Modelling for Australia’s transition to a near 100 per cent renewables grid shows high levels of curtailment in the future, particularly for large scale solar farms.

But it may not be as bad a problem as it’s imagined to be. It might turn out to be the most efficient outcome, because oversizing the solar capacity will mean less storage is required (and some of the excess may be mopped up by green hydrogen electrolysers in any case.

The draft version of the 2022 Integrated System Plan released on Friday by the Australian Energy Market Operator assumes that by the early 2040s coal generation has ceased and the grid is running on wind and solar for nearly all its supply, backed up by storage and some remaining fast start gas generators.

AEMO says its modelling shows that rather than build network and storage to capture every last watt of energy, it is sometimes more efficient to curtail or ‘waste’ some generation.

“This may occur when there are system security or other operability constraints in the network, or there is simply over-abundant renewable energy available,” it writes.

It says that there will be times when there is simply not enough operational demand to utilise all available renewable resources.

“Adding more storage to soak up the surplus supply is unlikely to be economically efficient because, with so much annual renewable generation, there is little marginal value in shifting VRE to other times in the day, month or year,” AEMO says.

Most of the curtailment will happen in the daylight hours, because of the role of rooftop solar, which is tipped to grow four fold over coming decades. And it also happens mostly in spring and summer when rooftop solar produces more.

“This indicates that, based on future technology cost estimates, installing sufficient VRE to meet the energy needs of winter and accepting some curtailment in summer is likely to be a more efficient outcome than the alternative of building less utility-scale solar but more seasonal storage,” AEMO says.

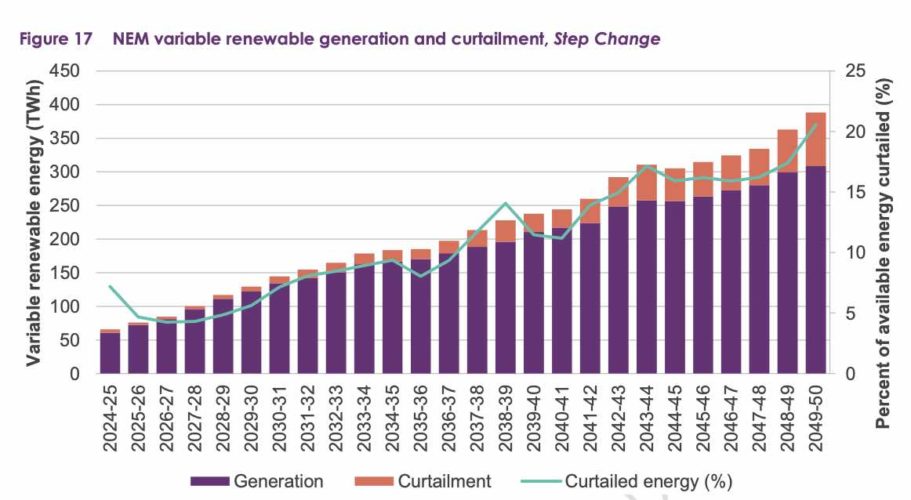

As this graph shows, by 2050 the amount of curtailment of solar power could be 20 per cent, or even higher, by 2050, up from current levels of around four per cent.

That may be of little comfort to the developers of solar farms who might be wondering about their ability to generate revenue. But the chances are that the scenarios will change in any case.

In the last ISP in 2020, the “step change” scenario was considered to be an outlier, now it is the central scenario in the new draft ISP for 2022.

The new “stretch” scenario is “hydrogen superpower”, which envisages even more wind and solar – up to 350MW of solar by 2050, mostly to satisfy the huge demand from hydrogen electrolysers supplying industry and transport.

That is the only scenario that confirms with the 1.5° Paris climate goal, and is certainly a scenario that is being assumed by the likes of Andrew Forrest, who are talking of investing billions in renewable hydrogen facilities.

If they go ahead at the scale that Forrest is talking about, it will likely mean that any excess solar is more likely to be mopped up by electrolyser demand than being curtailed.

And, in any case, if the Australian government is right, solar costs would have fallen to a mere $15/MWh by 2035 – some analysts say it will happen a lot sooner, and fall even further over time. And at those prices, who cares?