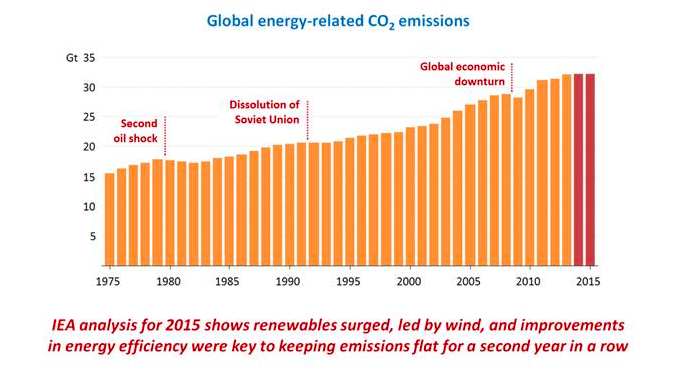

First, the good news. According to the International Energy Agency, energy-related carbon dioxide emissions stayed flat for the second year in a row in 2015 – a clear sign that the nexus between economic growth and increasing energy emissions has been broken.

The IEA says that the two biggest economies and energy consumers, the US and China, both achieved significant cuts in the last year (by 2 per cent and 1.5 per cent respectively), as coal-fired generation was replaced by gas in the US, and by wind and solar and energy efficiency in both countries.

And the world can do more, says the International Renewable Energy Agency. By doubling its capacity in renewable energy – principally wind and solar – by 2030, the world can keep on track to meet its Paris climate targets, save $4.2 trillion in fuel, boost its GDP by $1.3 trillion and generate some 9 million jobs. Too easy.

And the world can do more, says the International Renewable Energy Agency. By doubling its capacity in renewable energy – principally wind and solar – by 2030, the world can keep on track to meet its Paris climate targets, save $4.2 trillion in fuel, boost its GDP by $1.3 trillion and generate some 9 million jobs. Too easy.

But here’s the bad news. While the world’s two biggest emitters are managing to bring their energy emissions under control, those of Australia are continuing to soar – by around 4.5 per cent since the Coalition government dumped the carbon price nearly two years ago.

Coal generation, declining in US and China, is rebounding in Australia. Large-scale renewable energy investment has come to a complete standstill under any policy over which the Coalition government has control.

Indeed, it is nearly a year since a compromise deal was reached on the large-scale renewable energy target – cutting it from 42,000GWh to 33,000GWh, and more than six months since Malcolm Turnbull raised hopes of a turnaround when he became prime minister.

Turnbull declares himself entirely satisfied with the status quo, possibly encouraged by the fact that while 47 per cent of people say that climate and clean energy policies might influence their vote, more than half say it won’t.

“We have effective and responsible climate change policies that are working,” Turnbull told parliament on Wednesday. “We are on track to beat and meet our 2020 emission reduction target. Our 2030 target is responsible and in line with that of comparable countries.”

Turnbull was speaking in response to a question from Greens MP Adam Bandt, who asked if Turnbull agreed with the assessment of chief scientist Alan Finkel, who on the same day that new data showed a stunning rise in average global temperatures, said that under current policies we are losing the battle against climate change?

Turnbull responded by doing a passable, if less succinct, impression of his predecessor, Tony Abbott.

“We are transitioning from an old economy or an older economy to a new one – a 21st century economy, one that is grounded in innovation, in technology, in competition – and every lever of our policy is pulling in that direction.”

Turnbull then said that the government was “reducing emissions with our Emissions Reduction Fund” (which is not true), and “promoting energy efficiency and clean energy innovation; and we are investing in large-scale renewable energy, particularly large-scale solar and storage” (which is only happening via agencies that the government says should be dismantled).

Turnbull’s inaction in climate speaks of the lingering influence of the hard right in the Coalition and the delicate politics of ditching Abbott-era policies. But it is not clear that Turnbull, even if re-elected, would shift his actual policies to the more moderate position that his rhetoric suggests.

What the Coalition government – in fact all mainstream parties – have failed to understand is that coal is effectively dead, as a current or future investment. China and the US have used the power of regulation to throw their coal industries into reverse, and the world’s biggest coal miner, Peabody, is facing bankruptcy.

In Germany, the value of 46,000MW of coal plants will be written off to zero if the country gets serious about meeting the Paris targets, which demand a much tighter timeframe than even those contemplated by the Merkel government in its “energiewende” of energy transition.

The same is true of Australia, which is offering a meagre 26-28 per cent cut in emissions by 2030 – well below what any independent analyst is suggesting as the minimum required reduction – with no clear policy of how to get there.

The Climate Institute said this week that Australia’s last coal plant will need to be shuttered by 2035 at the latest, but coal generators such as AGL Energy insist they run for at least another decade.

The IEA report said global emissions of carbon dioxide from the energy sector stood at 32.1 billion tonnes in 2015, having remained essentially flat since 2013. It says renewables have played a critical role, having accounted for around 90 per cent of new electricity generation in 2015.

Wind, alone, produced more than half of new electricity generation. In parallel, the global economy continued to grow by more than 3 per cent, offering further evidence that the link between economic growth and emissions growth is weakening.

In China, coal generated less than 70 per cent of electricity, 10 percentage points less than in 2011. Over the same period, low-carbon sources jumped from 19 per cent to 28 per cent, with hydro and wind accounting for most of the increase.

Climate Council chief executive Amanda McKenzie said it is clear what Australia needs to do. “We need a plan to close our ageing and inefficient coal-fired power stations, which are some of the most polluting in the world, to make way for renewable energy.

“Without policies to facilitate this transition, Australians will not be protected from worsening extreme weather events and we will not be positioned to seize the economic opportunities of the global switch to clean energy.”

Bandt accused Turnbull of “waffling while the planet burns.”

“Malcolm Turnbull must live up to his past rhetoric on climate and ditch Tony Abbott’s weak and dangerous pollution targets and Direct Action policy. Malcolm Turnbull must commit to renewable energy and the end of coal.”