The US is funding direct air capture to the tune of $US1.2 billion ($A1.8 billion), but the decision has met with criticism that it’s an expensive gimmick to facilitate more fossil fuel extraction.

The Biden administration will fund two direct air capture hubs in Louisiana and Texas that propose to remove at least one million tonnes of carbon dioxide directly from the air annually.

It is the first phase of a $3.5 billion funding pot for direct air capture, that was set aside last year in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and plans to establish four hubs in the coming decade.

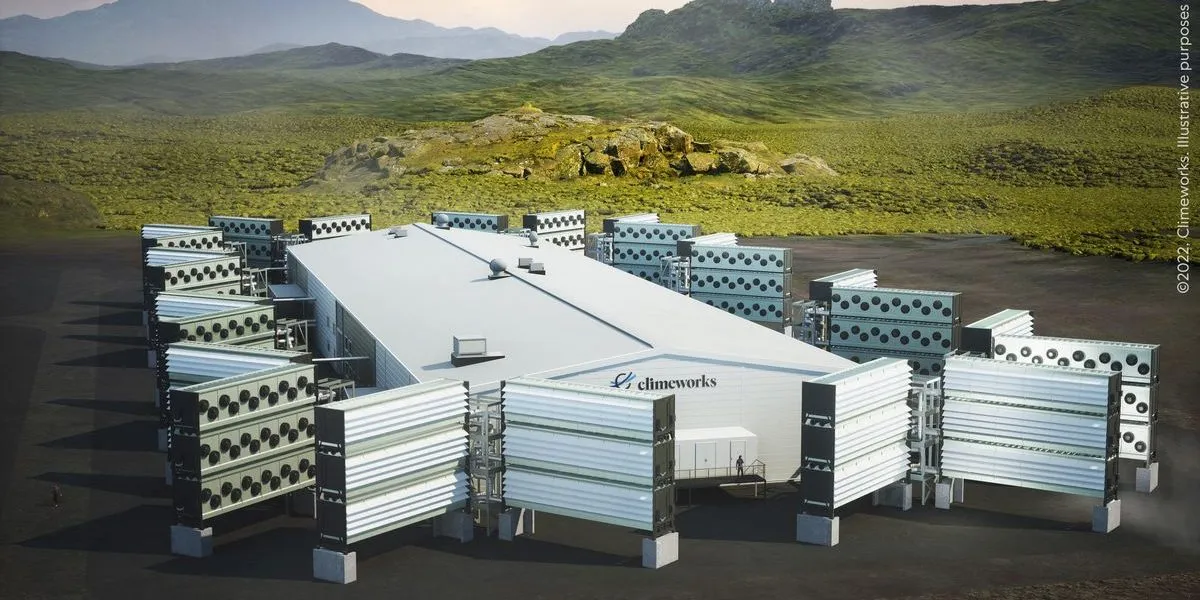

The Louisiana project is run by Battelle, Climeworks Corporation and Heirloom Carbon Technologies, while the South Texas hub was proposed by Occidental Petroleum’s subsidiary 1PointFive and partners Carbon Engineering Ltd and Worley.

The Texas hub is the most ambitious project globally, with plans to have an initial 500,000 tonne per annum hub working by 2025. 1PointFive says it will build 100 similarly-sized facilities globally by 2035.

Direct air capture, or DAC, uses a chemical reaction to effectively suck carbon dioxide from the air. It can then be used for different applications or stored underground.

Just a way to enable fossil fuels

However, atmospheric scientist Mark Jacobson says the concept is a waste of renewable energy which could instead be put to work reducing the amount of fossil fuels used in economies.

“DAC requires a lot of electricity for extracting CO2 from the air and compressing it,” Jacobson wrote on LinkedIn following the announcement.

“Even in the best case, where the electricity is renewable, that renewable electricity is then prevented from replacing a fossil source, such as coal or gas, whether for grid electricity or an industrial process.”

Not only does using renewable energy to replace coal, for example, reduce the amount of carbon in the atmosphere, it also eliminates air pollution from coal burning and mining, and from associated infrastructure.

Direct air capture, on the other hand, delays the reduction of fossil fuels by requiring more power in the grid to support it.

Jacobson says three quarters of carbon dioxide captured is used for enhanced oil recovery.

“[It’s] a process by which 40 per cent of the CO2 is lost right back to the air and that results in more oil being burned, creating more CO2 and air pollution,” he writes.

“Alternatively, captured CO2 is proposed for use to produce other combustion fuels (electrofuels) to replace gasoline. This requires even more energy and materials and allows combustion to continue, permitting air pollution and more CO2 emissions to continue. Better to use electric vehicles.

“A third option is to store the CO2 underground. However, there is little financial incentive for this.”

In a 2019 paper Jacobson wrote on the topic, he says direct air capture systems powered by natural gas increase air pollution by increasing fossil fuel use consumption and upstream mining.

Running one on renewable energy does not increase or decrease carbon dioxide pollution, whereas using that electricity to actively replace fossil fuels has a measurable effect.

Necessary as a backup technology

But investing in clean energy and technologies is not enough, direct air capture advocates say.

The CSIRO said in June that the world must remove the equivalent of an MCG volume of carbon dioxide from the air every four seconds, or about 2901 tonnes of CO2.

“Direct air capture is a really hot topic worldwide at the moment,” said CSIRO Sustainable Carbon Technologies lead Dr Claudia Echeverria.

“As technologies advance and diversify around carbon capture, utilisation and storage, it’s attracting more and more global scientific research and commercial interest.”

CSIRO researchers are working on a variety of different technology innovations in direct air capture, including amine liquid capture technology for DAC which led to the development of the Ambient CO2 Harvester (ACOHA), a collaboration with Santos using sorbent material – a combination of 30 per cent solid sorbents and 70 per cent liquid amines which is set to be tested at the Moomba gas plant in South Australia.

The first direct air capture unit was launched in 2010 but as of last year, the International Energy Agency noted 18 small scale facilities worldwide, operating in Canada, Europe and the US.

The biggest is in Iceland which captures 4000 tonnes of carbon dioxide a year.