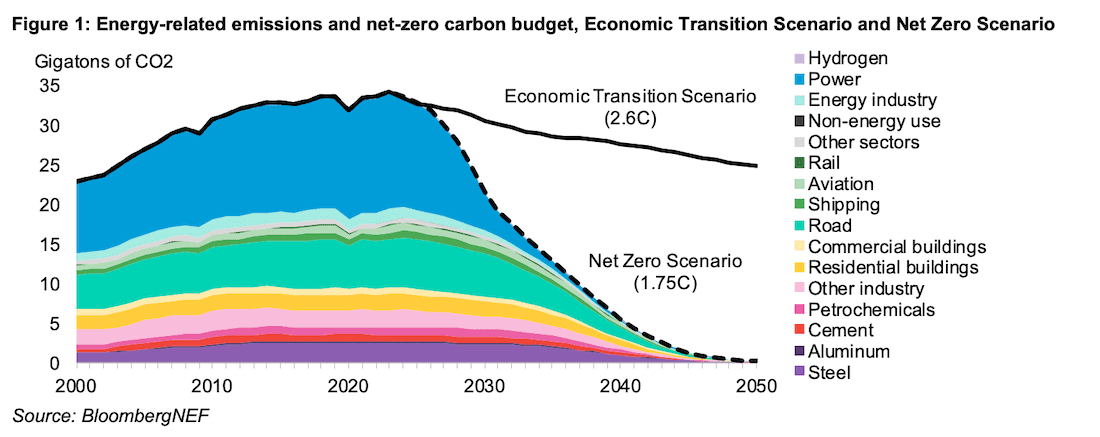

Energy consultancy has abandoned the prospect of limiting global warming to 1.5°C and now says that if the world wants to avoid a 2.6°C hotter environment, fossil fuel use needs to peak and start declining from today.

The company’s 2024 outlook report says the world might be able to achieve 1.75°C warming if a huge ramp up in clean energy technology installations and use happens before 2030, in order to set the stage for continuing gains in the decades after.

“Clearly, time is running out to stay within the global heating limits set by the Paris Agreement,” wrote BNEF deputy CEO Albert Cheung on LinkedIn.

“The Net Zero Scenario, which is consistent with global warming of 1.75°C, requires an immediate peak and decline in emissions from all sectors starting today, and a simultaneous peak and reduction in use of each fossil fuel — coal, oil and gas.

“To get on track for this trajectory, renewable energy must be tripled by 2030, EVs must reach 100 per cent of sales by 2034, and a huge increase in carbon capture and storage (CCS) is needed in this decade.”

The report says every tool – even those like CCS and small modular nuclear which are considered by some to be fringe technologies for present day use – must be scaled up now in order to meet net zero. The other technologies are renewables, EVs, storage, energy grids, hydrogen, sustainable aircraft fuels and heat pumps.

“All nine pillars must succeed if we are to get to net zero – if one falters, another will need to take up the slack,” says Cheung.

It’s a world where EVs are the only new cars sold by 2034 – anywhere in the world; CCS is actually working and handling 3.9 billion metric tons of CO2 (GtCO2) per year by 2030 and 8.1GtCO2 by 2050; green hydrogen dreams for industry and transport have come true with production at 390 million tonnes a year by 2050; and decarbonisation of industry, shipping and aviation becomes a reality after 2030.

“The use of battery-electric planes after 2030 is restricted to small aircraft flying routes of a few hundred kilometres. Hydrogen-fueled narrowbodies enter the market after 2035 and replace half the jet fuel consumed by conventional narrowbodies by 2050. Despite these innovations, over 70% of final energy demand in 2050 is met by sustainable aviation fuel,” the report says.

“Efficiency improvements decrease final energy demand in the shipping sector by 30% in 2050, compared to the ETS. However, low-carbon shipping fuels – including hydrogen-derived fuels such as methanol and ammonia, as well as biofuels – are the only vectors to decarbonise the remaining emissions.

“The shipping industry is therefore facing the prospect of moving from marine bunker fuels to at least four separate fuels in the next few decades during a transition to net-zero carbon emissions, straining global port and refuelling infrastructure.”

Heat pumps continue to be a quiet achiever as carbon budgets for buildings tighten. BNEF predicts that cumulative heat pump installations will triple and reach 507 million globally by 2050 under its net zero scenario.

Bearish on nuclear?

While wind and solar capacity is expected to hit almost 300 terawatts (TW) of installed capacity by 2050, and batteries to touch 4 TW, nuclear is only seen to supply 1 TW of power globally.

The former two are seen to grow by nine times and 50 times, respectively, but nuclear capacity is only seen to triple in the next 36 years, growth which will rely on as-yet unproven technology.

“That will require the lifetime of existing plants to be extended, accelerated deployment in mature and fledgling markets, and rapid development of small modular reactors (though these SMRs play a small role due to their higher costs compared to conventional reactors),” the report says.

“Nuclear plant additions are concentrated in Asia Pacific, accounting for two-thirds of global capacity additions, driven by the need to meet rapidly growing power demand.”

The report forecasts nuclear power to play a relatively small although important role in decarbonising grids in China, India, Southeast Asia, the US, Japan and South Korea, with Australia and Latin America remaining out of the game entirely.

More money needed

The investment needed to limit warming to 1.75°C is also rising inexorably, to $US5.4 trillion ($A8.1 trillion) every year until 2030.

Last year, BNEF noted that $US1.8 trillion was spent on low-carbon technologies.

Significant funding needs to be ripped out of fossil fuels, with investment shifting from parity today to spending that is 3:1 in favour of clean tech.

That works out to $US2.7 trillion annually going into clean energy and just $US0.9 trillion into fossil fuel energy generation.

BNEF’s new base case is for renewables to make up 70 per cent of electricity generation by 2050, a scenario that will lead to circa 2.6°C warming.

But if the world lifts transition budgets by 19 per cent to $215 trillion ($A322 trillion), it could decarbonise energy systems completely.

Flexibility is key to bringing it all home

Pulling all of this together is system flexibility, which will be built around demand response, interconnection, flexible ‘peaker’ plants, pumped storage, and smart EV charging.

“The most substantial sources of flexibility in the ETS are batteries and smart EV charging, which shift about 2,900 and 3,000 terawatt-hours of energy in 2050, respectively,” the report says.

But whether the world does nothing more from today or continues with current decarbonisation plans and fails to reach net zero, BNEF is calling the end of fossil fuels, saying that in its base case gas is increasingly replacing high-cost coal in the power sector in Asia Pacific while oil hits a demand peak in 2028-29, as transport electrification destroys demand.

“Even if the transition is propelled by economics alone, with no further policy drivers to help, renewables could still cross a 50% share of electricity generation at the end of this decade,” it says.