Today, the Climate Council has released a detail report explaining why it believes that achieving a 1.5°C climate target is now impossible. It does point out that with strong, immediate and wide scale action, it is still possible for Australian to provide plenty of global momentum towards limiting the Earth’s temperatures to less ambitious goals. The report suggests that the 2030 emissions reductions target should be 75%, and that net zero emissions should be achieved by 2035 (as suggested by many of the same scientists in January this year)

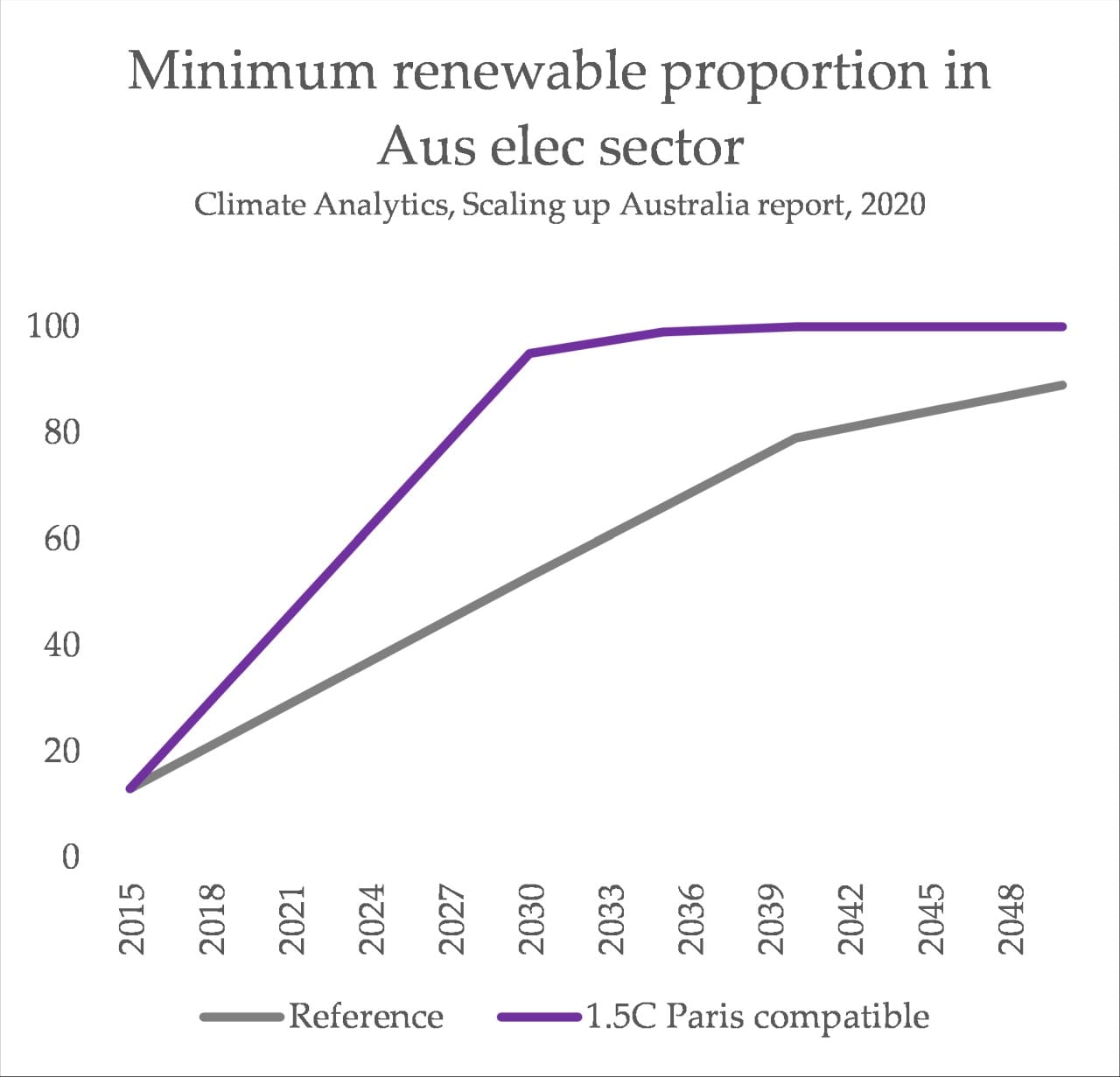

That means achieving nearly 100% renewable energy by 2030 – something suggested by a range of other analysis, such as Climate Analytics’ Scaling Up Australia report. The most recent projections from the Australian government suggest Australia is on track to hit barely 50% renewable energy by 2030.

These reports come right as the rumour mill is making noises that Prime Minister Scott Morrison is likely to announce a ‘net zero’ target, either during the US climate summit next week or sometime prior to the November COP26 global climate summit. That’s been paired with what seems to be like a fairly serious effort to convince the world that Australia is, pinky promise, really getting its act together on climate change.

What has become extremely clear about net zero targets is that while they are a vital core of global climate policy, they are also full of various loopholes that are yet to be shut closed. That means Australia could easily set a net zero by 2050 target without changing a single thing about its existing climate trajectory.

Here are some ways that the Morrison government would try to water down a net zero target while soaking up accolades for establishing it, with plenty of inspiration taken by this recent piece in the scientific journal Nature.

Delay the date

China’s net zero target is 2060. Though its emissions are currently comfortably the world’s highest, historically it has not been the largest emitter in cumulative emissions terms. Australia has – and therefore it ought to decarbonise far earlier. It’s a perplexing nuance of ‘fair share’ between countries, and Morrison could happily exploit that to set a ‘net zero by 2060’ target. This would be a specific reversal of the principles of fairness and equity in the Paris agreement.

Exclude greenhouse gases or sectors

Various substances cause climate change. Carbon dioxide (the big one), methane, nitrous oxide et al – these are known as ‘greenhouse gases’. Some climate targets only include the carbon dioxide part, others include some or all of the other greenhouse gases. It’s exhausting, but that’s the point – and by excluding non-carbon gases, Morrison would be giving a free pass to his cherised gas industry. Ditto for excluding sectors, such as the recent suggestion to not include the agriculture sector.

Aim low

Some net zero ambitions are calculated around temperature targets in different ways. For example, one could target ‘stabilising’ at 1.5 degrees, but allowing for a temporary overshoot. Others make that a hard limit. Morrison could happily set the weakest combination of this, perhaps justifying on the grounds that climate scientists declare the more ambitious ones “impossible”. It would be buried in the fine print, and this justification would be true in the sense that some scientists do now describe high climate ambition as “impossible”.

Rely on removals

Many of the worst net zero plans avoid laying out any serious, short term emissions reductions by assuming a heavy and ludicrously overblown role of ’emissions removal’ in the final decades prior to 2050. This means planting more trees, or using technology to suck carbon from the air – technology that remains mostly not yet invented. While it works on paper, it’s a near-guarantee of failure.

Avoid milestones

In the UK, the net zero target isn’t about 2050 – it’s about now. An independent government body called the Climate Change Committee (CCC) just laid out the ‘sixth carbon budget’ – an extremely short term plan that sets clear boundaries for emissions and outlines the changes that need to happen right now. This is the precise antithesis of Australia’s climate policy, which is, very literally, a PDF that sets out a few nice-sounding technologies. The creation of a separate body that would hold the government to account on a net zero target seems improbable; just as improbable as the government adjusting their 2030 target to align with a net zero by 2050 goal.

What is becoming increasingly clear is that the ‘net zero’ framework provides far too much wiggle room. There are hundreds of companies and countries that have created and written a target, but avoided any real substance. Morrison and Taylor will be far behind the curve on this, if they choose to establish a weak, empty net zero ambition. So far behind, in fact, that the reaction – in which people became far more critical of glossy announcements and dodgy ambitions – has become mainstream.