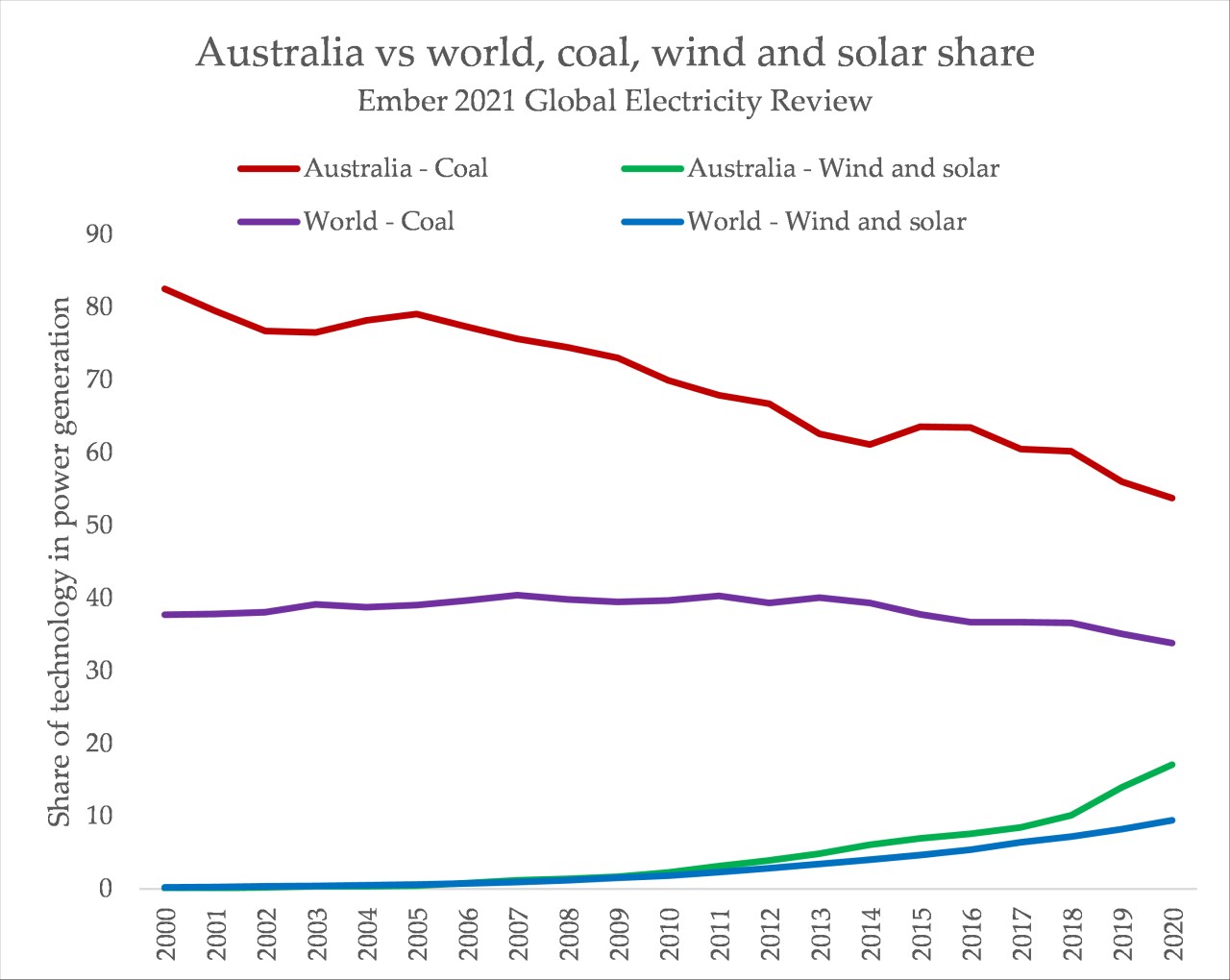

A fascinating duality is emerging for Australia’s power sector. Easily the country’s largest source of greenhouse gas emissions, Australia has simultaneously become a global leader in renewable energy deployment and has also remained one of the worst countries in the world in terms of reliance on coal-fired power. It is a strange, fascinating combination.

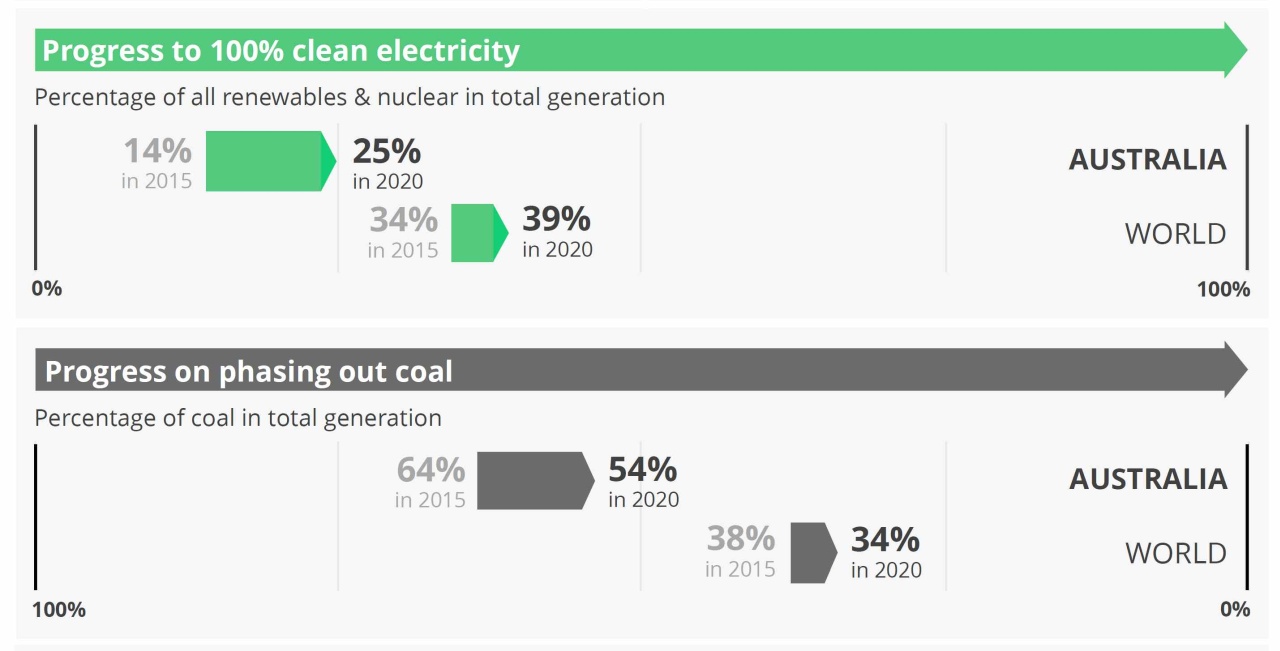

This has been outlined in a new report released on Monday by analytics firm Ember. Renewable energy has grown far faster in Australia than the world average. Wind and solar, for instance, together grown from 7% in 2015 to 17% in 2020. That’s compared to the world average of 5% to 9%. But coal has only fallen 11%, in absolute terms. This is because, of the 29 new terawatt hours of wind, solar and hydro over that time, 16 filled in the gap left by disappearing coal, but the rest simply met growing electricity demand.

“Coal generation needs to be completely phased out in Australia by around 2030 in order to put the world on track for 1.5 degrees”, says a special Australia-focused component of Ember’s report. And gas has remained steady, even though “gas generation also needs to decline rapidly to put the world on track for 1.5 degrees”.

Relative to other countries, wind and solar grew in Australia quite fast. Of G20 countries, Australia ranks third in 2020 for share of wind and solar. Only the United Kingdom and Germany have achieved higher levels (28% and 33% respectively). But Ember also highlight the significant uncertainty in Australia’s near-term renewables growth, as shown in RenewEconomy last week.

The problem is highlighted clearly in the same G20 ranking for reductions in coal. Despite rapid wind and solar growth in Australia, it has one of the smallest percentage reductions in coal in the G20, falling by only 11% between 2015-2020, compared to 51% and 93% for the UK. “Over 40% of the coal fall occurred in 2019, mainly due to a less-than-expected demand for electricity, rather than concerted policy efforts”, write Ember.

In 2020, Ember confirms that Australia has the fifth highest share of fossil fuels in the G20, and the fifth highest share of coal-fired power output. As shown in their data, a big part of the reason is that the ‘middle’ between wind/solar and coal is filled, in Australia, mostly by gas, whereas in other countries, nuclear, hydro, bioenergy and other renewables help push down coal, in addition to wind and solar.

One of the reasons Australia’s new renewables are partly filling in new demand instead of cutting downwards into fossil fuels is because Australia has uniquely high electricity demand, per person. Only Saudi Arabia, South Korea, the US and Canada are worse in terms of per-capita demand (part of the reason Australia’s government tends to use ‘watts per capita’ when insisting enough is being done on climate).

This duality is important. Australia’s growth in wind and solar has been world leading; rapidly departing from the world average. But Australia remains well above the world average in terms of coal. The message for Australia from this massive global comparison project is simple: what has come so far is good, but there is still plenty more work to be done where it counts the most.

As highlighted in Ember’s report, and in the Climate Analytics ‘Scaling up Australia’ report, a program of accelerated coal closure is a key component in increasing the rate of decarbonisation in Australia’s grids. However, with a government hostile towards even the scheduled closure of coal and technologies like wind and solar.

The world is not doing enough

Ember’s report highlights a single over-arching trend around the world – the pandemic has leant suddenly on the pre-existing trend of growing renewables and falling coal, and there’s little clarity if the consequent changes will stay when the pressure of the pandemic is lifted. The change of last year isn’t enough – emissions were still 2% higher in 2020 than the year in which the Paris agreement was signed, despite the impact of the pandemic. Coal must fall by around 14% every year to be on track for net zero by 2050; it fell only 0.8% between 2015 and 2020.

“As electricity demand resumes, the world will need a lot more wind and solar to keep coal falling,” said Dave Jones, Ember’s global lead. “With coal use already rising in 2021 across China, India and the US, it’s clear the big step-up is yet to happen”.

Chian stands out as a unique in both its size and the trend, with rapid growth in both coal and renewables. “China was the only G20 country that saw a large increase in coal generation in the pandemic year. The four largest coal-generating countries after China all saw coal power decline in 2020: India (-5%), the United States (-20%), Japan (-1%) and South Korea (-13%). China is now responsible for more than half (53%) of the world’s coal-fired electricity”, said Ember.

Dr Muyi Yang, Ember’s senior analyst, said: “Despite some progress, China is still struggling to curb its coal generation growth. Fast-rising demand for electricity is driving up coal power and emissions. More sustainable demand growth will enable China to phase out its large coal fleet, especially the least efficient sub-critical coal units, and provide greater opportunity for the country to attain its climate aspirations.”

There remains plenty of mystery about which direction China will actually take on this. But the world’s climate fate is inarguably yoked to the decisions made by a handful of individuals in the halls of power in that country. A country like Australia would do well to add whatever genuine pressure it can by phasing out the burning and export of coal in the very short term.