As a follow up to yesterday’s article on “parenting advantage” and its implications for utilities, this article will address the problems associated with capital allocation as centralised and distributed energy markets continue to diverge.

Essentially, the curse of capital allocation is where utilities are faced with making a choice about what they do with the free cash flow they are generating:

- Give the money to shareholders

- Invest in the centralised low growth fossil fuel assets

- Invest in the distributed high growth renewable assets.

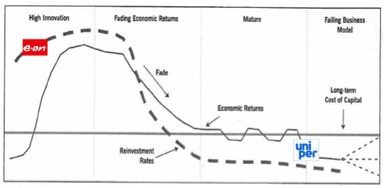

Continuing as we did yesterday, using the European utility EON and its respective demerged entity Uniper as a reference point, the corporate competitive life-cycle analysis shows where these assets sit in this increasingly distributed market. Like the strategic problems associated with parenting advantage the issues associated with maintaining returns above your cost of capital are equally challenging across a utilities diverse asset base.

Like parenting advantage, the capital allocation curse for utilities exists because their asset bases are cannibalising each other’s markets but also because the innovation cycles (infrastructure vs technology) are very different for these two respective asset bases.

Solar, wind, battery and software energy companies are much more like technology companies, such as Apple, who can commit invested capital (R+D and manufacturing) knowing that the Iphone 4, 5 and 6 will all cannibalise each other within a two-year period and still be able to achieve a return above their cost of capital.

While the payback period for a solar, software and storage system is clearly not two years, the speed with which that sector is innovating its flexible and modular solutions is well established and continuing to scale. (Swanston effect)

For those people less familiar with economic models, the bar chart of cash flows – above – shows the product innovation cycle for an infrastructure investment like a coal-fired power station or nuclear plant. The red bars at the start represent the planning and asset building phase with a likely clean up or demolition cost at the end of its life and the blue bars a simplistic constant set of cash flows over the life of the asset.

It is against the backdrop of this set of cash flows, and the corporate competitive life cycle of these assets, along with the need for high levels of capital expenditure as they approach the end of their working lives, that the capital allocation curse really starts to bite.

For a new-build, what you are asking a CFO to do is take a bet (large capex investment) that the asset they are building will still be competitive in the market for the next 25-40 years – post the four-year construction time.

The big problem this asset cash flow chart highlights is just how risky large (even supercritical) thermal generators are relative to the distributed market solutions, which by their very nature will be increasingly modular, agile and price competitive.

Many people will argue even if you were to start building one tomorrow, it would be financially stranded four years from now, before the first electron hits the grid and the final coat of paint has dried.

The lesson from Europe (EON and RWE) is that allocating capital between these diverse assets in these diverging markets has now become so hazardous that the best thing to do is demerge them into separate listed entities.

By splitting the asset base in this way you address the internal conflict of capital allocation in three ways:

- Allow for a strategy that could be tailored to both EON and Uniper’s specific markets;

- Decrease the need for management trade-offs of both capital and management expertise;

- Allow for refining of the activity systems that underpin the competitive advantage so that EON, in particular, will be able to position as agile and flexible as the distributed market continues to rapidly evolve.

All of these trade-offs and many other internal conflicts are largely resolved as a result of this strategic pivot which investors priced at about €2 billion, post the demerger.

Prior to the strategic splitting of the assets, senior management would have been constantly at war with each other over what was in the interests of shareholders: to cling onto the declining revenues, or bite the bullet and invest in the high growth distributed opportunities.

Key to unpicking this curse of capital allocation for those companies who head towards the battlefield of a brown to green transition (tomorrow’s article) will need to be a very good, very well executed corporate strategy that more people are likely to fail at than to get right.

Not only will it need to be a great strategy, it will need to be believable, effectively communicated to the market, and accepted by shareholders – who may have to accept no dividends for a couple of years.

The billion-dollar question is, can this curse of capital allocation be managed in a way that actually creates value (or at least minimises loss) for shareholders as the energy markets are disrupted? To date, the evidence from both Europe and NRG in North America is that they can’t.

Matthew Grantham is a guest contributor for RenewEconomy. Reproduced with permission.