The integration of CER seems to come down to three key things: (i) everyone having a modern meter, (ii) working out who loses when there is too much solar and minimising that loss through storage and (iii) working out whether we really want lots of household storage including EV related storage.

And if we do want those things, how is the network to be equitably funded?

What’s also clear to me is that for so long as networks are regulated monopolies, they can be safely ignored by everyone except the Australian Energy Regulator. They have so far been ignored despite the potential of networks to facilitate the transition and despite being the largest part of the electricity value chain.

Retailers do in fact ignore network tariffs, the ENA – the main lobby group – comes up with plans that don’t seem convincingly factually based and are naturally self serving, and in general we don’t know what customers want from networks because customers aren’t exposed to them other than for a blackout.

The one thing we can be massively thankful for is that in Australia, networks make it easy for households to have rooftop solar. That one thing is what has enabled our world leading rooftop position. It makes up for everything else.

And although I have toyed with preferring vertically integrated, geographic franchises like say the US has with Florida Light and Power, the experience with embedded networks here and the power to block stuff they don’t like, eg rooftop solar in the US, is actually supportive of the separation of gentailers from wires and poles despite the system’s obvious shortcomings.

The rest of this long rambling note tries to justify the assertions made above.

Is integration of CER really no more than asking where batteries should be located?

We are still at the beginning of a battery roll out in the NEM (National Electricity Market). It’s still very timely to ask what if anything should be incentivised. At the moment both household and utility and network level storage are all being encouraged to a greater or lesser extent. And now EV storage is coming.

The Integrated System Plan capacity expansion model ends up picking lots of household storage. Storage closer to load needs less transmission. Equally, though, storage close to utility scale generation can deal with variable renewables (VRE) transmission constraints.

Storage has the capability to double the capacity of double circuit lines. Imagine double the capacity of Humelink of VNI West, of Project Energy Connect just by using batteries and without building 1 more km of transmission.

Every household with a battery and solar will essentially just be using the grid as the last resort. If there are enough such households, ie if every property with solar had a battery, the wires and poles network revenue model would collapse.

At the moment there is no viable network revenue model for such a system. Whatever model is chosen it will penalise those households that don’t have solar/battery. It’s the same problem as solar itself causes but just a lot bigger.

On the other hand, if enough houses had batteries there would be next to need for new network investment except for population growth. You wouldn’t even need modern meters because they’d have nothing much to measure.

The pressure that rooftop solar puts on spot prices would go away, but whether that’s a “good” thing is another matter. Negative lunch time prices are great for storage operators.

Networks are big, but useless

Electricity distribution networks with over $60 billion of assets are just about the most valuable part of the Electricity industry. Investors love them and don’t have to worry about very much, a fixed return on capital (relative to inflation and interest rates) is locked in to eternity.

Yes, rooftop solar is a nuisance because it slows down the investment that grows the asset base but otherwise it has little impact. No volume, no problem, just put up the price to maintain revenue. Regulators prefer the revenue cap because now the networks are happy for more rooftop solar and that is indeed the preferable outcome.

What is for sure is that the Energy Networks Association continue to make claims of dubious merit. They say that connecting to distribution networks is cheaper than connecting to transmission but in fact under the present rules it seems it’s not.

How to change the rules is difficult particularly as the rules around transmission pricing are also changing. What is clear is that there is spare capacity on the distribution networks, but that mostly is only of interest to utility solar and that’s not a high return space just now.

The ENA claim that household batteries need subsidies when in fact network and community batteries get equal or bigger subsidies. Further network batteries appear to be 20% more expensive than household batteries. Battery prices are changing quickly so these statements are soon out of date.

Networks also want to install lots of street level chargers and earn regulated revenue. Good. However it seems like these will be single phase chargers and thus pretty darn slow. I may be wrong about this.

The difficulty has always been that networks are for better but mostly for worse regulated monopolies. It’s a cultural issue that tends to mean network management thinks it knows what the market wants but never has to actually go out and test the ideas.

Another problem for networks is they have to do what the AEMC (the rule maker) and the AER (the regulator) tell them. Under John Pierce, the AEMC didn’t have a clue. Pierce was probably brilliant at theoretical economics but the “power of choice” meter program has held Australia back. Marginal pricing for network tariffs was a sacrifice of reality to theory.

As can be seen below retailers ignore network tariff structures. They totally ignore them. As a result most customers never know what the network tariff is and so it can’t influence consumer behaviour.

That’s lucky because networks have persisted with largely irrational demand tariffs for residential customers. It may be they offer those tariffs because the AEMC makes them. Lordy, lordy.

So the question I ask myself as we head to a decarbonised electricity system is how can networks be better integrated into the market? Without letting them take advantage of their monopoly status? Can we make networks competitive? And in accordance with “Betteridge’s law of headlines”. the answers are probably no.

Networks and Consumer Energy Resources (CER)

Networks and their capabilities and role are not considered by AEMO other than as providing a mechanism to crudely curtail either demand or rooftop production in emergencies.

Networks are not part of the ISP. The ISP is a big enough thing already. Of course “the system” read AEMO, networks, generators, big brother wants to control your inverter, either crudely or via “dynamic envelopes”.

This could be done using consumer choice via tariff structures, but the retailers don’t offer those tariffs. Indeed, maybe we shouldn’t control the inverter and the rest of the NEM should adapt? I don’t think the answer is obvious, but what I do know is that system planners always want more control and that generally such control should be resisted.

Turning to the rule makers then.

As outlined on the AEMC web site, the AEMC is accountable to the Energy and Climate Change Ministerial Council (ECMC),. The ECMC isn’t a household term like COAG. Unfortunately, Angus Taylor and Covid combined to destroy COAG.

The ECMC has a set of priorities which sound fine and has 14 working groups. However, it’s really not produced very much in the way of Consultation output or Publications. So from an external observers perspective it’s easy to ignore.

For CER we start with The Energy Security Board which was essentially closed down and reconfigured as the Energy Advisory Panel (EAP) but in fact that body did not even meet in FY23. Still a report was released on ESB Letterhead in February 24 “Consumer Energy Resources and the Transformation of the NEM”

I quote from the Executive Summary :

The ESB recommends government convenes a CER taskforce, mandated with clear terms of reference to drive outcomes. The taskforce should focus on driving the following priorities across a 12 month period.

Despite my view of Paralysis by Analysis a working group was in fact formed and in swift order did in fact produce the “Powering Decarbonised Homes and Communities Report”

This laid out a series of priorities

| Workstream | Priority |

| Consumers | C1. Extend consumer protections |

| C2. More equitable access | |

| C3. CER information to consumers | |

| Technology | T1. Nationally consistent standards including EV to grid |

| T2. National framework for standards | |

| T3. CER communications | |

| Markets | M1. New market offers |

| M2. Data sharing | |

| M3. Redefine roles | |

| Power system | P1. Enable higher power transfers in the consumer grid |

| P2. Faster connection process including EV chargers | |

| P3. Improve voltage management | |

| P4. Incentivise distribution investment in CER | |

| P5. Redefine roles for power system operations |

And as has recently been reported, priority T1 around a standard for EV to the grid has been delivered on.

At first when you read the CER roadmap it seems like networks are ignored but as you get into the detail there is lots of stuff relevant to networks:

· Review of embedded networks.

· Changes to metering and metering standards to for instance have a CER data exchange including for EVs to better manage local networks, including increasing the pace of meter rollouts.

· Define the roles and responsibility of distribution level market operation.

· Define the role of DNSPs to achieve equitable two way market operations.

· Consider retail and network pricing to align incentives (as if) and Pathways identified to further incentivise didsitribuiotn network investment frameworks. This includes examination of the investment process.

· Develop a pathway to deliver network visibility to the market. (I think this would be helpful).

· Costs and benefits of improved voltage management.

As you might expect this is a suite of incremental policy changes.

Prior to examining the CER taskforce list of priorities I had developed my own priorities:

1. CER resources are not responsive to wholesale price signals; The CIS for instance won’t cover negative prices but no-one told households. Should rooftop solar face a price signal? I don’t think it’s clear. Maybe it isn’t a priority.

2. Networks are not and arguably cannot be incentivised to prioritise optimisation of CER to build microgrid resilience. A microgrid despite its many attractions, which I subscribe to, is from a regulatory perspective seemingly little different to an embedded network and look at the problems they have.

3. Consumers are insufficiently incentivised to install storage. I think this is where policy has to go.

4. The network kit” (hardware and software), the household kit and the economic framework aren’t there for EVs

5. Access to the grid is a big part of customer bills and CER tends to increase social inequity by distributing a bigger share of grid costs to consumers who don’t have CER. And such consumers are more likely to be socially challenged. (see I can do PC occasionally).

AEMC rule changes to date

The AEMC has made rule changes which allow larger organisations to have multiple service providers, and households can have separate metering for separate services. ITK has long argued that good measurement via better meters was obviously needed. In retrospect the previous “Power of Choice” metering policy held the industry back. This was obvious at the time.

Secondly, the AEMC has a draft rule change to integrate price responsive CER into the NEM. The trouble with this is that most CER resources are not price responsive and arguably it is not in their short term interests to be price responsive.

Networks set their tariffs but big retailers set prices

This section of the note shows that big Retailers just ignore network tariffs when they set their price plans.

Retailers basically have two plans. (1) Flat rate plan for customers without a modern meter (still about 50% of customers) and even though Ausgrid doesn’t offer a flat rate network tariff. (2) A time of use plan with peak, shoulder and off-peak which apply all year round. By contrast Ausgrid only has peak and off peak and peak is only applicable for days that fall within six months of the year.

The message here is basically that the network is irrelevant. It goes to my basic premise that the system in Australia sets networks up not so much to be a failure, because they are successful but ultimately to be irrelevant.

Ausgrid’s tariffs for small residential customers are:

Figure 1: Ausgrid residential tariffs. Source: Company

As discussed below demand tariffs are a solution to a non existent problem. There is heaps of spare capacity in networks thanks to previous investment and individual customer peak demand doesn’t coincide with system peak demand.

Regarding time of use it’s interesting to note that for Ausgrid there is only peak and off-peak and that peak only applies to six months of the year.

Figure 2: Time of use definition. Source: Ausgrid

By contrast lets look at AGL retail offers for customers in the Ausgrid distribution franchise.

I have to say looking at AGL’s plans is simple at first and then hard when you want to see the detail. The details are not even on AGL website but at the Government site.

Figure 3: AGL residential tariffs. Source:Company

Notice the Shoulder charge and these time periods apply every day in the year, so completely divorced from Ausgrid’s version of time of use.

If your house is in Ausgrid franchise but doesn’t have a time of use interval meter then you pay, looking at the Origin site 84 cents/day + 32 cents/kWh.

Again the network tariffs might as well not exist. That’s because the retailers know that most customers haven’t got the time or interest to look at demand charges and basically just want something as simple as possible.

I’ve only talked residential here but that is where all the retail profit is and also what the vast bulk of wires and poles assets are devoted to.

Network revenue is fixed, non solar customers subsidise solar ones

About 1 in 3 households in the NEM now have rooftop solar. Those households in general earn a respectable return from that investment. However, because of the way networks are regulated and remunerated the 2/3 of households that don’t have rooftop solar face even higher costs.

A contrary argument is that rooftop solar lowers the pool price of electricity and that benefits all consumers so in that sense customers with solar subsidise customers without solar. This may be true but it’s hard to prove.

Another contrary hypothesis is that rather than leading to more network investment (so that street level distribution can manage current flowing “upstream”) in fact rooftop solar reduces the need for new capacity in zone substations and other assets.

I would argue that in the end game a more distributed network will be “thinner” and more fault resistant and that power will be transferred over shorter distances, ie from one house in a street to another rather than from the Hunter Valley to North Sydney.

Conceptually, you could test that by looking at RAB investment in say Energex franchise v TAsNetworks after controlling for population growth, but life is too short.

Household batteries will reduce network throughput

Let’s say that household storage attachment rates, that is the number of batteries installed relative to the number of households installing solar grow from say 15% to 70% and there is some retrofitting as well. We can talk about how likely this is but it’s also interesting to think what it would mean for networks.

In the first instance, I’d expect a lot more solar energy to be consumed behind the meter. This would reduce both imports and exports from each battery connected point on the network.

Also as households move to EVs they will tend to increase the size of their solar installations so that the car can be charged from the rooftop during the day. You probably know someone that has already done this. If EV to the house becomes a thing a household could be become close to self sufficient at least during Spring and Summer.

So overall energy throughput through the network declines further. This is clearly shown in AEMO demand forecasts.

But the network revenue requirement is fixed if volume falls prices must rise. These higher bills fall disproportionately on consumers without rooftop solar.

Although it is not my concern in this note, it’s obvious that a significant portion of those consumers will be those that cannot afford rooftop solar or live in rented houses where the landlord has no incentive because the tenant pays the bill. And unit dwellers.

Last year, SACOSS released a briefing to the South Australian Energy Minister. I have taken a few figures from that report for this note. I do note this information is a year old now.

Let’s start with prices paid by voting households. Note prices not bills. Really, other than SA and NSW, it’s not too bad.

Figure 4: Median prices. Source: SACOSS

QLD and Victorian customers did not face higher prices, Those in NSW did. Quite clearly NSW consumers have seen the biggest % rise, the biggest bill shock with tariffs rising from 25c/kWh to 35c/kWh, or 20%.

The following figure shows how the price is made up, but does not show how the components have changed over time.

Figure 5: Price breakup 2023. Source: SACOSS

The network component includes transmission as well as distribution. The networks would no doubt, if they were writing this note, point out that in fact the average revenue per customers has declined over the past 6 years and in the case of NSW declined sharply.

Figure 6: Distribution costs. Source: SACOSS

The reason for the revenue fall is declining volumes and flattish (other than NSW/SA) wires and poles prices. Note that these costs are in real $ and reflect a bunch of factors including the changes in interest rates. Network charges rose in South Australia in 2024 by about 10%. Network costs also increased in NSW about 8%.

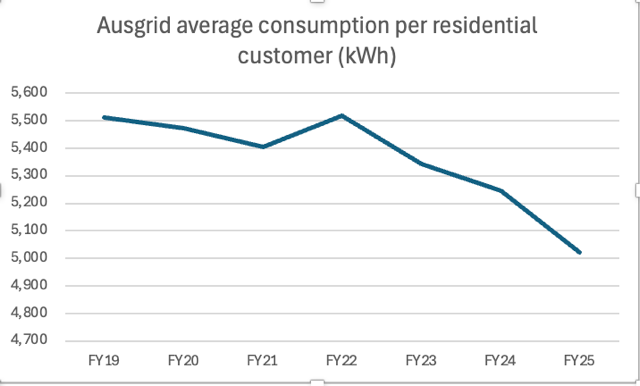

Over 6 years average consumption per residential customer has decline by 10% cumulatively but I expect that customers without solar have increased or held consumption steady.

Figure 7: Ausgrid consumption per customer. Source: RIN statement

It is the nature of this sector that no matter what happens to volumes there always seems to be the need for more capex and this pushes up the revenue cap and therefore prices.

To be clear behind the meter solar is now basically the equal second largest supplier of energy into the NEM at something like 11% of total energy supplied . At lunch time rooftop is the dominant suppler.

Figure 8: Fuels share of production. Source: NEM Review

Each year around say 2.5 GW of rooftop is added and that produces about 3 TWh of new energy.

The total quantity of consumer owned batteries is about 500-600 MW and the rate of growth at present is about 125 MW per year.

EVs have an average battery size of say 75 kWh. If an EV travels at a constant speed of 100 kph and consumes 18 kWh its power output is 18 kW. But the motors in EVs can typically produce 150-350 kW.

So from both an energy and a power point of view EVs could have a big impact on the grid. Obviously your average household won’t want 150 kW going through the fusebox (fire anyone) but the point is the EV can supply all the power its connection to the grid can handle.

Then there is the prospect of domestic demand response. For many years we have talked about turning the air con up or down in response to a price signal. In my opinion it’s going to be at best a very minor part of what’s needed. The control systems are hard, consumer acceptance is hard and so far it hasn’t been a starter.

Network costs are largely fixed, so let’s embed them in the property price

I’ve written before basically repeating the wisdom of Merv Davies former CEO of Ausgrid. In 2016 by accident I was in the audience of a presentation to the APVI given by him and despite all the work I have done in the sector every time I need to remind myself of what’s what I return to this presentation.

The main thrust of it was that nearly all network costs are sunk even in the medium term. And secondly that network assets are shared assets. At the time networks and the regulator were trying to force customers to have a maximum demand component to tariffs. But Merv and a number of other analysts pointed out that individual customer peak demand didn’t generally correlate well with system peak demand so what was the point.

Further households that could manage peak demand would use technology, eg batteries to minimise it, but people without the money couldn’t do anything. So household demand tariffs were perhaps a well intentioned but ultimately a dumb idea

So how should the costs be shared was a big question, but maybe not the only one. Still, it’s interesting to start with a simple topology diagram.

Figure 9: The Grid. Source: Merv Davies

Further, according to Merv, and he knew his stuff, in Urban Networks:

- Including sunk costs less than 50% of cost is driven by demand

- More than 50% is driven by location. Therefore:

“The spacing between customers drives most of the poles and wires cost, both high and low voltage and irrespective of demand.”

All the studies clearly showed that putting demand charges onto individual households would not achieve anything to help consumers. But did that stop the AEMC or the networks? Of course it didn’t. They now have demand tariffs, so far ignored by retailers.

These days if I was selling off Government owned networks. (1) I’d only issue a 25 year franchise lease rather than in perpetuity, (2) I would try and minimise the regulated asset base by building part of the RAB into the cost of the dwelling as a one time payment. (3) consider carefully the benefits and costs of having a regulated entity where the end users have little or no choice and little or no input into what is and isn’t built or incentivised to be built within the franchise territory.

For a reminder I now repeat a couple of figures from a note published in April this year.

Something like 2/3 of the price consumers pay each year for being connected to the grid represents a return on capital. The figure below is from Ausgrid’s as determined by the AER and looking forward. That’s the part of the bill that I speculate could be reduced with deep structural reform.

Figure 10: Ausgrid revenue: Source:AER

Equally, you can see that networks are growing demand charges and growing time of use charges. Delivery not involving time of use is declining. Eventually if this trend continues the retailers may eventually be forced to pay attention. Right now they ignore it.

Figure 11: Distribution revenue by function. Source: AER RIN statements

Finally, the sector assets can be broken up by function.

Figure 12: Distribution assets by function. Source: AER RIN statements

I argue as a debatable proposition that much of that RAB (regulatory asset base) say the distribution substations, underground assets, and the overhead network assets less than 33 kV could be sold to the properties serviced based on say the rateable property value and paid as part of the property purchase price.

If there are 10 million customers and say $60 billion of RAB it works to an average of $6000 per property. In addition customers would still be liable to pay for the remainder of the assets and running costs. Electricity bills would be way lower. No doubt there would be problems.

ENA proposals – interesting but poorly argued

In August, 2024, the ENA released proposals for how networks could support “decarbonisation of the electricity system and provide cleaner and cheaper solutions for all customers”.

The highest benefit policies identified in the study were in descending benefit order:

1. Facilitate solar plants being connected via the distribution grid instead of to higher voltage transmission;

2. Distributor owned batteries where some capacity can be shared with traders.

3. Street level single phase (7Kw) chargers;

4. Reduce ring fencing barriers for better coordination;

The proposals are interesting but the arguments were poorly marshalled, considered from too narrow a point of view and didn’t account for some contrary facts.

Looking at the idea of connecting utility scale solar, lets say 50-100 MW to the distribution grid instead of via transmission, LEK, the consultant to the ENA, show a graph that potentially has costs half those of connecting to transmission.

Figure 13: Connection costs. Source:ENA

So why isn’t this happening already? Well actually the ENA presentation states:

“There are inconsistencies in the costs charged to smaller generation projects connecting to a distribution network vs. larger projects connecting to a transmission network. This is due to regulatory differences in the rules regarding how much of the network capital cost to enable a connection (especially ‘deep network’ augmentations to unblock capacity constraints) are charged directly to the connecting generator. This imposes an undue burden on generation projects seeking to connect to sub-transmission networks and creates an economic disincentive for project developers to invest.”

At the moment a utility generator connecting to the distribution network has to bear 100% of the capital cost, just as a large consumer wanting to connect does, or pay a direct annual return to the network if the network’s cost of capital is lower, which of course it is.

By contrast traditional generator transmission costs become part of transmission operator (Transgrid in NSW) RAB and are passed onto all consumers and therefore not funded by the generator. However, the development of REZs is putting some of the costs more directly back on generators. So I doubt the above figure is the full story.

Network batteries have yet to demonstrate a value case

The ENA presentation claims that network batteries have a lower per kWh cost compared to behind the meter batteries. One of the problems with this is that the last time Ausgrid released the results of a study it showed a higher cost for network batteries. The data from the Government programs shown below also offers no support for community/network batteries being cheaper than household batteries.

What I would have found more interesting is a resilience and technical argument. Namely, the potential of community and household batteries to become isolated microgrids if the need arises. What contribution can distributed batteries make to distributed system strength, to fault current control? Can network batteries bid into the FCAS market?

It’s not just about the cost of the batteries but the installation cost. A distribution level battery requires a site, generally that site has a cost either explicit or implicit, requires some pre installation planning costs, requires post installation maintenance.

By contrast if you put in a Powerwall 2 the installer comes around, hooks it up, puts in the associated box to talk to the system, and its done. Half a day’s work when I had mine done and I expect its improved. Once installed no maintenance has so far been required.

In my opinion the Ausgrid study, although no doubt well intentioned, ended up persuading me that Ausgrid didn’t know what it was doing. However, even in W.A. where community batteries got their initial leg up, Western Power has only installed 13 and will only install more now its received an ARENA grant. On this topic the evidence has made me reconsider.

$200 million of community battery subsidies suggests household batteries are cheaper.

ARENA and the Federal Business Grants Hub are supporting $200 million of community battery funding. Round 1 of the Business Grants program approved $20 million at a median subsidy rate of $1200/kWh That, in fact, exceeds my estimate of the cost of a utility battery and is comparable to the installed cost of a Powerwall 2.

A summary of the grants awarded to date is.

Figure 14: Network/Community battery funding. Source: Govt (NB 370 batteries)

Again, I don’t set out to be either negative or cynical but when you take a subsidy and then claim network batteries are cheaper or subsidised its just a bit iffy. I do think network batteries have the potential to be cheaper, but then so do household batteries. Properly comparing costs would require a lot more data regarding power, warranties and the like.

The underlying truth to me, as at the time of writing this note, is it’s at least as and possibly more likely the community battery will be subsidised than the household battery. The 370 community/network batteries supported had an average full cost of $1280 kWh which is probably at least 10% more expensive than a household battery.

It’s still possible that network batteries could be cheaper thanks to “multiplexing” that is basically selling more than 100% of the capacity and creating more than one value stack but it isn’t a compelling picture.

Both residential and community/network batteries compete with transmission attached utility batteries. Many of these are now being built without subsidy but equally lots will take advantage of CIS funding to reduce the downside risk.

Even in the beloved world of carbon pricing or the less loved but still successful world of LRET certificates it still would be the case that batteries wouldn’t be eligible for any of that funding. They need their own program or be included in tax breaks as in the USA.

Street level chargers

Australia’s EV charging infrastructure is still a mess. I personally have a Chargefox, Evie. NRMA and Tesla app. Each app requires a separate registration, separate storing of card details. This is unsatisfactory. Tap and go like any other product seems superior. No app required. It’s unlikely this separate app strategy can be maintained for long, it’s just pointless.

If I was in Victoria I’d need an RACV app. Also, using the app at the charger takes time. The app has to work out where you are and then tell you the charger is free for use even though you are standing next to the blasted thing. More time is lost. Added up over 100s of 1000s of trips for all Australians it’s a a productivity loser. We are supposed to be the productive clever guys.

When we get to street level chargers that networks want to install in the 1000s the question then immediately arises of whether yet another set of apps will be required? Just to access single phase 7 KW power.

What about if the car wants to plug in and sell electricity back to the grid? Not going to happen at street level chargers is it?

However, I doubt that matters much. The fact is that many unit blocks, particularly older ones will need extensive rewiring to cope with the “grid in the unit block” and particularly in block charging. I expect strata committees face the new switchboard issue, face the issue that some units don’t want EVs etc.

Street level chargers compensate for that in a good way. They seem conceptually just like street lighting. Again the issue is that the capital cost will be socialised (spread over all users) of the network whether they have an EV or not. The cost of an app, or a tap and go system will also have to be recovered. As will maintenance. And the consumer will have to bring their own cable.

There will be another fight over the space occupied by an EV charger and whether it should be reserved. Generally street level parking is a competitive sport in inner Sydney.

Taking spaces away and reserving them for EVs will cause some angst. Then within the EV community will be the angst of owners who think the car occupying the space has been there too long.

Still it’s nothing new, they’ve been in Paris and London for a decade now. Here’s a photo I I took on a business trip in 2015, inLondon’s West end.

Figure 15: Street chargers London 2015. Source: Author photo