Last month the Australian Energy Market Operator released an update to the latest ESOO – a document that intends to inform planning and decision-making for new investment in the NEM.

In perhaps a sign of the times, 48 hours later the report and its modeling became partially outdated with the announcement of an extension to the was-soon-to-be-retired Eraring Power Station, the largest station in the NEM.

The updated document superseded the original report released nine months prior, and highlighted significant delays to major projects while simultaneously reporting the inclusion of 4.6 GW of sufficiently advanced projects over a longer time horizon.

In this article, we seek to identify the most intriguing projects that have changed status between the two versions of the ESOO. Hopefully, this will help our readers ponder the state of the project development pipeline, and the modelling that relies upon it.

What’s changed?

For context, the AEMO has three general categories in which they classify the status of new projects. These projects are assessed based on their procurement progress against five key criteria (land, contracts, planning, finance and construction). At a high-level, these three categories are:

Committed – Projects that will proceed as they satisfy all five criteria. In some cases, projects are marked as committed but with an asterisk if they satisfy land, finance and construction criteria, and are in the process of finalising either contract or planning obligations.

Anticipated – Projects that meet at least three of the five criteria. If the developer does not submit survey information back to the AEMO at least once every 6 months, the project is bumped back to ‘publicly announced’ or withdrawn from the database.

Publicly Announced – Projects that have been announced/proposed by a developer. These do not necessarily need to meet any of the five key criteria. The ‘likelihood of proceeding’ of the projects within this category varies significantly.

Delays

Let’s start with identifying which projects have been delayed since the original ESOO 2023 in August. Colin Packham of the Australian recently reported that 15 of 76 new projects faced delays, by his count, since halfway through last year.

Below I have attempted to put together my own list tracking down each of these delayed projects. In order to compile this list I’ve had to navigate and scrape various archived versions of the Generation Information Spreadsheet maintained by the AEMO.

As others may have experienced, the spreadsheet is not the most user-friendly or dissectable dataset, especially for longitudinal analysis. I will elaborate on why that may be an issue in a follow-up Part 2 of this analysis, but in the meantime, if you spot any omissions or errors in the table below, then please leave a comment.

As almost half of those generation projects are storage, it is worth noting:

– With respect to big batteries, we recently published an analysis examining the actual development timelines for each of the existing twenty big batteries in the NEM. The second graphic in that article highlighted that the nine most recent BESS projects had taken from 16 up to 26 months to go from financial close to full operations.

– With respect to pumped hydro, the shifting expected completion date of Snowy 2.0 has been well publicised. This is perhaps a lesson that anticipating a completion date for a project of that size and complexity is difficult.

Leaving the market

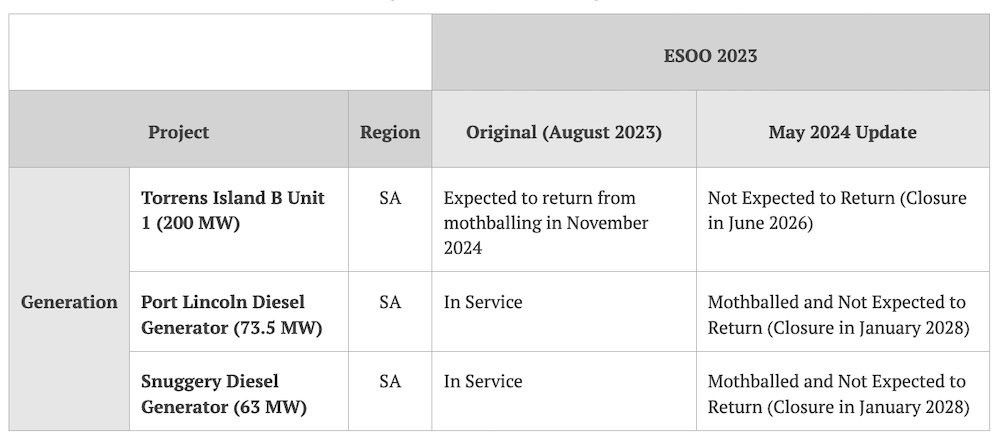

In addition to the announced two- to four-year extension of Eraring, announced two days after the release of the ESOO update, it was announced that three units will be leaving the market since the original ESOO.

Newly progressed capacity

The ESOO update highlighted that “4.6 GW of new capacity had advanced enough to be considered” within their modelling.

I won’t list these in this article but hope to cover each of these projects in Part 2 in coming weeks.

A slightly longer view of development

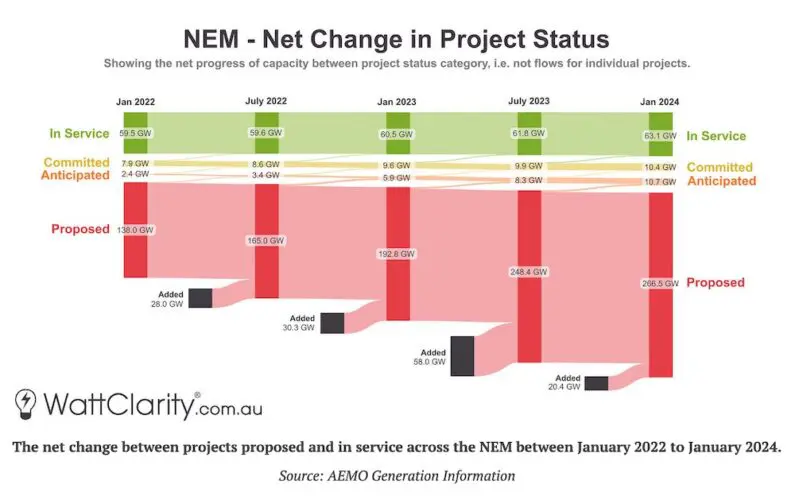

Below is a simplified Sankey diagram I’ve created using archived versions of the AEMO’s Generation Information spreadsheet. The diagram does not track flows of individual projects as some projects occasionally get withdrawn, have their status bumped back, or can skip steps – but rather, the diagram tracks the net change in flows from the four project stages.

As time permits I’ll endeavour to update and expand upon this diagram in future articles, but for now, two key points stand out:

– It’s clear that the amount of capacity ‘In Service’ and at the ‘Committed’ stage has largely stalled. If we consider just the capacity losses from eventual coal retirements, it’s hard to see how a net gain of 2.5 GW of new project commitments over a two-year period is keeping up with the speed of the transition.

– The sheer volume of proposed projects dwarfs the number actually being progressed. Perhaps others more knowledgeable than myself could provide insight (via the comment section) as to whether this may be causing bottlenecks in itself? And their thoughts on whether this is an efficient allocation of resources and skills in terms of addressing the biggest problems in the energy transition (an honest question, not a statement).

As the Australian reported last week, some industry executives have suggested that the incoming Capacity Investment Scheme may even further strangle development progress in the short-to-medium term, as developers face more variables and complexity when evaluating their bid parameters.

Key Takeaways

As time permits, I will publish a second instalment of this analysis, but from Part 1 today I’ll finish with a couple of takeaways:

– Projects already committed and anticipated continue to face delays. A significant number of these delays relate to storage projects. In that regard, it is a much different development environment from the ‘100 days or it’s free’ promise that Elon Musk delivered seven years ago.

– We may be building anticipation faster than we’re actually building new projects. The disparity between the volume of proposed projects and those advancing through to completion should perhaps raise some concern about a ‘perception vs reality’ dilemma.

This article was originally published by Watt Clarity. Republished here with permission. Read the original version of the article here.