A new type of catalyst developed by Australian researchers could open the way for zinc-air batteries to go large, and even make the technology applicable at grid-scale installations.

Currently zinc-air batteries are a promising new technology, but until now they are tiny and only able to be used in devices such as hearing aids.

However, Monash University researchers say they have found a way to add individual cobalt and iron atoms as catalysts that make the oxygen reactions faster and more efficient. This in turn allows the technology to be supersized.

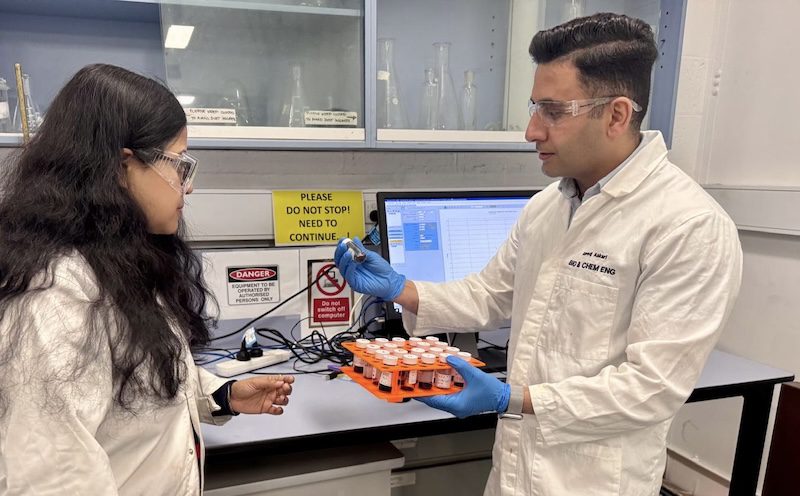

“By engineering cobalt and iron as individual atoms on a carbon framework, we achieved record-breaking performance in zinc-air batteries, showing what is possible when catalysts are designed with atomic precision,” co-lead author pHd student Saeed Askari said in a statement.

“Our advanced simulations revealed that the cobalt-iron atom pairs, combined with nitrogen dopants, enhance charge transfer and optimise reaction kinetics, solving one of the biggest bottlenecks for rechargeable zinc-air batteries.”

The experiment resulted in a battery that lasted 74 days with 3570 charging cycles, when cobalt and iron are used as the cathode.

The unit “demonstrated outstanding performance” with a power density of 229.6 mW.cm−2 and an energy density of 997 W.h.kg−1, the paper published in Chemical Engineering Journal found.

Co-lead author Dr Parama Banerjee says running a rechargeable zinc-air battery is a milestone for the field.

“It demonstrates that this technology is ready to move beyond the laboratory and into practical applications,” she said in a statement.

“These catalysts not only solve a key bottleneck for zinc-air batteries, but their design principles can be applied across the energy landscape – from fuel cells to water splitting – offering broad impact for clean energy.”

Metal-air to the rescue

So-called Metal-air batteries are one of the many technologies that scientists are racing to development as a competitor to lithium-ion storage, but they’ve been “set to challenge” that chemistry for decades, as reported by Renew Economy in 2013.

The breakthroughs have kept coming, with iron-nickel being sold in as the catalyst that could do it in 2022, and Edith Cowan University researchers claiming their structural redesign in 2023 might see zinc-air batteries in cars.

There are real benefits to zinc-air batteries, including potentially higher energy density, cheap manufacturing and safety as the chemistry is less volatile, making them theoretically ideal for cars and planes.

The problems are also myriad.

Slow oxygen reaction rates lead to high charge/discharge overpotential, low efficiency, reduced energy capacity, and shorter cycle life, the Monash paper said.

Adding a metal catalyst isn’t an easy fix either though. In the wrong structure they can also slow the zinc-air reaction, which is why the Monash engineers settled on the ultra-thin 2D sheet that meant the catalysts would help, rather than crowd out, the reaction.

The researchers heated zinc acetate and potassium chloride to 930°C for three hours in an atmosphere of concentrated nitrogen gas. That meant they could turn the mixture into ultra-thin carbon sheets with pores that other atoms could slot into.

The best performing atoms in this case were cobalt and iron, which were better at supercharging the zinc-air reaction over standard commercial catalysts made from expensive metals such as platinum and ruthenium.

Want the latest clean energy news delivered straight to your inbox? Join more than 26,000 others and subscribe to our free daily newsletter.