Australia has 10 million households, and these households are likely buy 100 million machines over the next two decades – cars, heaters, and cookers. If the country is to have any chance of reaching zero emissions by 2040, the new reality for a 1.5°C climate target, then all those new machines need to be electric.

Australia has 10 million households, and these households are likely buy 100 million machines over the next two decades – cars, heaters, and cookers. If the country is to have any chance of reaching zero emissions by 2040, the new reality for a 1.5°C climate target, then all those new machines need to be electric.

That is the clear message from Rewiring Australia chief scientist and electrification evangelist Saul Griffith, and pretty much everyone else speaking at the Smart Energy conference in Sydney last week.

There is so much focus on big wind, solar and storage projects, and major transmission projects, that the household and the decisions made there often get overlooked.

And yet, Griffith points out, 42 per cent of Australia’s emissions come from the decisions made around the dining table, and another 29 per cent of the country’s emissions come from small businesses whose owners likely eat at that same table.

This is now becoming critical. The delays in Australia’s and the world’s efforts on emissions reduction means valuable time has been lost. Scientists make it clear that “net zero” by 2050 is not good enough for a 1.5°C target, it needs to be “absolute zero”, by 2040. And that won’t happen without the support of households.

“We have got to go really fast now, faster than you think,” Griffith told the conference. “It really just has to be by electrifying everything right now.

“We’ve got 10 million households that are going to buy 100 million machines in next two decades, And those 100 million decisions need to be easy, they need to be economically good for the household, and we need to have all the policies and everything aligned.”

That, Griffith and others told the conference, is going to require a bunch of different things.

One is to diminish the power of the fossil fuel lobby in Australia. Greens leader Adam Bandt told the conference that Australia is already looking like a “petrol state” and has one last chance before blowing its opportunity.

Griffith pointed out that the fossil fuel industry is so entrenched it now costs more than $1,000 to disconnect gas from the home.

“The gas industry has captured Australian energy policy,” Griffith said. “We’re gonna give the gas industry $10 billion as we try to get them out of their homes.”

The second important thing is to switch the focus to going electric, rather than just being efficient – a noble and obvious goal that never really caught on in the way it should have.

Here’s why. The top graph shows the efficiency gains that have occurred, compared to the gains that could occur with full electrification, which eliminates all the wasted energy inherent in fossil fuels.

The Australian household should be at the heart of that transition to electric. In just about everything people do, energy is wasted – via generation losses, vehicle fuels, cooking and water and space heating.

Energy use will go down by 64 per cent just by electrifying everything – even though individual household electricity consumption will rise nearly three fold.

“By electrifying your car, you use less than 1/3 of the energy to power that car. It’s the same with water heaters. Being gas efficient gave us tiny wins, but we need to electrify,” Griffith says.

Hence the need to focus on distributed energy in the national grid and the role of households – something that rule makers and regulators have talked about, but not really acted on with anything like the urgency required.

This is particularly important in the ongoing and deepening debate about the need for transmission links and optimising the distributed energy resources. Policy makers and regulators are being urged to get the balance right.

“We are underestimating how much of our electricity we can actually generate on our rooftops and within our communities,” Griffith says.

“If we had the incentives set more sanely in the rules of the NEM (the National Electricity Market), and we were prioritsing households and communities, we could be selling that rooftop solar to each other much more cheaply.

“And we could be exploiting community assets, whether they’re transport corridors, whether they’re car parks, whether they’re commercial buildings, city buildings, public housing, etc, … and selling that community electricity each other.”

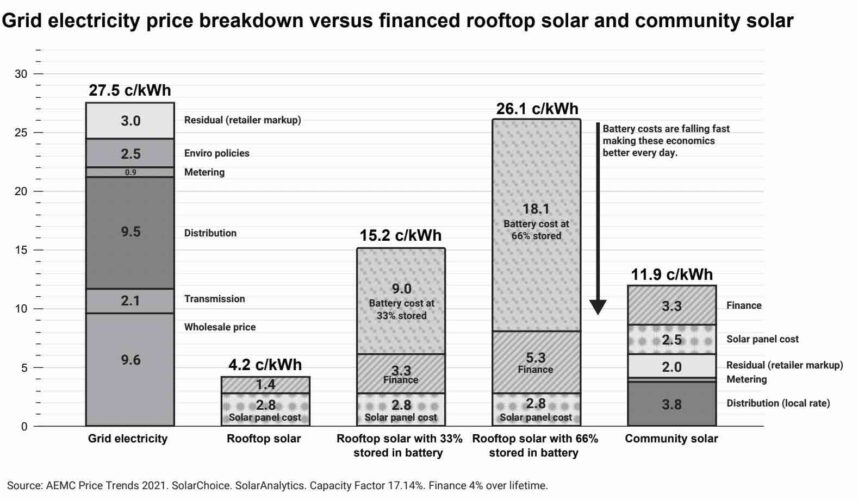

Griffith used this graph above to highlight the difference between the cost of big, centralised power delivered through big networks, and the costs of distributed energy to the household.

He says policy design needs to focus more on encouraging these distributed assets, rather than trying to bury them in the grid. And he notes that for all the reforms of the NEM over the last couple of decades, prices have gone up rather than down. “This is a giant regulatory hurdle to enable the future,” he says.

How can this electrification be achieved?

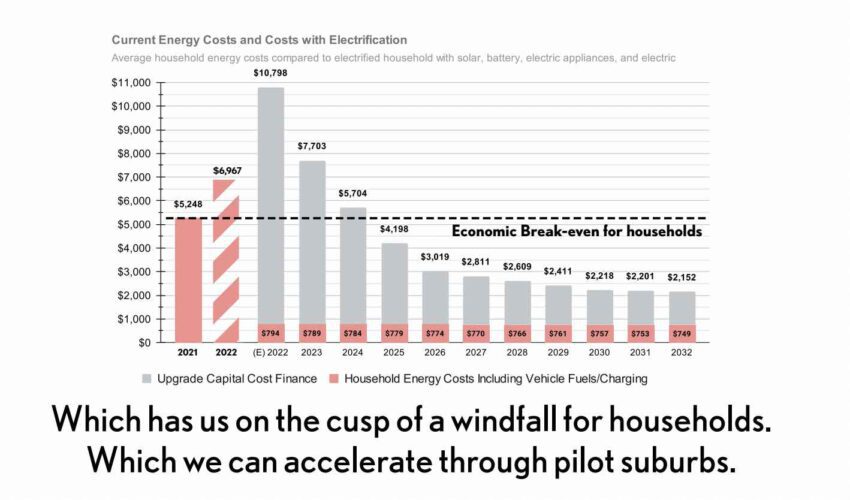

Financing will be critical. And policy support. The economics are already favourable, as the graph below illustrates. Australian households pay up to $7,000 a year on energy costs (including cars), and going electric will deliver significant savings over the life of the new machines.

Capital costs for battery storage and EVs are falling. But not everyone has the capital to make that initial investment .

“If I could finance some Australian household today to electrify both vehicles… put solar on the roof, electrify the kitchen, the heating, etc, they’d have an ongoing cost because they’ve converted future fuel costs to the fixed cost of finance of about $2,000 a year for all of their energy needs.

“That price will get cheaper every year because the cost of solar and batteries as we heard today is going down. So this is now a great deal for the country.”

That’s why federal and state budgets are important, because they can play a significant role in encouraging people to choose electric the next time they do a renovation, or replace the cooker, heater or car. There are 17 budgets to go before 2040 – 16 after the new budget to be delivered on Tuesday.

Communities can also work together. In Griffith’s own postcode, 2515, located south of Sydney, he estimates that around $20 million is spent each year. Three quarters of that comes from fossil fuels (cars and gas in the home), and one quarter of it on grid power.

“Most of that money is being spent at the one petrol station in the community, where they also sell you nicotine and sugar – three things that can kill you in one place,” Griffith says.

“Fast forward to the future if we we can easily generate at least two thirds and potentially all of our electricity if we fully utilize our rooftop and community assets. We would still be buying some electricity from the grid.

“We’d be creating a million and a half dollars a year in local electrification to labor about 25 jobs. We’d be saving about $21 million a year.

“The real point is if we are not spending that money at the petrol station, we’re now spending money that money and investing in our communities, This is how we create an unbelievable number of local, real jobs everywhere in the country.”

The final part of the equation is to make this simple. Griffith is in do doubt about the economics of going electric, but households need to understand this – not easy when the gas industry is spreading nonsense and fear campaigns about the future of the Aussie BBQ.

And as Jon Jutsen, the head of RACE for 2030 (RACE stands for Reliable Affordable Clean Energy) points out, implementing these transition is not easy.

Jutsen has just gone through the process of electrifying his home, and despite his years as a leading advocate of energy efficiency and being an expert in the field, he found it difficult and confusing.

“No one knows how to integrate this stuff. There’s no control systems that are available to optimally control and integrate live systems with the grid … it’s really a quite challenging exercise.”