Energy experts are still scratching their heads about what they could have done to prevent the massive, state-wide blackout that occurred in the midst of a one-in-50-years storm last month. The answer may lay inside South Australian homes. Or at least, it should do. And it’s battery storage.

Dean Spaccavento, the CEO of Australian energy management software company Reposit Power, says battery storage placed in thousands of homes in Adelaide and the surrounding region – and linked through smart software – could have provided the emergency supply to help stabilise the network at its moment of crisis.

In a matter of seconds, the interconnector became overloaded as it made up for lost power on the South Australia network following the catastrophic series of events that saw three of the main transmission lines disconnect as pylons crashed to the ground.

Battery storage, Spaccavento says, could have provided the emergency system back-up. “That would have stopped the cascading dominoes,” he says. And not a lot would have been required.

To provide 50MW, possibly enough to prevent the Heywood line from going over its overload capacity, the number of homes with linked battery storage would have to have been around 12,500. If the amount needed was 250MW, then it would have required 50,000 households. Around 200,000 households in the state already have rooftop solar.

Reposit Power’s comments are timely, given that the state and federal energy ministers are meeting tomorrow, and on their agenda is a report from the CSIRO about battery storage.

Hopefully, it will be a little more up to date than the AEMO chairman’s report at the last COAG meeting a few weeks ago, when he said that battery storage would not be competitive for up to two decades.

ACT energy minister Simon Corbell found those comments remarkable, and wrong. And as David Leitch writes in this analysis (and advice to federal energy minister Josh Frydenberg advisors) battery storage may already be commercial. Certainly, some networks think so.

Indeed, Reposit Power has written a letter to the ministers asking them to consider the role this aggregated clean energy system plays in keeping the grid balanced.

Reposit’s COO Luke Osborne said “Australian households can provide a cheap and bullet-proof solution to ensuring Australia’s future energy stability.”

The idea that storage could have helped avoid the crisis is not new. AGL, which operates the biggest gas generator in the state, said earlier this week that the best way to offer energy security was through distributed generation and storage and micro-grids, and this could only happen with renewable energy.

That’s the trick with battery storage, to unlock its value streams; no easy task in a grid designed to operate with decades old technology and even older thinking. AGL is having a go, by trialling a scheme that links household storage to make a “virtual power plant”, and SA Power Networks is conducting trials of its own.

The attraction is that much of the investment for battery storage would come from the households themselves, although the government might want to consider subsidies to reduce the cost.

Providing these services – responding to peak demand and providing emergency back-up, can add to the revenue stream of the battery owner, over and above the time shifting they use for their rooftop solar.

In a briefing Reposit Power wrote for Senator Nick Xenophon, Spaccavento said system security would be increased with each added (linked) battery, and it would mean added value to households and increased private investment in the grid.

“Scaling of this business model will solve South Australia’s grid instability,” the briefing said. But it said initiatives, such as the ACT government’s “Next Gen” battery storage program, would accelerate the uptake and help overcome market barriers.

Transmission lines fell, some wind farms lost output, more than half of the state’s gas capacity was offline or unavailable, or simply too slow to respond. And when the interconnector became overloaded, it too disconnected.

What an energy market operator needs most of all in a crisis is time. The interim AEMO report shows that the crisis played out in less than a minute, the most dramatic events occurring in the space of a few seconds, or even fractions of seconds.

That’s what makes battery storage so attractive. It can respond in milliseconds, providing network support, or outright power – sometimes for only short periods of time. But quite possibly enough for the operator to marshal its defences and get slow-moving gas generators online and other support.

Spaccavento points out that battery storage could not be expected to power the state for any lengthy period. It is designed to hold the system steady for a short period of time so the operator can look at other long-term solutions.

“On September 28, we don’t know what happens next. But storage could have given the operator time to find another option,” he told RenewEconomy.

One of those options could have been creating enough time for the unused gas generation to ramp up and provide more capacity, reducing the load on the interconnector. Although, frankly, there was no of knowing what the impact of the transmission lines would have been.

Spaccavento says, however, that the grid had held up remarkably well considering what was thrown at it.

“This was pretty much a power system apocalypse,” he said. “It’s amazing that it stayed (online) as long as it did. The state got torn apart.” And, he noted, it was interesting that no wind farms tripped, and most of their capacity was still there until the interconnector failed and all generators tripped at the last moment.

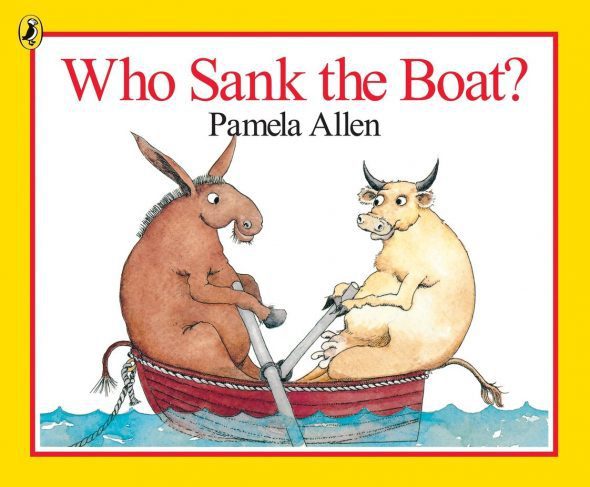

Osborne compares what happened in South Australia to the children’s book “Who sank the boat”. That’s when “a cow, a pig, a donkey, a sheep and a tiny mouse go for a row, but one of them sinks the boat.”

The mouse is blamed because it was the last one in. It was kind of what happened in South Australia – it was the last 50MW strain on the interconnector that eventually ended all resistance, and the system sank.