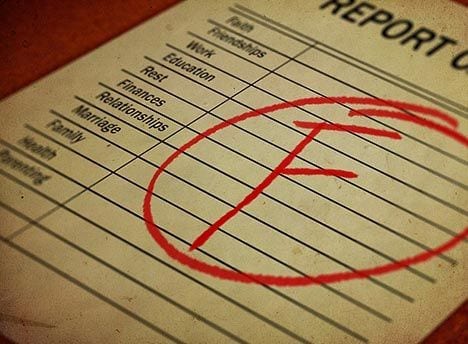

A global report card has marked Australia’s climate action with swathes of red ink, saying the country has not only increased fossil fuel subsidies but gone backwards on climate-risk disclosure policies.

BloombergNEF’s Climate Policy Factbook paints a dire picture of where Australia sits as a climate actor ahead of COP27 in Egypt, and suggests a combination of a muscular new government and government bodies’ nervousness about climate risk will lead the way up.

The report card covers fossil fuel support between 2016-2020 when Australia’s spending on fossil fuel subsidies rose by 4 per cent and totalled $US38 billion ($A59.2 billion).

In 2020 alone, OECD data shows the country spent $10.6 billion on those handouts, a figure that could double in 2021 once election year promises and compensation payments to coal and gas power plant operators are factored in.

Most of this came in the form of tax breaks such as capital spending deductions for mines, fuel tax credits and smaller fuel excise rates on diesel vehicles.

BNEF estimates Australia lost $US6 billion from fossil fuel tax incentives alone.

“The chances of bold climate action by Australia’s federal government have improved significantly in the last year, after the Australian Labor Party took power for the first time in 10 years in May 2022,” the report said.

“But unlike other Annex I parties [industrialised countries], Australia is unlikely to sign up to ambitious pledges to phase out coal-fired power.”

New government gains higher marks

The report noted the new federal government’s swift moves to pass 2050 net-zero legislation, a 43 per cent emissions reduction by 2030 from 2005 levels, and efforts to incentivise decarbonisation in transport and industry.

And the government also won a credit for moves to overhaul the Safeguard Mechanism, the system that regulates emissions from 215 of the country’s biggest polluters via a baseline and credit process where industrial companies surrender offsets if they breach set emission levels.

The government plans to reduce the emissions baselines and reward companies if they consistently get their emissions under that level with a new form of Safeguard Mechanism Credit (SMC) that can be sold or banked against future baseline breaches or obligations. A draft bill is due in December.

Climate risk disclosure is an increasing concern for Australia’s regulators.

BNEF notes Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) reporting isn’t compulsory, but encouragement from corporate cop ASIC to use the UK-designed reporting system and increased scrutiny by APRA into climate risk management could spur this sector along.

Globally, could do better

The COP27 meeting in Egypt will focus on how countries have gone about achieving targets around phasing out fossil-fuel subsidies and supports, pricing carbon emissions and implementing mandatory climate-risk disclosure for investors.

Globally, the world hasn’t done particularly well.

G20 government support for fossil fuels was at its highest level since 2014 at $US693 billion, driven by retail energy price subsidies, tax breaks and budgetary transfers.

Of the mere six countries that pledged last year to phase out coal power, five increased their reliance on the form of power.

Carbon pricing is one area of partial success. The BNEF report says Canada, Indonesia, Russia, and the US implemented new taxes or markets for carbon pricing; South Africa lifted tax rates, Australia started reforms, and India started to think about it.

But as the effects of climate change are becoming increasingly obvious in terms of dangerous weather, policymakers are also worried about related risks and their impact on financial stability. BNEF criticised the light touch, not regulated manner government’s are going about this to date, saying it gives financial institutions too much wiggle room.