As an analyst, themes generally tend to emerge and hold court for a while. A few years ago it might be grid forming inverters, two years ago it was wind costs. This year, one of the ITK themes is the role of DER, or distributed energy resources.

This note is not even a drive off the tee to a long par 5, it’s a practice shot. The only conclusion I draw is that it’s not obvious to me that a new DER model will produce greater benefits than the current largely laissez faire approach.

The initial findings are:

– Australia is a leader, but not by much, in rooftop generation relative to the size of the market.

– Integration of rooftop solar into the total market is basically poor. There are basically two lobby groups, those who think that rooftop solar needs to just be a component of the integrated utility based market and those who think that distributed energy should be the foundational block around which utility scale generation fits. Despite the unplanned and – from the point of view of the NEM market – unmanned impact of rooftop solar, it’s arguably producing results that I approve of. That is contributing to forcing coal generation out of the mix, providing the juice for utility batteries to cut peak prices and giving consumers a degree of countervailing power to large Gentailers. It’s not definitive to me that we need to change much.

– At the moment and in general rooftop solar production is far in excess of consumption by the solar owners in the middle of the day. That is, there is a large excess of rooftop solar that is exported to the grid. This forces down midday prices, driving them negative in some areas in Spring; leads to curtailment of some utility generation and causes AEMO minimum demand anxiety, although I personally think that problem will decline as batteries’ buffer role grows. It also provides cheap or very free charging energy to utility batteries; results in falling feed-in tariffs, which creates its own market pressure.

– More generally, and as reflected in AEMO consumption forecasts, behind the meter solar volumes and growth means that that there is little or no growth in underlying volumes through wires and poles networks and little or no growth in retail volumes to households. It also means household electrification is required for utility supply to households to stand still, but the primary household electrification will take place in cars and then vehicle to the grid – or more specifically, vehicle-to-the-house – and this will further reduce grid capacity utilisation.

Solar production can still force coal generation out

Right now, rooftop solar forces prices down in the middle of the day, to the point where it’s hard for most to understand why anyone develops utility solar, but they do.

Coal generation at the moment can’t, in general, turn off in the middle of the day, despite some experiments that suggests it might be able to. So coal generation runs at a loss during the middle of the day.

Coal generators make their money back in the evening and morning peak and in the overnight market. Once utility batteries, particularly of longer duration, are introduced coal generators will become more uneconomic. For various reasons there may be less negative price intervals, but ongoing increases in rooftop solar will tend to keep midday prices very low.

The 20-30 gigawatt-hours (GWh) of batteries that will be operating by the time the next Eraring closure date becomes relevant will add to midday demand materially, but the batteries will tend to discharge into the evening peak. So coal generators will continue to lose money at lunch time but will have less peak revenue and, overall, all returns on capital will fall.

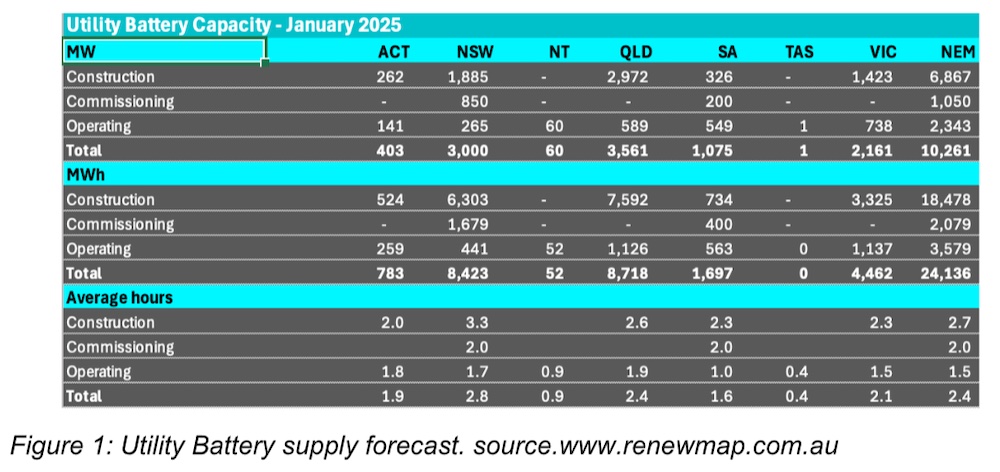

Bear in mind that by the time Eraring and Yallourn close utility battery capacity will have grown more than 5X over last year’s levels. To Renewmap’s excellent summary as at the end of January we can already add 1.4 GW of “close to FID” new announcements from the AGL interim result. And that surely wont be the end.

So we can already see over 11 GW and probably close to 12 GW and something like 27 GWh of capacity. It is important to note that not all of this will be available to be traded in the energy market. But the more that is built, the greater the share used in the traded energy market.

Let’s use New South Wales as an example – and the following simple analysis ignores home batteries, EVs and changes in transmission flows. These simplifications are in aid of making a general point. More specific forecasts can be obtained from ITK’s formal half-hourly price forecasting tool, or they could be if we released it more generally.

Rather than showing our guess of the answer, the following table shows some price forecasting inputs. Specifically, we assume battery output grows about 20X for each half hour relative to what was produced in the corresponding half hour last year. That still sees only half the estimated NSW battery power being used in any half hour. We also allow for 3% demand growth but subtract the estimated output from Uungula wind farm.

For the middle of the day our estimates show that the battery charging demand can largely be supplied by the growth in rooftop PV and if we allowed for more utility solar growth and 2 GW is under construction then I expect there is a net decline in middle-of-the-day coal generation.

The inference to be drawn is that batteries are going to really pressure Snowy and gas producers in NSW, particularly in the 5:30pm to 7pm window right when prices peak. As well as less Snowy output and less gas, I also expect a small amount of coal will have to make way. These numbers continue to suggest that prior to Eraring closing there will be strong pressure on evening peak prices.

Therefore, I conclude:

– The economic outlook for Eraring is poor and management will want to close the plant;

– Rooftop solar under the current laissez faire policy approach will work to lower prices and carbon output for all consumers by providing the energy for utility batteries to compete in the peak.

That said, once Eraring closes prices will likely rise again until more solar, batteries and wind put pressure on the next coal generator.

Do we want households to be self sufficient or to export?

It intuitively seems that producing electricity close to where it is consumed will be cheaper. But that is far from a universal truth. The whole point about large coal generators is that their cost was so low relative to small generators that it made sense to build transmission. The history of the NEM is it grew out of local councils closing down local uneconomic generators and building a state-based and then NEM-based system.

But now things may be changing back the other way.

I personally don’t think there is a definitive study that compares the cost of a system with lots of household batteries and less utility batteries with the cost of a system that emphasises utility batteries mostly charged from exported rooftop solar.

The ISP did have a lot of household storage in the 2022 version and less in 2024, but the economics weren’t discussed to any extent because the household storage isn’t modelled economically from a system point of view but only from the household point of view, and then by a consultant.

Even before considering distribution, transmission and maintenance costs there are also issues of market power and competitiveness that are not easily modelled. Mass production in a factory and learning rates can sometimes result in costs being lower despite size economies of scale. And all other things being equal a system with more power is better than a system with less power.

In general, residential batteries installed in Australia are more expensive than utility batteries and EV batteries are cheaper again, but there is clearly scope, in my opinion, and examples of residential batteries selling under utility battery prices.

As a very broad generalisation, and using Tesla Powerwalls, the earlier version as the benchmark, then household batteries have about 2.3 hours duration if discharged at the maximum inverter rating. I have long believed that the grid in total will be more resilient if the energy and the power requirements are distributed and individual or small units are capable of being islanded.

Trials and models

Australia is well known for having a thin transmission network. In Victoria, single wire earth return (SWER) transmission is associated with bush fires. In WA costs of maintaining transmission have lead to the development of islanding models, that is most of the electricity is supplied by solar and battery with backup diesel generation.

In general, I maintain a view that solar and batteries distributed round the grid, batteries in every street, street level islandable grids is both technically feasible and possibly in the community interest.

There are now more and more examples of stand alone grids and the economics look better and better as transmission costs rise but solar and battery costs fall. Norfolk Island, for instance, or Yackandandah. These are geographic-based microgrids but there are also NEM-wide market based trials.

Australia is in leading bunch in rooftop generation share

To provide some context I used the IEA data to obtain the top 10 countries for cumulative total installed behind the meter capacity, as at the end of 2023. I then used Claude to get some other data which I audited (sample checked) for reasonableness.

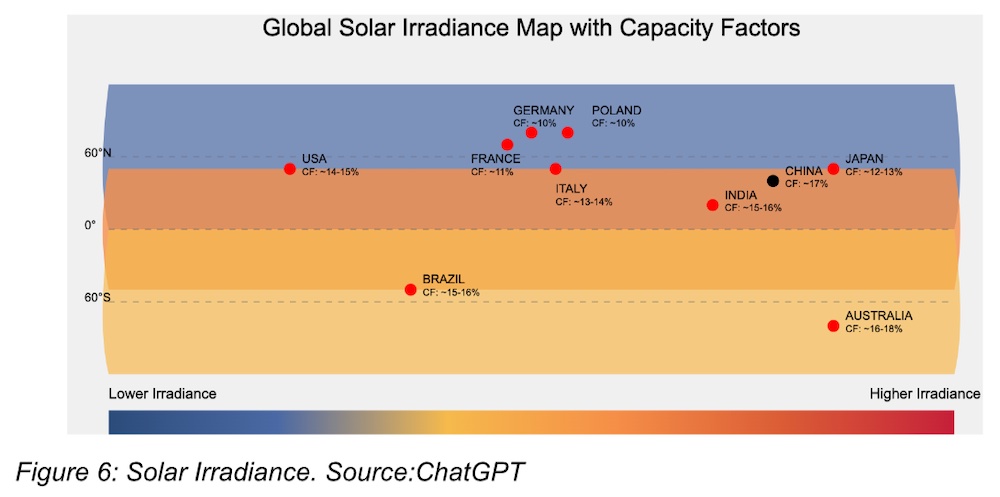

Australia is the largest of the top 10 when the metric is rooftop solar output as a share of generation. Amazingly it’s only just ahead of Germany. Actually I think Claude’s estimates of rooftop capacity factors by country is a little bit on the high side.

Capacity factors are mostly based on this Claude-created irradiance map but cross checked against other sources.

What stands out is what a good job Poland has done and, equally, what a crap outcome in India. How India can ever expect to get ahead when it doesn’t take advantage of its natural advantages is a mystery to me. One of many mysteries, it must be said.

Overall, though, the message is that Australia is a global leader in behind-the-meter solar as measured by the total energy output compared to total demand. But Germany is only a whisker behind and then only because its irradiance is so much worse.

Rooftop PV meets up to 35% of grid demand in Summer

The following figure uses Queensland and it’s pretty much peak solar, but even so it’s clear what a big force rooftop is.

And what we see from the wholesale market is the familiar sight of prices being forced down in the middle of the day towards zero and then everyone making money at dinner time once solar has gone.

And this, of course, provides a huge incentive for utility-scale batteries and explains why so many of them are being built. A two-hour duration battery in Queensland, operated with perfect foresight, could have made a spread (sell price – buy price) of over $500/MWh in the past year.

Obviously, as more batteries are built spreads will come down, but the expectation at the moment is that rooftop supply will at least make the charging cost cheap into the indefinite future. And every time a coal generation unit closes another 400-600 MW of batteries are required at dinner time. In NSW the closure of Eraring means that over 2000 MW of new battery capacity will be required even for an average dinner time.

If consumers are to benefit from these utility batteries, because the supply of them encourages price competition, then keeping the charging cost low by continuing to create a surplus of power in the middle of the day may work out well.

The alternative is that policy restricts exports via network tariffs and low feed-in tariffs and perhaps policy that encourages household, community and network batteries. Which direction is better?

Consumer point of view

The economics of rooftop solar remain relatively attractive in Australia. The outcome depends on the self consumption rate, that is the proportion of the rooftop system that is not exported back to the grid but consumed in the house.

For a pure solar system, that is no battery, the IRR (internal rate of return) is around 16% using even reasonable assumptions for a family house. That is a six-year payback. The more you consume behind the meter the greater the IRR. Note that the following figure uses just $20 for the feed-in tariff, and I have used a flat tariff for grid supplied electricity.

In NSW, according to Solar Choice’s long running and highly regarded solar cost index, the average installed cost of solar is $A0.89/watt which does include the subsidy benefit. So-called high quality systems have an average installed cost of $1.1/watt.

The solar system on its own is inflexible, as a consumer your only way to add value is to switch consumption to behind the meter. So for instance charging your electric car at home. Or running the air con during the solar hours effectively storing the cool air for an hour or two at dinner.

Nevertheless the fact that solar panels are a good investment and that they fix a significant portion of electricity prices from the consumer’s point of view into the long term future, means that they keep getting installed at the same rate as always.

The solar consumer’s point of view is kind of selfish. Effectively it pushes more of the grid cost onto non-solar households. The invested capital in the grid has to be paid for and it has to be maintained. Equally, though, as home solar and battery penetration increases the grid “capacity utilisation” will fall.

It’s also worth noting that the installed price of panels in Australia in terms of $/w is about one-third that of the USA. Let’s not talk about the reasons, but in this regard we are the lucky country.

Household batteries – lower price systems enter the market. Here we go

The great hope is that household batteries will show the same kind of price reduction as solar panels, or EV batteries, or even utility-scale stationary batteries have done. But in the 15 years or so I have been tracking things the price has barely changed. Functionality has certainly improved, but the cost not so much.

By comparison, car battery pack prices have halved between 2017 and 2024 and are about 1/6 the price of a household battery in Australia.

I understand the AC/DC conversion, the installation costs and so on but they don’t justify paying 6x as much, or at least I need to have the difference explained to me in much more detail.

Some might argue that the window for household batteries may not stay open for much longer because EV to the grid is going to do most of the work. That may be, but a better concept is still just around the corner whereas price is pretty much the only drawback for household batteries.

It’s worth mentioning that as well as price the residential electrical system needs to be up to scratch. For instance in my network area Ausgrid looks at your maximum export capacity as the sum of the solar output + the maximum battery AC power and so 3 phase power might be required. On the other hand once done your EV charger can run at 11 KW.

Ah the point here is that household batteries are not yet seen as sufficiently attractive to get the installation rates we have long waited for. What is needed is more determined competition. Supply capacity and inventory needs to be built up possibly via government incentives or possibly by, say, a Chinese battery manufacturer having a real go.

Right now my impression is that Tesla Powerwall is the market leading product and its price point is the industry price point. Tesla’s position comes from being first and probably because its software has historically been good.

Here comes the cavalry

That said, there are residential batteries that are much cheaper than the Powerwall on the market. For instance, the ESY Sunhome has an RRP of $4,900 for a 10 KWh model pre installation which works out to 1/2 the installed price of a Powerwall at around $A500/KWh. The battery receives a decent review and has a good guarantee if you assume the manufacturer will be around.

At the ESY price battery economics are comparable to those for solar and I expect if the ESY price was the industry price household battery sales would grow strongly.

The ESY battery is warranted for 60% of its capacity after 10 years. In the following table I have made some optimistic and some conservative assumptions.

– Assumed a full 10 KWh of capacity for 10 years and then replaced the battery modules, only over a 25 year life the batteries are replaced twice. In all likelihood the inverter would need to be replaced as well..

– Ignored the round trip efficiency calculation in this very rough demo.

– Assumed only a flat avoided price of $0.32/kwh when anyone sensible doing this would go on a time of use tariff and the avoided cost is more like $0.52/kwh.

– Assumed underlying household consumption of 8 MWh per year which believe me is not a lot for a family house.

Otherwise the feed-in tariff taken as the charging cost (what you could have earned instead of charging the battery) and the percentage of consumption behind the meter are taken from the solar example. At a capital cost of $600, basically everyone with solar panels should be adding a battery.

An IRR of 17% is more than you will get in the bond or share market. NB: I am not doing this to promote ESY – a product about which I know nothing. It’s done to show that households should fall over themselves to add batteries at that price. Even a 10-year life but using peak hour prices of $0.50/KWh produces a great return.

In my view it would only take a small amount of policy to create a market where households would add batteries. Even an advertising campaign and a small subsidy would likely be enough to send the signal to consumers that we all think this is a good money making idea.

Most households still do not have a time-of-use meter.

Under former AEMC boss John Pierce’s Power of Choice model time-of-use meters were something customers had to ask for. The benefits to the system could be ignored. As a result, outside of Victoria it remains the case that most meters are not time-of-use.

However, more recently, in a final rule published in November ’24, the AEMC has mandated retailers to accelerate the deployment of smart meters, with the program to be completed by 2030. This, to me, is clearly a good thing. But consumers’ number one thing appears to be simple low cost. Electricity remains a grudge purchase. Smart meters wont make things simpler.

Retail tariffs and market structure

It’s at this point in the discussion that I ask myself if deregulation has worked as intended. In my view:

– The market remains dominated by large gentailers. I doubt there has been much significant change in market share of the big three or four retailers in recent years. Nor is it clear that any second tier retailer has a dominant strategy. In general going with a second tier retailer carries some extra risk for households. Equally second tier retailer have to buy energy often from competing gentailers . Hedging costs are higher on a unit cost basis for smaller retailers and after customer numbers reach a certain point you basically need to win two customers to get a net gain of one.

– At the same time there is unlikely to be any volume growth in the household sector from the point of view of the gentailer. That’s because market share is cannibalised by rooftop solar and now batteries. This increase in self sufficiency offsets the boost to gross consumption that comes through household electrification and household vehicles electrification.

– Gentailers aim to make retail tariffs as simple as possible. From this point of view networks are nuisance.

– At the moment big Gentailers have no incentive to promote time of use or demand tariffs. It is very clear that big Gentailers try to make things as simple as possible. Essentially a customer looking for a quote will be shown three variations of the one plan either fixed tariff or time of use. The customer will not be shown both a time of use and fixed tariff plan. For a customer that was previously on a fixed rate plan seeking to change retailer, each of AGL, ORG and EA will show three fixed rate plans. All of the plans will have similar prices but one will be cheaper and I expect most customers will choose the cheapest one. As far as I can tell the plans and prices quoted by all three Gentailers will be similar to each other.

– My point here is that for the big gentailers the successful strategy that preserves market share and minimises churn and costs is to keep it as simple as possible. Don’t confuse the customer with real decisions, don’t really compete on price too much. To the maximum extent possible ignore whatever policy and incentive networks are pushing this year. Really it’s like competing on paint colour in the car business. There are three shades of grey. It’s true that big gentailers do have some innovative products like VPPs, but they are a small segment. Equally small retailers have lots of different plans and have ended up with about 25% of the market.

The result is that the market is now fairly stable with very gradual erosion of market share by the majors. The following figure is recreated from an AER chart and some numbers may be out by the odd percent. Over the past five years tier 2 retailers have picked up maybe 4% market share in aggregate. Origin and AGL are clear leaders and Energy Australia a distant third.

Online quotes – the process is a joke from the point of view of changing behaviour

As far as I can tell, when you get an online quote from one of the big gentailers the first thing that happens is that the retailer goes away and looks at the meter to determine whether the existing plan for the “house” is on a flat rate or a time-of-use tariff.

If the house is on flat rate, as most are, then you will only be shown flat rates. If you are on a time-of-use plan then you will be shown time-of-use plans. Again, as far as I can tell, in the Ausgrid NSW franchise you will be shown a cost based on either 6.8 MWh per year or 3.9 MWh per year.

Simply put, if you are on a flat rate tariff and you look for a better deal, and speaking only for the big 3 gentailers, then when you get a quote you would not know it was possible to go on a time-of-use tariff. To get on one you would have to speak to the call centre (or its Bot.)

And the reverse is true, if you are on a time-of-use tariff you would not be shown a flat rate tariff.

As we discuss below, customers on fixed rate tariffs are likely to end up on network demand tariffs. They won’t understand those tariffs and won’t understand that they have to pay for the rest of the year for putting the aircon on at Christmas dinner. In theory, if they did understand they might choose to go on a time-of-use tariff. But as things presently stand their retailer won’t offer them the choice to go on time of use. The gentailer will offer two nearly identical flavours of flat rate.

And in the gentailers’ defence, if the customers were offered a time-of-use tariff they would likely see it as the gentailer trying to exploit them.

The role of the distributor

I always get grumpy when I talk about distributors because they make policy decisions that cannot be influenced by customers, only by the regulator. A bunch of network experts sit around and decide on 40-50% of a customer’s electricity bill but never have to face the market.

In the case of Ausgrid, it wants existing flat rate customers to move to demand tariffs. Residential customers have little or no ability to manage demand. A determined customer can run the dishwasher at lunchtime I guess, if the dishwasher has a timer and or some one is home in the day, but asking a busy family to understand whether their electricity consumption is high or low is just a joke.

The AEMC has determined that retailers can’t put customers onto demand tariffs without their informed consent. In the unlikely event I read the AEMC paper properly this informed consent can be ignored once a new meter has been in for two years.

I’m not sure how this will play out. I think the chance of getting the broad mass of clients to sign up to demand tariffs is not very high but equally, over time, those who don’t move to time of use will likely end up on demand tariffs whether they sign up or not.

Rob Passey showed long ago that individual residential maximum demand is not coincident with maximum demand in the network. On top of that, the networks at the moment mostly have reasonable substation capacity.

The likelihood is that the overall utilisation of the distribution network is likely to fall rather than rise, although wires and poles for new housing will be required. If household batteries and or vehicle-to-the-grid becomes a thing many households will essentially only be using the grid as a last resort. I guess with a demand tariff it’s that last resort that will drive the cost to the consumer. Still, it is likely that peak demand on the grid will rise.

That is the paradox of the wires and poles network. As batteries proliferate through the wires and poles network, consumers tend to become more and more self sufficient, neither exporting nor importing much but in general their average demand for network services falls. Yet from time to time, having electrified the the house, or because the batteries are full, they will either briefly be importing lots of power or potentially exporting lots.

In this way a customer could run their house grid-free for 364 days in a year and still end up with a big wires and poles bill because at Christmas it was raining and the family had all the relatives over. The household is unlikely to understand their family dinner resulted in a big annual electricity bill. A Christmas present to Ausgrid shareholders, so to speak. Hmm, maybe I am overdoing this.

Ausgrid is also going to force all solar customers (export capable customers) to go on “Export Tariff”. On this tariff if you export solar at a certain time of day you have to PAY an export price (plus – and it’s no fault of the distributor – your feed-in tariff will likely be next to nothing) and equally if you export power in the system demand peak Ausgrid will pay you a bit. At the moment cost and benefit are very small but they may not remain so.

Again, I make my usual points. (1) Ausgrid bases its tariffs on theory, it has no customers so it just does what it thinks is a good idea. (2) Retailers don’t have to, but I think generally do, set residential tariffs that simply follow network tariffs. (3) The retailer will incur a cost switching a customer from one tariff plan (flat rate) to another (time of use) and vice versa. The cost is the cost of contacting the distributor and getting the network plan switched.