For some time, Australia’s federal government has turned to renewables for global bragging rights on climate action. On a global scale, Australia is deploying renewables relatively quickly. But it also remains among those with the highest coal share.

This apparent contradiction is explained by the fact that Australia is moving from a low base quickly. But the key question – is it quick enough? – gets lost in the government’s attempts to present the changes as sufficient. It is not true: far more effort is needed to accelerate zero emissions power in Australia, and the government is falling badly short.

It’s worth pointing out that several significant records were broken in 2020, according to a new report released by the Clean Energy Regulator (CER), but also that all signs point to a levelling off of growth in Australian renewable energy.

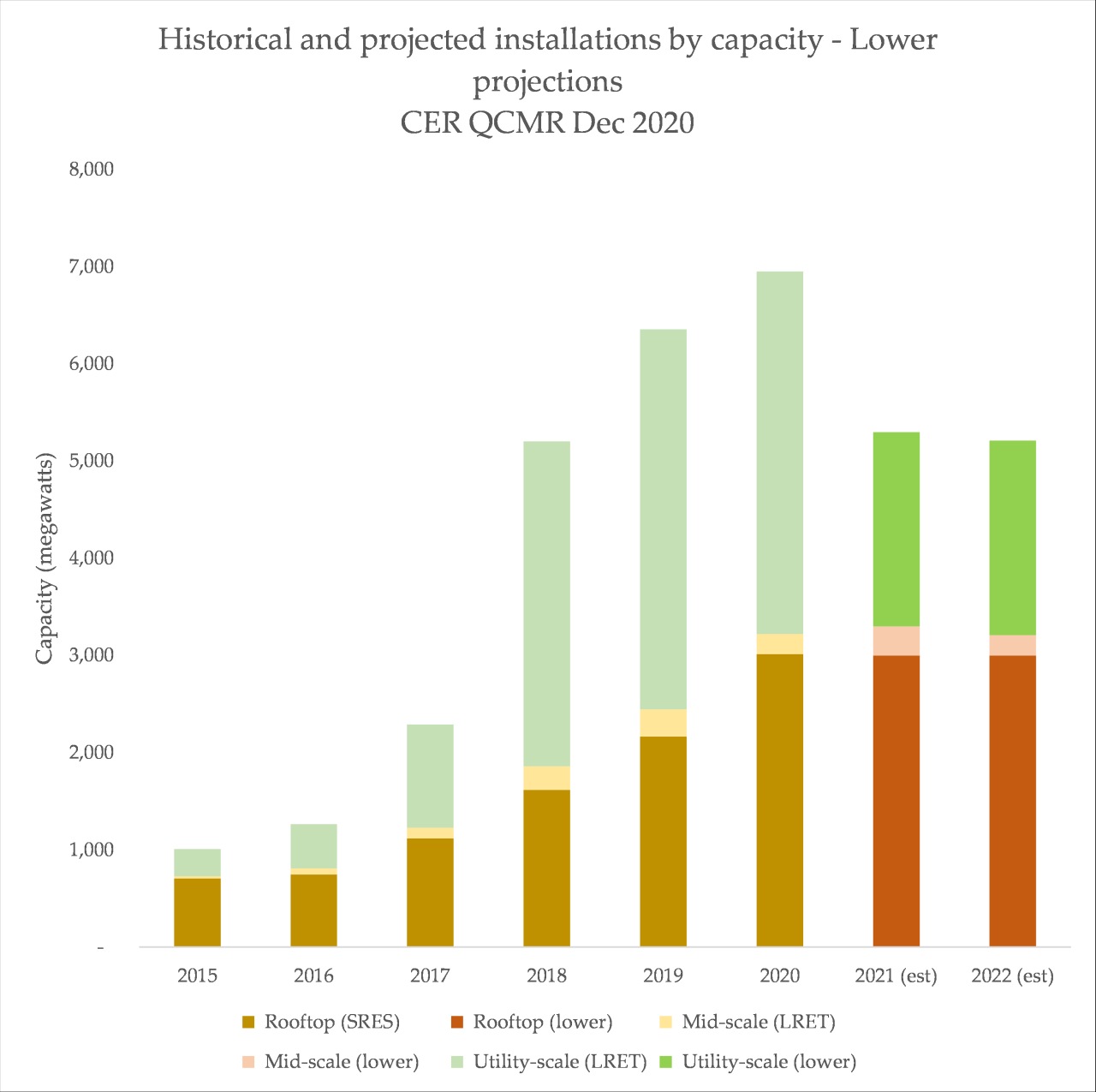

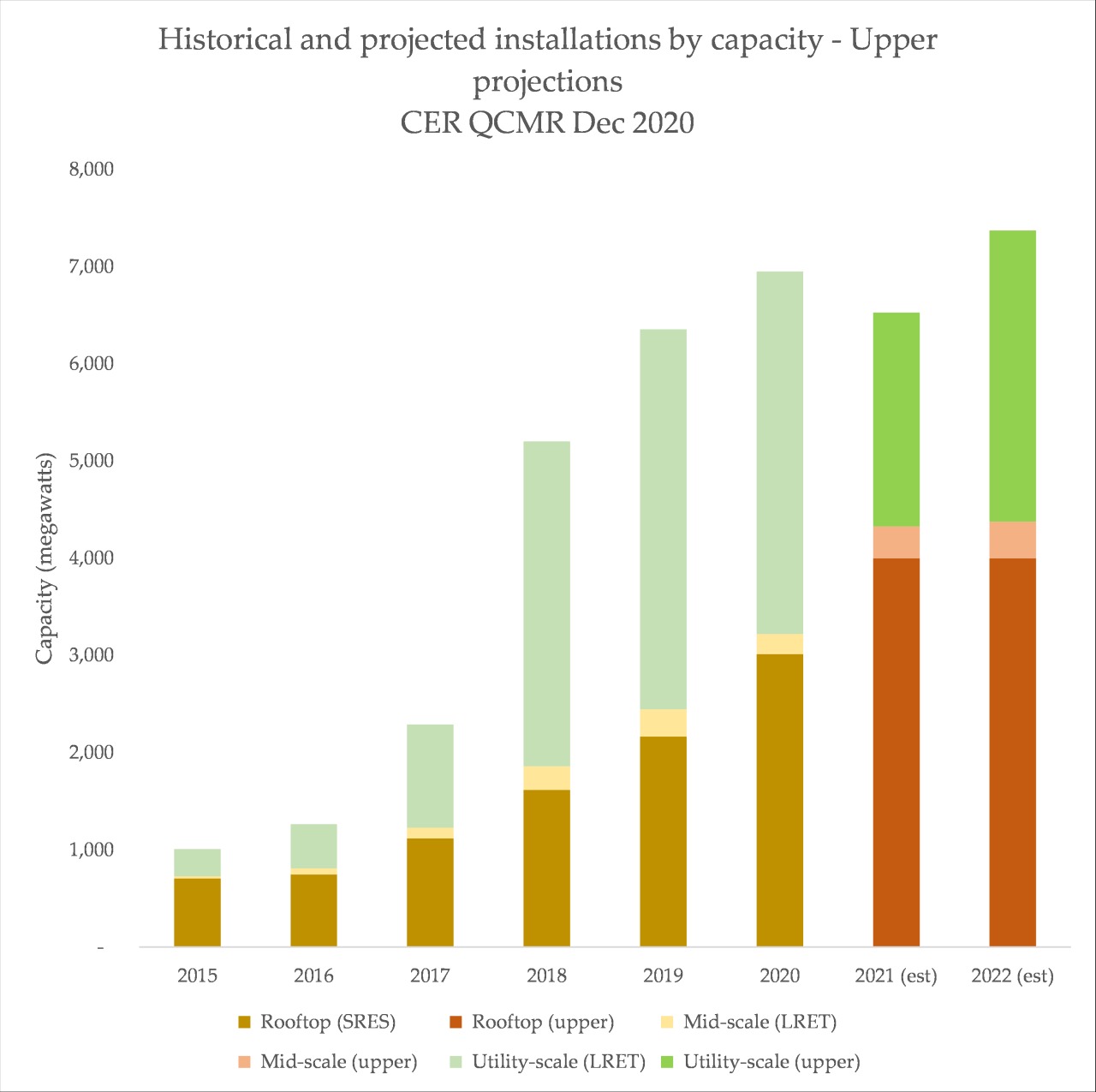

In 2020, 2.7 gigawatts of utility-scale renewable energy achieved financial close in Australia, an increase of 17% from the previous year. 3 gigawatts of rooftop solar PV capacity was installed, up by 40% from 2019. “This outcome exceeded the Clean Energy Regulator’s original 2020 estimate of 6.3 GW; and was primarily driven by several utility-scale power stations commencing generation and being accredited sooner than expected”, wrote the CER.

The report points to increased work from home arrangements and a focus on ‘home improvement’ as part of the reason the small-scale solar sector grew so rapidly. In terms of large-scale renewables, wind dominated due to the Stockyard Hill, Dundonnell and Moorabool wind farms, but the CER predicts a shift back to large solar in 2021.

Dig into the data, though, and you quickly realise that the days of rapid growth may not be sustained without new interventions.

Emissions reductions

The CER reports that for 2020, the combined impact of renewable energy growth resulted in emissions reductions of 37 megatonnes of CO2 equivalent, due to the displacement of fossil fuels by new renewable energy. Cumulatively, since 2011, renewables have saved 232 MTCO2-e. The emissions reductions from the RET continues to dwarf those from the issuance of carbon offset permits (Australian carbon credit units, ACCUs).

Recently, the price of ACCUs has surged due to rising demand from corporate emitters, and the CER has recently announced a scheme to track corporate usage of carbon offsets. The scheme has been heavily criticised, as offsetting emissions using avoided deforestation or vegetation is a poor substitute for actively reducing the burning of fossil fuels.

Investment peaks, but won’t last long

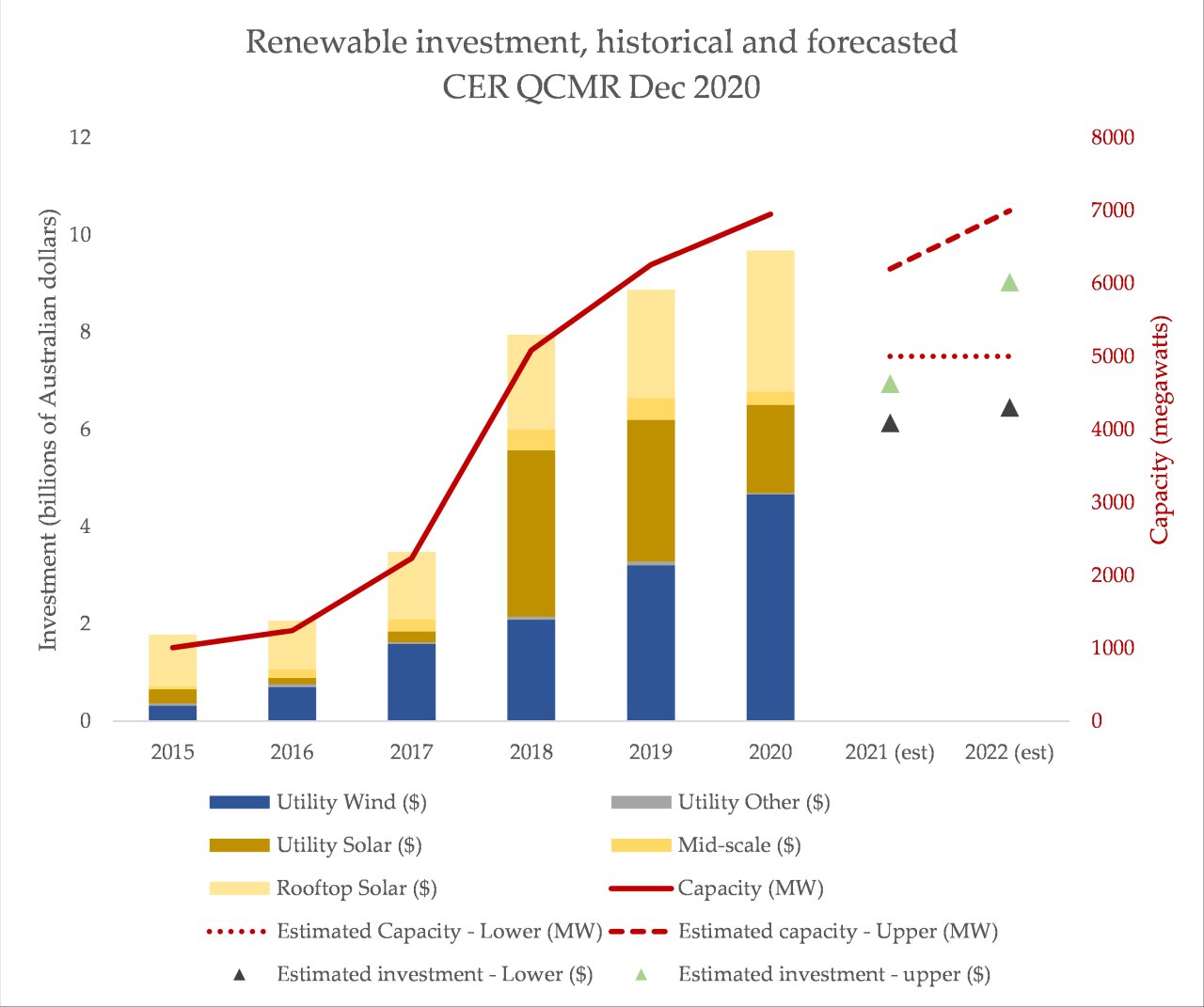

The CER goes to some lengths to highlight that a drop-off in renewable energy investment has not occurred, despite the point at which the renewable energy target stops rising being reached in 2020. Most of the investment has been underpinned by government and corporate power purchase agreements. However, the CER also forecasts that the capacity of renewable energy added in 2021 and 2022, along with the total amount of investment in renewable energy, are likely to remain at the same level rather than growing, as has been the case over the past half decade – in the best case. In the worst case, renewable investment and new capacity will plummet over the next two years.

The CER highlights that declining wind and solar costs mean even with relatively lower investment amounts, more capacity can be built. But their own forecasts range between stagnation and collapse. This is not reassuring. While the report specifically complains that “Analysts and market commentators have been citing a collapse in renewable investment for several years. This has not eventuated”, their own forecasts highlight it as a real possibility in the coming two years.

2020 saw the highest rooftop PV growth on record, driven by WFH home improvement

Examining the quantity of change between years, it’s clear that 2020 saw the biggest jump in absolute installed capacity of rooftop solar PV in Australia, with an increase of around 850 megawatts between 2019 and 2020. The rate of change has been accelerating since 2016, but 2020 set a clear record for rooftop solar installations in Australia. The CER’s expectations for 2021 are wide, ranging between the same amount of solar installed or another new record growth level of around 1,000 additional megawatts. It is by far the most optimistic story within renewables in Australia.

The final quarter of 2020 saw 950 megawatts of rooftop PV installed, “the single largest quarter of installed capacity since the scheme began in 2001”. And the easing of Victoria’s COVID19 restrictions in October 2020 also contributed to the high burst of solar installations towards the later end of the year. The average capacity of installed systems was also the highest on record.

2,677 battery installations also occurred in the final quarter in 2020, only a slightly increase on the same quarter in 2019.

Signs of a slowdown

In mid 2020, a spat emerged between opposition leader Anthony Albanese and federal Energy and Emissions Reductions Minister Angus Taylor. Taylor claimed renewables were booming under the Coalition government, and Albanese claimed the focus on investment was misleading, and that new installations were falling.

Albanese: “We've seen investment in 2019 fall off the cliff for renewables” Wrong again @AlboMP. @CERegulator estimates 6.3GW of new renewable capacity installed in 2019 ⬆️ 24% on previous record set in 2018. 🇦🇺 invested $7.7bn in renewable energy in 2019 https://t.co/Kt5UuootTy https://t.co/zTWR7PubOn

— Angus Taylor MP (@AngusTaylorMP) April 24, 2020

— Anthony Albanese (@AlboMP) April 24, 2020

Though the trend for investment in renewables has been increasing over the past half decade, the amount by which it is increasing is itself slowing down.

Between 2019 and 2020, investment increased by $0.8 billion AUD. Between 2018 and 2017, that was $4.4 billion. That is reflected in the capacity additions, but also shown in the data relating the amount of new renewable energy committed each year. 2020’s total committed clean energy was higher than 2019, but lower than 2017 and the peak of 2018. At best, things are levelling off when they should be accelerating.

While renewable growth has been substantial, a sustained increase in investment – and commitments and accreditations – is required to align with the rapid decarbonisation required under global climate targets. In Australia’s National Electricity Market, for instance, a steep upwards incline in the proportion of energy supplied from zero carbon sources is required to hit around 97% by 2030, the target advocated for by prominent climate experts and analysts.

Falling wholesale prices, confusing regulatory signals and the total absence of any clear climate policy from the federal government are all contributing to what seems to somewhere between a freeze and a drop in Australian clean energy. Coal plants may retire earlier than expected, but that’s very unlikely to be sufficient. What’s needed is an acknowledgement that though Australia is making some notable strides in renewable energy, it is not adding up to what’s needed to hit climate goals.