Melbourne-based battery company Relectrify is open for sales after officially launching its “world-first” commercial-scale battery product, which has been more than 10 years in the making.

CEO Jeff Renaud says the company is targeting the commercial and industrial sectors initially with the AC1 system, and it hopes that first orders are received in the next few weeks, with deliveries to start from April next year.

Relectrify is being helped by a $25 million grant from the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) that will help the company make and install the first 100 MWh of its AC1 systems.

The AC1 battery is a 250 kilowatt (kW), four hour unit made up of 24 “packs”, in turn made up of off-the-shelf cells and hardware.

The Australian bit is the innovative operating system which individually controls each of the 24 cells within a pack, a system that allows it to both produce AC electricity and get 20-30 per cent more power out of a whole pack.

ARENA says this is a “world first” because it means a battery management systems replaces the usual inverters, reduces degradation, and allows for 20 per cent more energy to be produced over the life time.

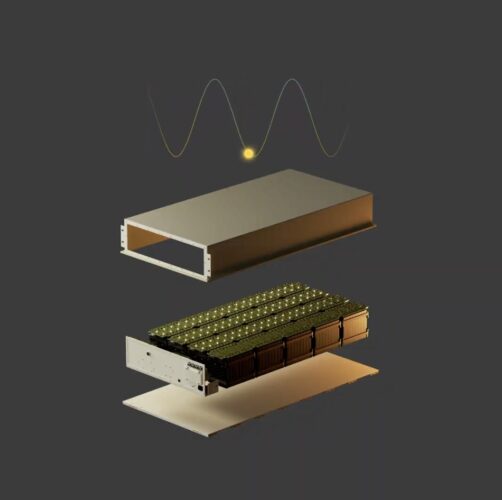

The operating system itself converts the current from AC to DC by switching the individual cells on and off at different voltages – one cell on for three volts, two cells for six volts, three cells for nine volts and back down – to create an AC sine wave in real time.

Switching different cells and packs on at different voltages to create the AC sine wave. Image: Relectrify

This is necessary because the electricity inside batteries is a DC current, but the energy running through the grid is an AC current. That means rooftop solar and batteries need inverters to switch between the two, an extra piece of kit which makes both technologies slightly more expensive.

Removing the inverter means they can sell the AC1 at prices on par with cheap Chinese imports – or even lower, Renaud says.

“We’re selling project IRR not upfront CAPEX explicitly as our point of differentiation, in addition to getting more revenue out of the battery, there are safety and reliability and uptime dimensions to the value proposition,” he told Renew Economy.

“But obviously CAPEX is a big part of the equation. So what we’re doing is co-opting all of the economy of scale and efficiency that already exists in the industry and layering our operating system on top of that.

“It’s very hard to be cost competitive, especially with the current dynamic in the market around [manufacturing capacity] oversupply and what that’s doing to pricing in the market.

“But in the end, what we have is a first principles advantage that says the cost of our electronics is less expensive than a conventional inverter and battery management system.”

Renaud believes battery prices, which have plunged since the start of the year, may start to stabilise from now.

Relectrify is aiming at commercial and industrial businesses first, without a need to already have rooftop solar.

“In a perfect world, you’d be coupling directly with on-site rooftop PV, but we don’t view that as a necessary element for a project to be stood up,” he told Renew Economy.

“You can structure a battery on site without solar and still take advantage of and support the solar duck curve dynamics in the market by directly, wholesale exposing the battery through things like the small generation aggregation framework, or through bespoke arrangements through the retail supplier.”

EVs the next frontier

Relectrify grew from a University of Melbourne PhD project in 2015 with a goal to use the operating system to manage battery units made from reconditioned Nissan Leaf batteries.

The idea was to eke out a few more years of life from batteries with 40-80 per cent capacity left.

As ARENA CEO Darren Miller said in a statement, not everything went to plan but the early trials, also supported by the government agency, allowed the company to build today’s operating system.

“What began as a project to reuse end-of-life batteries has now grown into a world-class battery management technology with the potential to transform energy storage,” he said.

The company still has a bank of those in its West Melbourne warehouse to provide backup power, and there are a few still powering businesses in Victoria and New South Wales, and an electric vehicle charging station in New Zealand, one of the first locations where it was tested.

Relectrify’s original Revolve battery from reconditioned Nissan Leaf units. Image: Rachel Williamson

Relectrify is returning to electric cars again, now the hard R&D steps have been done for the AC1 battery.

Today the company says it’s also landed a $2.9 million grant from the Australian Government Industry Growth program to adapt the technology to e-mobility.

It’s a sector that Renaud says includes everything from passenger cars to electric buses, heavy duty mining trucks, and the industrial electrification of distribution centers.

With vehicle-to-grid standards still a non-starter, or at best a work in progress for AC cars, there is a huge amount of work to do to adapt the Relectrify technology to the different power needs of a vehicle and contribute to the evolving tableau of standards.

“E-mobility is a different application. Of course, it has higher demands for power and more rigorous requirements in a number of dimensions,” Renaud says.

“The business model will be a little bit different. It’ll require closer partnering with automotive OEMs to bring the technology to life in a product.

“But the value proposition is clear. The ability to really understand how much fuel is in the tank, the ability to get more range for the vehicle out of a recharge and discharge cycle, the ability to extend the longevity of the battery pack, all those things cut across stationary and mobility.

“But you’re right that the implementation is in many ways more complex.”

Cars with DC batteries are simply energy storage on wheels: it needs an inverter to switch the current to grid-usable AC and therefore allows the charger to handle the often complex and bespoke requirements of the network operator that handles that region.

But a car with an AC battery can plug directly into the grid, meaning that battery and car must be able to recognise and work with the requirements of the network operators covering the area it’s in.