Things are moving quickly in Australian energy markets. Less than two years ago, the biggest utilities in Australia were still describing rooftop solar and distributed generation as a “non trivial” (their language) threat to their decades-old business models.

But my, how things change. The big network operators are talking openly of their consumers going off grid, and whole towns being served by local mini-grids. The big three “gentailers”, meanwhile, are rolling out new services – installing and owning rooftop solar systems and selling the output to consumers – in a bid to stay relevant in the energy game.

Now, the big gentailers – having spent much of the last two years arguing for renewable energy schemes to be cut completely or wound back significantly – are falling over themselves and each other to try to prove their green credentials.

Part of this is being driven by new offerings from competitors, and by campaigns to consumers to quit coal, as this image shows. It appears that the big utilities have been shocked by the response from consumers, even when they have sought to match cheaper and/or cleaner options elsewhere.

Part of this is being driven by new offerings from competitors, and by campaigns to consumers to quit coal, as this image shows. It appears that the big utilities have been shocked by the response from consumers, even when they have sought to match cheaper and/or cleaner options elsewhere.

The latest example came from AGL, whose change of emphasis since new CEO Andrew Vesey took over a month ago has been significant. AGL is seeking to play up its renewable energy investments at every opportunity, and last Friday, in his first public comments, at the completion of the 102MW Nyngan solar farm, Vesey announced that AGL was giving up coal.

Well, not really. AGL Energy did nothing more than commit to phasing out its current fleet of coal-fired generators – all bought in the last three years at a cost of some $6 billion, including debt – by their previously nominated dates.

That means burning brown coal at Loy Yang A – Australia’s biggest single emitter – for another 34 years, effectively doubling its life. And it allows AGL Energy to hedge its bets on whether it would close down Liddell, which it bought for basically nothing from the NSW government, by 2017, as it had once indicated, or by 2022 under its revised strategy. Neither really fits into the 2°C climate goal, but it at least it’s a change in rhetoric, and climate activists say it is a step in the right direction.

So, what would Australia energy retailers do if they were really serious about addressing climate change and showing leadership in clean energy?

Activists would say it should be a commitment to transforming the energy grid to a high percentage of renewable energy as soon as possible. The reality, though, is that changing economics and changing customer habits and demand is likely to have a bigger impact on their strategy than climate politics.

Despite getting big headlines in the mainstream media about its “exit from coal”, the real significance of what AGL is doing lies behind the scenes, or more importantly, behind the meter.

As RenewEconomy pointed out last week, AGL is investing heavily in a “new energy” division that Vesey has invited to challenge the incumbent business. It will be the big test-point for utilities – how they respond to the changing dynamics of energy use that could see half of energy demand being satisfied by the customers themselves – a long time before the scheduled closures of massive centralised power plants like Loy Yang A.

This concern is borne out by a recent analysis from Morgan Stanley, which sees the big threat to AGL coming from distributed generation, solar and battery storage, and how the company – and those like it – deal with that threat.

No wishful thinking from rusted-on greenies here, just some number crunchers wanting to know how it is that AGL thinks it can manage the dramatic revolution in the energy industry that has already forced Europe’s biggest utility to park its fossil fuel assets in another company, and the biggest generator in the US to declare that the era of centralised generation is about to end.

In the report, “AGL Energy, a Sense of Urgency,” Morgan Stanley analysts led by Rob Koh outline the key questions they want answered when Vesey announces the details of his “roadmap to the future,” in late May.

The big questions surround the cost of competing technologies, such as solar and storage, the structure of electricity tariffs, customer loyalty, and the threat that consumers may simply want to quit the grid.

This, Morgan Stanley notes, is a tricky position for retailers such as AGL, particularly given the push to increase fixed charges to compensate for declining demand from households and businesses.

This, Morgan Stanley notes, is a tricky position for retailers such as AGL, particularly given the push to increase fixed charges to compensate for declining demand from households and businesses.

“Put simply, we think AGL will have a hard time winning customers while explaining to them that their bills are going up, despite their energy usage going down,” Morgan Stanley writes.

“Perhaps the biggest potential source of customer dissatisfaction will be from households with solar panels.

“Part of the investment thesis for the solar householder is that household electricity bills will be lower after the installation. The householder savings results because kilowatt-hours generated on the rooftop reduces kilowatt-hours drawn from the grid, which reduces energy bills based on kilowatt-hours.

“However, most of these householders will not cut off completely from the grid, and therefore may face higher bills under tariffs based on kilowatt capacity. This problem will be particularly acute, in our view, for householders who have made investments without factoring in these potential changes.

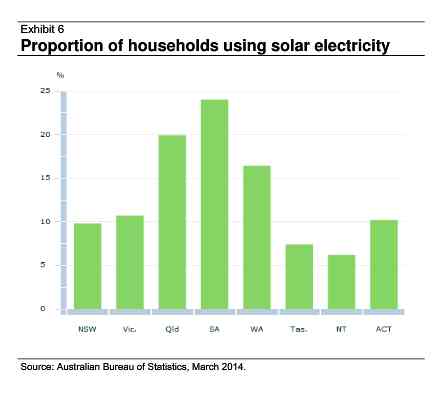

“Household solar is an incredibly popular product (see graph above), so these pricing reforms could potentially spill over into the political realm, in our view.”

Morgan Stanley says battery storage systems have the greatest disruptive potential to market conditions in Australia, and grid-scale deployment – which is already occurring – and/or widespread household deployment could conceivably replace the need for shoulder and peak generation.

This would further depress average pool prices, creating problems for the economics of the coal and gas fleet, and radically changing the investment requirements for grids.

AGL itself has said it is in early discussions with battery suppliers, but they have not yet conducted detailed research into customer willingness-to-pay or market sizing.

The consumer trends are critical. That’s because the consumer market for a company such as AGL is used to justify – and offset – its large generation fleet. The way the companies have been structured, one depends on the other. It is why companies such as E.ON have decided to split into two, because they can’t see how the two parts can co-exist when solar, storage, mini grids and electric vehicles represent such a deep threat to the centralised generation.

On that score, Morgan Stanley also wants to hear more than just repeats of the current “use-by” dates of the coal fleet. It wants to hear information about remediation costs, particularly in light of the massive over-capacity in baseload generation in the country. It concedes that AGL “should be one of the last exits, based on their low-cost positions in the merit orders.”

Most of all, it wants AGL management to be “agile and flexible” enough to respond to big and quick changes to the industry. “The pace of change is increasing,” Morgan Stanley says. “We therefore think that all utilities need to increase their capacity for agility and flexibility.”