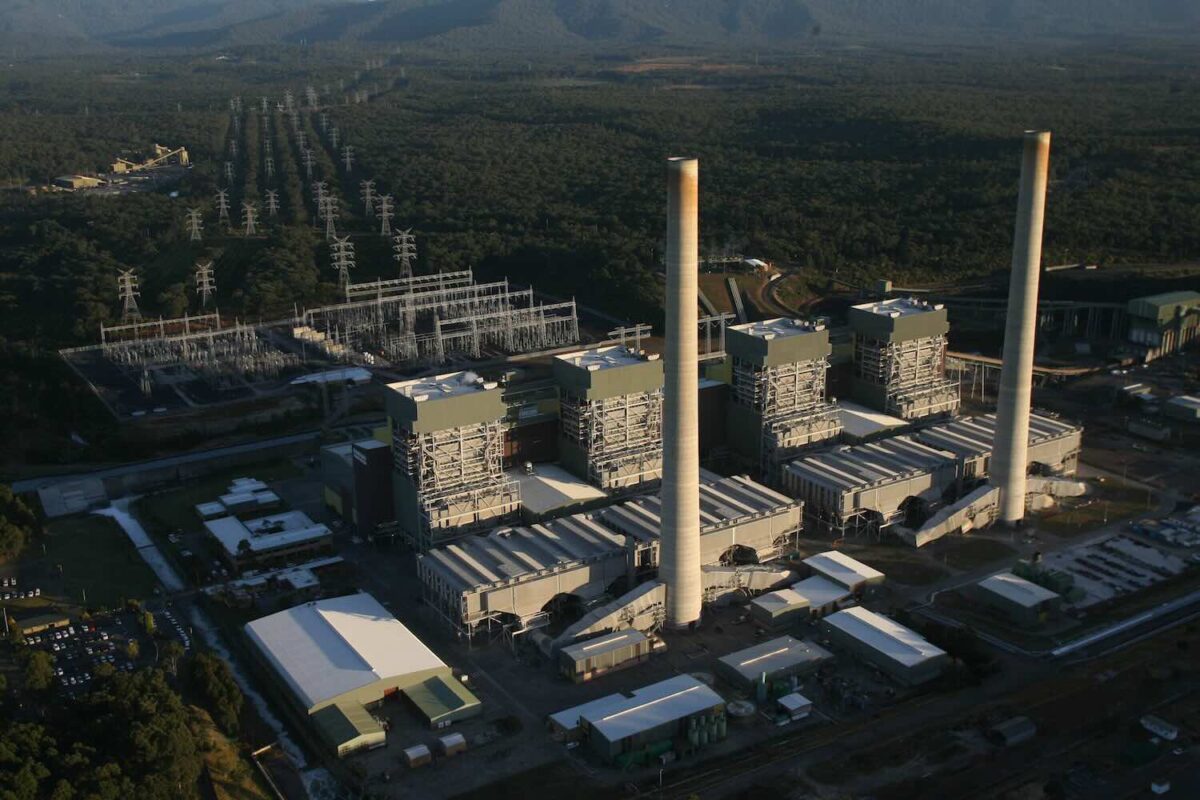

This week, the wholesale market price in NSW hit what is known as cumulative price cap, and an administered price has been imposed. It followed multiple unplanned outages at coal plants that took away more than 3 GW of capacity, a fall in wind energy output, and transmission issues that imposed further constraints on generators.

As the Australian Energy Market Operator made clear in a statement on Thursday, this did not mean that there was insufficient supply to meet what was relatively moderate demand.

But it did create enough scarcity in the market to present the energy industry with a market pricing opportunity, and in these situations the power utilities and market traders simply cannot help themselves.

Over more than 24 hour period they gorged over elevated prices and pushed the market price to the cap of $16,600 a megawatt hour so often that the automatic price cap had to be imposed, even before regulators and policy makers had time to scream ‘enough is enough’.

The market cap will remain in place, probably until next week, until the big utilities and traders can have a cold shower and enough competition comes back into the market to moderate their bidding strategy.

But it will have a devastating impact – not just on consumers, but also the weak-kneed politicians fretting about the impact of the planned closure of the Eraring coal generator, the country’s biggest at 2.88 GW, in August, 2025.

As we saw with the storms and the as yet unexplained tripping of the giant Loy Yang A coal generator in Victoria in February, prices at the market cap for even a few hours can dramatically distort the average prices that are used by regulators when they decide on setting guidance for consumers bills.

In Victoria, that brief price spike on February 13, even though it lasted just 2.5 hours, lifted the quarterly average wholesale price from $59/MWh to $76/MWh, according to the Australian Energy Market Operator.

And the price spikes in NSW on Wednesday and Thursday are likely to have even greater impact on the average NSW prices for the June quarter.

That will feed into the regulator’s assessment of what is a “fair price” to be imposed on consumers in future years, and on the NSW government as it worries about potential price spikes in the lead up to the 2027 state election. How much money does Origin Energy want to keep its plant open?

So what exactly happened this week? It’s hard to know at this stage, and no doubt the Australian Energy Regulator will initiate an investigations – as it is required to do – and release its analysis of events and bidding strategy …. in about four months time, when the incident has faded into distant memory.

What we do know as that more than 3GW of coal fired capacity was missing from the market. “A number of major generation units went offline in New South Wales while scheduled maintenance was also taking place on transmission lines,” AEMO said in its statement.

Two 720 MW units at Eraring were out because of “short term unplanned outages”, according to a company spokesperson.

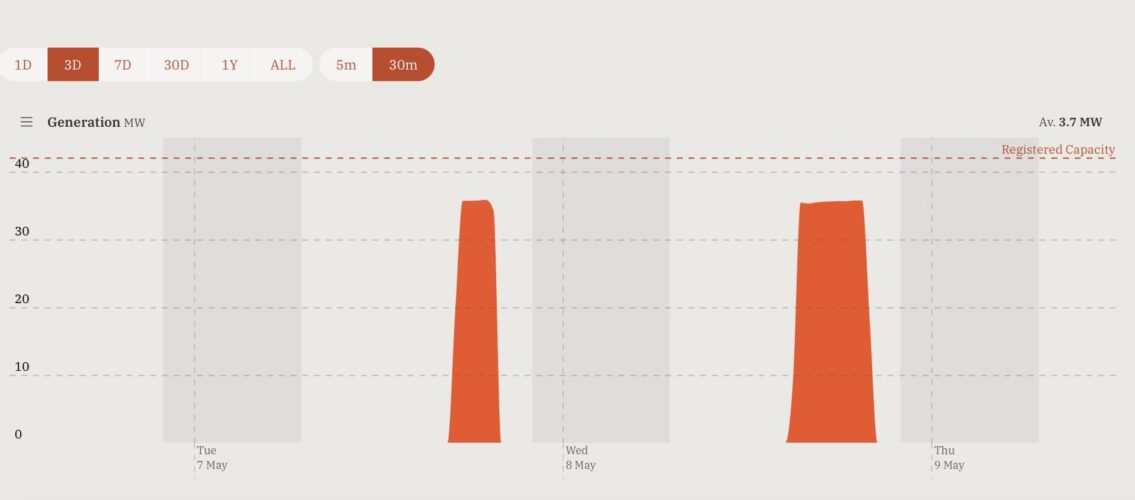

Another gigawatt of coal capacity was missing from the nearby Vales Point power station, where output fell suddenly on Wednesday morning as one of its units went off line and the remaining unit was limited to little more than 200 MW. That is well below its stated capacity of 1,320 MW.

The Bayswater coal plant in the Hunter Valley was also operating around 500 MW below its capacity, apparently because of the transmission issues cited by AEMO. The sun had set, so there was no solar, and wind output was also lower than average.

What happened next is a similar story to the market. Faced with reduced competition, but no threat of shortfalls, the big generators turned to the dirtiest and most expensive technologies in their portfolio.

Origin, which hasn’t bothered to build any new capacity since announcing the planned early closure of its Eraring generator more than three years ago, turned on its rarely used diesel generators at Eraring, and the federal government owned Snowy Hydro had its peaking gas plant at Colongra working hard.

It won’t be clear until the AER does its investigations who it was that bid the price up to the market cap of $16,600/MWh, about 50 times the actual cost of the most expensive generation.

But it’s normally a well-rehearsed construct. The generators only need a few megawatts of capacity at the market cap to have the price of every single megawatt injected into the grid subject to the same price for that trading period. The bill is duly sent to the consumer.

The only customers that have any protection are those wealthy enough to buy a form of insurance known as market caps – sold to them by the very same organisations that have the ability to bid the price to the market peak.

If that sounds like an arrangement dreamed up by Vito Corleone, you would be right, but such was the market’s regulatory capture when the rules were designed a few decades go.

And get this, the market price cap is due to go to more than $22,000/MWh in just a few years because, the generator owners have convinced the regulators and rule makers, that is the (ransom) price needed to keep these machines on the grid.

This is considered a “normal” part of the way the electricity market conducts its business. It’s not a lot different to the way other oligopolies operate in Australia, but little wonder that consumers are losing faith, and are turning to their own energy resources. At least some of them have options, even if the rules and regulations are piled high against them.