The listed gas infrastructure company and power producer APA Group has – in just a few hours of analyst presentations – highlighted the impossible dilemma facing Australia’s gas industry: How to put on a brave face for the future when its own research shows its current strategy is stuffed if the world takes climate action seriously.

APA had a double announcement on Wednesday, the release of its full year results and its new climate plan, which outlined how it was moving to “net zero” by 2050, and that it intended to buy only 100 per cent renewable power from 2023.

The basic thrust of its argument was this: Gas has a critical role to play in Australia’s transition to renewables. But its detailed assessment of what a 1.5°C climate scenario looked like painted a completely different picture. Gas, at best, is a short term option, which surely must question its plan to invest billions in new infrastructure.

Rob Wheals, the CEO who announced his resignation earlier this week, described gas as the “ally” and “companion” of renewables.

“Gas is the ally of renewable energy, and will support the addition of all intermittent energy sources,” he told an analysts briefing. “Put quite simply, gas generation is the key ingredient to help Australia fast track the energy transition.”

Wheals says this supports the push for more gas production in massive “frontier basins” in the north of Australia and the infrastructure to connect it.

APA is already investing in numerous gas pipeline additions and expansions in the current gas grid in NSW and Victoria, but its own climate report, which boasts of a targeted 30 per cent cut in emissions by 2030 as part of its efforts to cap global warming, questions the wisdom of that.

First, there is the question of how much gas will be needed in the main grid. Wheals noted that AEMO’s Integrated System Plan assumes a nine-fold increase in large scale renewables and a three fold increase in storage, but only a 20 per cent increase in gas capacity.

And it is important to note that this is gas capacity, not generation. The amount of gas burned is likely to be considerably less because gas generation will only be used as a peaking plant to fill in the gaps, even at the Diamantina gas generator in Mt Isa, where the company is also building the 88MW Mica Creek solar farm.

As APA notes elsewhere, it’s all dependent on the climate outcome. Under a 1.5° scenario, it says in its presentation, “baseload to be provided by renewables (solar, wind), supported by storage technologies with limited role for gas firming.”

As for gas demand itself, it notes: “Domestic gas demand to fall rapidly (down ~40% by 2040), led by decrease in residential and commercial demand, with GPG falling due to shift towards renewables.”

And it’s not much better on the global front in the 1.5°C scenario: “LNG prices are suppressed due to low global demand,” it says. “Decline in LNG export volumes from 2030.”

That’s in APA’s own words, hardly a ringing endorsement of investing billions in assets that should have lifespans of many decades, yet it continues to advance the gas infrastructure investment because, according to Wheals, they can’t be sure where the climate outcome is going to end up.

If the gas industry has its way, it sure won’t be 1.5°C.

Here’s some other interesting graphs from the APA climate report.

The first is from their own climate commitments.

The commitment to 100 per cent renewable electricity sounds grand, but is restricted to corporate needs, so it won’t be much in practice and only accounts for 10 per cent of their 30 per cent emission reduction goal for 2030.

Another 10-20 per cent comes from the electricity used to compress the gas for the pipelines, and another 30-40 per cent from detecting and managing methane leaks. You might have thought they were already doing that.

The other 35-45 per cent comes from “opportunities yet to be evaluated” – which seems a bit weak for a detailed climate study and a modest target, and the inevitable “offsets”.

Because of its mix of gas generation and 460MW of renewables (it owns the Darling Downs solar farm in Queensland, and the Emu Downs and Badingarra wind and solar farms in Western Australia), it has a relatively low emissions intensity (see table above).

It seems to suggest that it won’t be able to do much more. The graph above on the right shows the overall grid catching up to it by 2030. APA’s emissions tail off from there, but it would have been interesting if it had extended the AEMO step change scenario out to 2030.

Wheals did concede later in the presentation that the company would need around another six Mica Creek solar farms (the 88MW facility it is building in the Mt Isa grid), to cut its emissions. But it wasn’t clear if that was a plan, or just a description of the task at hand.

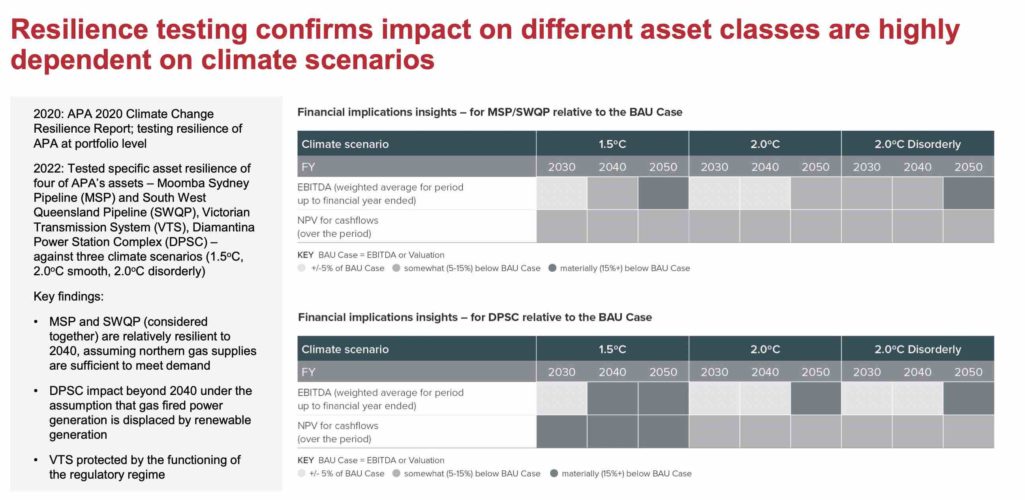

As to the future health of some its assets, it is clear they look better in a 2°C scenario than a 1.5°C scenario.

This graph shows the Diamantina gas generator running into trouble by 2030, and clouds starting to form over the the major Moomba Sydney pipeline around that time too.

And, given the growing push for electrification, and the increase scrutiny over methane leaks, it seems less clear that the future of gas infrastructure is as grand as the industry makes out – unless, of course, they are protected by regulatory fiat, in which the consumer and the taxpayer can foot the bill.