Energy is a complex area, and it’s becoming even more complex. Traditionally we have separated thinking on electricity (mostly from coal) and gas, with a bit of petroleum for households and small-medium businesses, with coal added for big industry. Transport has been separate. That’s changing – fast.

Energy efficiency, with its multiple benefits both within and outside the traditional energy system, has mostly been Australia’s ‘forgotten fuel’.

For example, at the 2025 Energy Efficiency Council annual conference, energy minister Bowen acknowledged it was important, but described it as ‘embroidery’ of decarbonisation and transition to renewable energy.

One dictionary definition of embroidery is ‘something pleasing or desirable but unimportant’ ( EMBROIDERY Definition & Meaning – Merriam-Webster ).

In contrast to Australia, the International Energy Agency describes energy efficiency as ‘the first fuel’ and the European Union incorporates ‘efficiency first’ in its energy policies.

The design of energy markets has focused attention on energy supply and created tensions between profit and service to consumers, with consumers losing much of the time as outdated economic fundamentalism has dominated energy policy.

Even so-called ‘consumer centred’ policy is mostly ‘top-down’, trying to ‘empower’ consumers, as long as they are numerate, own their homes, have lots of time and who trust energy businesses and policy makers to treat them fairly.

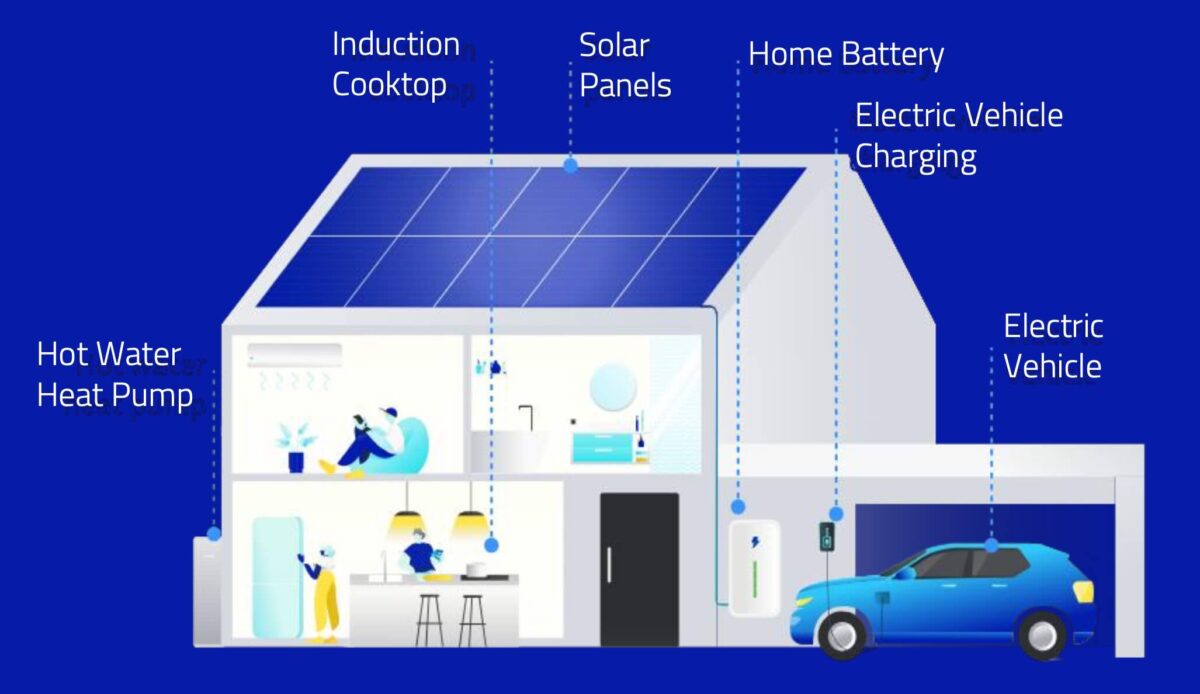

It relies heavily on ‘smart’ technologies and its emphasis is on shifting demand around, often by empowering energy businesses to ‘encourage’ appropriate consumer action and control their solar systems and batteries.

At the same time, despite the clamour about high energy prices, a recent Australian Energy Market Commission report (see graph below) suggests an average household spends about $2500 a year on electricity and gas – under $7 per day or about 3 percent of the ABS estimate of average household expenditure.

It’s not a big item for an average household. It’s not surprising that many households don’t focus much on this.

Energy policy makers that focus on pricing to drive change live in a world of bounded reality if they expect small impacts on consumer living and business costs to drive significant society-level behaviour change.

Of course, there are quite a few households and small businesses paying up to three times the average, and facing high energy bills on top of many other increasing costs.

Some high consumers, particularly renters, earn and spend less than the average. Some are too frightened to use energy for basic services, fearing they won’t be able to pay their energy bills.

Energy bills tend to come in big lumps, especially in winter when some voters face energy bills over a thousand dollars, so that does focus attention, but it’s often swamped by bigger issues and anger at energy suppliers and governments, not action.

In contrast to the small financial cost for average consumers, fossil fuels produce over 80 percent of Australia’s carbon emissions. Emissions from our fossil fuel exports are much bigger – but not our problem under international carbon accounting rules. Cutting energy-related emissions should be a high priority if you are concerned about climate change.

Electrification and efficiency

AEMC, like many other policy makers and advocates, attributes expected cost and carbon emission savings to electrification, but most of this should be attributed to energy efficiency.

Heat pumps are at least 300% more efficient than electric fan heaters and traditional resistive element electric hot water services, as well as being more efficient than gas appliances. And new 7-star homes require only a third as much heating and cooling thermal energy as many older homes. It is possible to ‘inefficiently electrify’.

Most energy businesses don’t make more money out of end user efficiency. Their efforts on consumer energy efficiency are driven by factors such as desire to reduce costly customer churn, manage reputation and, especially for gentailers, optimise overall portfolio profitability.

While the emission intensity of grid electricity is falling fast, it is still three times as emission intensive as gas per unit of purchased energy. It is only the high efficiency of key electric appliances and new buildings, and the poor efficiency of their gas alternatives that cuts emissions today.

OpenElectricity shows NEM emission intensity is tracking down below 0.6 kg CO2e/kWh towards 0.5 – that’s 0.14 kg CO2e/megajoule generated. Fossil gas emission intensity is 0.053 kg CO2e/MJ – over 60 percent lower.

If electric efficiency is 300% higher than the gas appliance efficiency at the recent 0.6 kg CO2e/kWh, electricity emission intensity matches fossil gas emission intensity per unit of energy purchased.

Increasing large scale renewable electricity generation and energy storage is driving grid electricity emission intensity down. For example, Victoria has halved electricity emission intensity over the past 15 years or so, and is forecast to halve it again to around 0.3 kg CO2e/kWh by around 2030.

Increasing use of behind-the-meter renewables and batteries is already allowing individual electricity consumers to achieve big reductions in electricity emission intensity.

Over the life of an efficient new appliance, industrial equipment or building, lifetime emissions from grid electricity will benefit from ongoing reduction in emission intensity of electricity, and deliver increasing climate benefits relative to fossil gas.

When electricity emission intensity reaches 0.2 kg CO2e/kWh, it will match the emission intensity of fossil gas per unit of purchased energy. Much higher electricity efficiency will mean actual emissions from delivery of services by electricity will be much lower than gas use.

Demand management – when we use energy, is also important. Stresses on supply systems vary in real time and seasonally in both cold and hot weather. Winter problems include long duration high demand and low solar. Electricity markets now place changing value on supply and services from seconds to seasons.

Lower utilisation of expensive electricity supply infrastructure, if we have high peaks in demand, increases fixed electricity charges.

High demand peaks are driven by inefficient buildings, appliances and equipment and physics – consumers are just trying to stay comfortable or run their businesses. Peak demand is amplified by the reality that heat pump efficiency is lower when temperatures are extreme.

Of course, overall emission intensity is more complex. Methane leakage from both gas production and supply and coal mining, and use of 100 year averaged emission factors distort perceptions