It has now been three months since the release of the Finkel Review Report and its recommendation for a Clean Energy Target – and the federal government seems no closer to deciding what the renewable energy policy landscape will look like after 2020.

Adam Bandt recently pointed out that Labor’s willingness to vote for anything that will shore up support for the renewable energy industry provides an opportunity for the Liberals to propose any combination of weak schemes (Emissions Reduction Fund, anyone?).

Alternatively, in-fighting within the Liberals is leading to the renewable energy policy space being so toxic that our Prime Minister appears to prefer it isn’t discussed at all (unless it’s a token fly-over in a helicopter of an already existing asset, spruiking an already announced project).

In the meantime, individual states are ‘going it alone’ with renewables, leading to a patchwork of policies that don’t necessarily integrate well with a national market.

Large-scale renewable energy companies are benefitting from a reduction in the cost of renewable energy investment and the support of state governments, but are also variously concerned about: network connections; profitability impacted by 30 minute settlement periods; and the potential for spread of grid-support requirements that will see excessive physical inertia ‘support’ for wind farms.

Agencies are pushing for “demand-side measures” (eg batteries and demand management (AEMO) but have delayed changes to the ’30 minute settlement period’ (AEMC).

Consumers, on the other hand, have to worry about the ‘gold plating’ of networks, retailers choosing to move people onto high cost standing rate tariff structures, variability in feed-in tariffs or the potential for ‘solar taxes’, not to mention the odd dodgy solar retailer.

So what can be done?

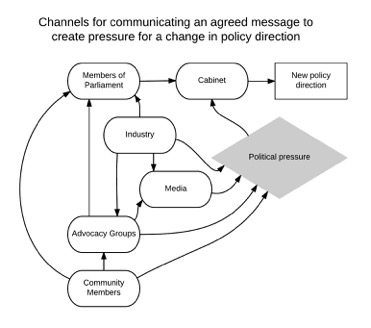

According to my research, published last month, there is the potential for industry and community to influence the direction of energy policy. However, this requires the development of a clear and consistent message – i.e. something that can be acted on – and requires industry and community stakeholders to work together.

The example used in my research is Western Australia’s premium feed-in tariff. In the 2013 budget it was announced that the premium feed-in tariff available to existing solar households would be reduced, and then discontinued, well ahead of the initial 10-year timeframe. This would see a reduction in financial returns for approximately 75,000 WA householders. It also represented a backflip on a WA government commitment to support the local renewable energy industry.

The response to the decision to discontinue access to the premium feed-in tariff was rapid and effective.

Industry advocacy groups quickly contacted members of parliament to make them aware of the likely consequence of the decision – unhappy voters and the perception of an unreliable government.

A public advocacy group, Solar Citizens, created an online petition to gather the names of people opposed to and/or affected by the decision (almost 10,000), which in turn created awareness of the government’s policy change and its potential impact.

Many householders, some of whom I spoke to, contacted their local members of parliament noting their displeasure about the proposed change – and that the decision was leading them to consider voting differently in the next state election. This proved important in leading individual MPs, concerned about maintaining their seats, to contact the state minister for energy and treasurer about the potential for reversing the decision.

Finally, renewable energy industry and public advocacy groups engaged with media organisations to spread the message about the government’s decision.

Interestingly, my research indicated that many of the people we believe have the power to influence the energy industry – including those in energy agencies and utilities, members of parliament and government representatives – don’t necessarily have much influence in the overall direction of energy policy.

Instead, policy is developed by Cabinet, sometimes seemingly without any thought for consumers or industry. (Turnbull’s recent claim that AGL was considering extending the life of the Liddell coal power plant – only to be rebuffed by AGL CEO Andy Vesey – is an extreme example of this).

Based on my research, the best chance there is to influence the direction of energy policy is to create a mass of political pressure. If industry and agencies agree on a particular message – and this message is strongly enforced and promoted by a mass of the voting public and media agencies – there might be the potential to influence the direction of government policy.

There have been clear attempts at this in the past. For instance, when the Clean Energy Council and the Australian Aluminium Council, two groups with typically opposing views in relation to renewable energy policy, released a joint statement requesting the Abbott government to finalise a course of action on the Renewable Energy Target.

The decision to come together behind a common voice was effective, not only in highlighting to conservative members of parliament that the Renewable Energy Target genuinely impacts industry, but the merging of diverse voices proved interesting to the media as well.

(In this case the ‘push’ wasn’t successful – it was another six months before an agreement was reached. But this was also at a time when public interest in the Renewable Energy Target was waning – there are only so many review reports the public can take before it ‘checks out’.)

Perhaps the problem, as it currently stands, is that the complete policy black hole surrounding renewable energy at the federal level has left it almost impossible to craft a clear message that industry members, community members, agencies (if independent) and parliamentarians can get behind. It’s hard to tell where this will land at this stage – but there are plenty placing confidence in the new AEMO head, Audrey Zibelman, to be able to create messages that all can support.