Oh dear. Here we go again. The solar industry is clearly winning the battle to turn the global electricity industry upside down and inside out. The plunging cost of battery storage will accelerate that process. It’s just that some people have a hard time accepting it.

This week we have seen another big report into solar, and yet another that gets it terribly wrong.

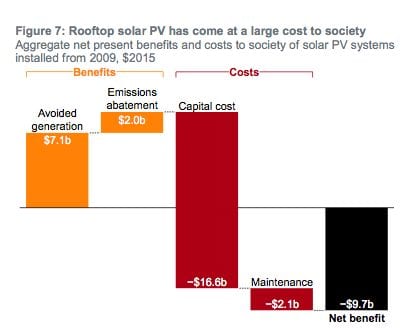

“Solar homes burnt by the sun”, wrote Fairfax Media, and others followed. Predictably. But Why? Because the Grattan Institute wrote in a report that the economic costs of rooftop solar outweighed the benefits by more than $9 billion.

If Grattan’s goal was to secure big headlines, let’s give it a credit. But to achieve it, it had to concoct a witch’s brew of mistaken assumptions and omissions.

That’s a shame. The conclusions it makes at the end of the report and its recommendations on how to incorporate the inevitable surge in battery storage are important, even if not terribly new.

But they will be obscured by the numbers that have and will be used like confetti by those seeking to restrain the deployment of solar PV in an attempt to protect vested interests.

The numbers it uses are wrong in so many ways it is difficult to know where to start. But because it got the headlines, let’s start with that $9 billion figure.

Grattan Institute argues that the cost of solar PV ($18 billion) overwhelms the benefits ($9 billion mostly in avoided generation costs, and a little in avoided emissions), and it further suggests that individual households are getting little bang for their buck from their individual systems

The first thing it gets wrong is to base its report on the assumption that solar systems only last for 15 years. Most solar systems are likely to last 25, or even 30 years. Some even more. So from the outset, Grattan has underestimated the benefits in avoided grid costs and abatement by at least 40 per cent. That’s a critical number that delivers an entirely different outcome.

And then – like so many other reports – it adds up the costs, but not all the benefits. In this case, it dismisses the lowering of wholesale electricity prices caused by the proliferation of solar PV, which, it argues, “does not constitute a net economic benefit to society”.

Instead, Grattan borrows terminology from the Warburton Review to describe this lowering of wholesale prices as a short-term financial transfer from “existing generators to electricity retailers” who may then pass these savings onto consumers.

Well, it just happens that most of those existing generators and electricity retailers are one and the same entities – hence the name “gentailers” (Origin Energy, AGL Energy, EnergyAustralia). If they are pocketing the profits, it’s the incumbents with their hand in the till, not the solar households, and a regulatory fault.

And there is no doubt that wholesale prices have fallen. The Queensland government’s biggest coal generator, Stanwell Corp, blamed solar PV exclusively on its inability to deliver a profit result in 2013.

Green Energy Markets, in late 2013, estimated the cost reduction from solar PV at $2.70/MWh. Spread over a year that amounts to $540 million in savings (based on the 200TWh consumed in the National Electricity Market). Spread over the 15 years used in Grattan’s calculations, that amounts to $8 billion.

But the University of Melbourne argued that the savings were even greater. It suggested that rooftop solar PV could be responsible for a reduction of $2-$4/MWh in average price per 1,000MW across the NEM. Given that there is now nearly 4,000MW of solar PV installed in the NEM (that doesn’t include WA), then the savings per year could be $2 billion. Over 15 years, that makes a total of $30 billion.

Those falls in wholesale prices do find their ways through to the general market. It explains why some major energy users – data centres for banks for instance – pay a price of just 8c/kWh. That’s one-quarter what the average household pays. The same experience can be said of Germany, which now delivers some of the lowest costs of electricity to big business, because of the fall in the wholesale price.

That cross subsidy, from homes to business, is just one of many that exist in the Australian market.

Not only do households pay higher bills than businesses, people in the city pay more to offset the cost of delivery to regional areas. In Queensland and Western Australia, this amounts to $600 million a year in each state. Over 15 years, that’s a total of $18 billion. If those subsidies were removed, there would be an incredibly powerful economic incentive to install solar, storage and micro-grids, as some networks suggest.

Another juicy, but largely ignored subsidy is the so-called “head-room” for retailers. This is the kitty used by the retailers to offer “discounts” to consumers. In NSW, this headroom costs around $140 per consumer – or a total of around $140 million. It’s bit into their power bills, just so the retailers can offer a discount to neighbours.

Grattan says that the cross-subsidy in the various solar schemes amounts to $14 billion. There is no doubt that those schemes, mostly wound back several years ago, were more expensive than they needed to be. Former Queensland Premier Campbell Newman doubled the cost of the most expensive scheme, the Queensland premium feed-in tariffs, by giving six weeks notice of its closure, inviting tens of thousands to join at the last minute.

The Australian PV Institute says Grattan’s estimates do not take into account the fact that all mainland distribution network operators (DNSPs) in the NEM, apart from in Queensland and since July, 2014, in NSW, operate under a weighted average price cap (WAPC).”

This means that the fall in revenue driven by reduced electricity use is actually borne by the DNSPs, not by customers as Grattan says. This applies to $3.7 billion of their costs to customers. (See more of the APVI analysis here).

And the benefits of some of those subsidies, the small-scale renewable scheme went to the retailers, not solar consumers. That was because the retailers were allowed by all pricing regulators (with the notable exception of the ACT) to charge $40 for every certificate even when the market price was little more than half that.

Grattan goes on to talk of the cost of network upgrades. This, again, is a little one-sided. As SA Power Networks has said, solar PV has not only shifted, narrowed and capped the peaks (the same has happened in Western Australia); it has also added stability to the grid in the summer heatwaves. EnergyAustralia says soalr PV accounts for 25 per cent of demand at peak times, which in any case varies enormously from summer to winter, north to south, and east to west.

Grattan takes a similarly narrow view in its estimate of emissions abatement costs. It puts these at $170/tonne of avoid emissions, and then compares them unfavourably with other carbon prices. But again this ignores the longer life of the solar systems, and the fact that three times as many systems will now be deployed in Australia, with few if any subsidies.

And that forms part of the broader benefits not included in the Grattan report. Yes, initial subsidies were more expensive than they needed to be, but Australia now has the cheapest solar PV anywhere in the world, and the reductions in the wholesale price and the emissions abatement will continue.

And that benefit will be amplified when battery storage becomes available – as it will do in a matter of weeks when AGL Energy rolls out a plan to put batteries on customer rooftops at no upfront cost (apart from signing up for a very long power purchase agreement).

As Muriel Watt, from the APVI, told RenewEcoomy: “All the supposed negative impacts on the network, if they exist, are likely to be reversed when batteries come in, and PV households will be the first to install them, potentially making the grid much stronger, if the utilities provide the right incentives.

“Why not have headlines which say the investment people have made in PV is soon to provide billions in benefits to all consumers, because adding storage provides a much more resilient power system?”

And this is the crunch. When this happens, solar PV, with battery storage, will be even more effective in reducing or even eliminating the peaks. So much so, that some analysts say that the business case for peaking gas generators – the equipment we usually use at great cost when everyone switches on their air-con at the same time – will lose their economic base.

Grattan also has a crack at costing a move off-grid, arguing that it would be horrendously expensive. Its costings of technology are highly debatable, but it misses an essential point.

It assumes that the individual households motivated enough to go off grid will make the same fundamental error that the grid made these past 10 years, creating a 20 lane highway that is needed for only a few hours a year, when a two lane highway will suffice for most of the year, and a 10 lane highway at peak times.

“From my 20 plus years of experience designing and building energy systems for off-grid homes, I find they typically have energy footprints of half or less of their on-grid cousins,” says Glen Morris, from the Australian Energy Storage Council, and one of the foremost experts in the country.

“Appliances are just getting better and better – take air conditioners, hot water heaters, even cloths dryers… their energy savings have been in the order of 3-5 times their predecessors of ten years ago.” Indeed, Morris says buying an efficient fridge might cost an extra $1500, but it is likely to save $15,000 in infrastructure costs. In this, households are learning lessons that the grid operators never did.

Grattan’s numbers look strange for other reasons. It contrasts a household’s grid costs of $1300 a year (they must not use much electricity) with a total off-grid cost of $72,000, with a 15kW solar system and 85kWh of storage. That means they must be using lot of electricity, and make no allowances for changed usage.

That has been the underlying cause of the massive over-investment in the grid, and the economic opportunity for solar and now battery storage. And it is much easier for a household to adapt their energy consumption to work around those peak periods, or when the supply is low. It is even easier for a small community of off-grid homes to do the same. Hence the push to micro-grids. No big networks or retailers needed there.

The headline numbers in the Grattan report are little more than scare mongering. And the industry, one hopes, has moved on. The signs are already good. Network operators talk of a future dominated by solar and micro-grids. Even the retailers are getting on board.

Where once AGL energy demonised solar tariffs as a “scam”, it is now offering to buy a solar system for its customers and stick it on their roof. AGL will even buy you a battery system. Where once Origin once called solar households “free riders”, implying they were stealing from their neighbours, now they are urging customers to use their rooftops to “steal from the sun.”

Solar has won. Storage will see to that. It’s just that some people don’t know it yet. The onus is on the energy industry to be smart about its response, and not rely on dumb economics.