In yesterday’s piece, I dove into the mix of claims being used to present Australia to the world as a ‘climate leader’. One claim is hard to get off my mind. It’s the presentation of Australia’s 2030 Paris climate agreement target as particularly ambitious on the global stage.

It is, of course, not ambitious. Formulated off America’s 2030 target and simply pushed back five years, it is not aligned with ambitious climate action. As Climate Action Tracker writes,

“The government has shown no sign of scaling up climate action and is not planning to enhance its 2030 NDC target nor to adopt a net zero or any other stronger emissions reduction target. The government plans to meet its 2030 Paris Agreement NDC target by using carryover surplus emissions units from the Kyoto Protocol, significantly lowering actual emissions reductions, while other countries have ruled out using carryover”

This week, former finance minister and now incoming Secretary-General of the OECD, Mathias Cormann, claims that Australia’s 2030 target is world leading.

“The Australian emissions reduction target for 2030 seeks to secure a reduction by 50% on a per capita basis in emissions. By two thirds in terms of the emissions intensity of the economy. It’s one of the leading targets, you know, on that basis”

It took some time, but I finally found the origin of this claim. It seems to be a 2015 document created by the Australian government, obviously seeking to make Australia’s 26% reduction sound far more ambitious than it really is. “In terms of reduction in emissions per capita and the emissions intensity of the economy, Australia’s emissions intensity and emissions per person fall faster than many other economies. Australia’s emissions per person falls by 50–52 per cent between 2005 and 2030 and emissions per unit of GDP by 64–65 per cent”, claims the document:

These are based off data from 2015 – some countries, like China, have already proposed stronger 2030 targets. Population estimates for 2030 will be noticeably different now, particularly post-COVID. The United States is right around the corner from submitting a revised ambition for 2030.

These are based off data from 2015 – some countries, like China, have already proposed stronger 2030 targets. Population estimates for 2030 will be noticeably different now, particularly post-COVID. The United States is right around the corner from submitting a revised ambition for 2030.

Most importantly, the reason a percentage change of Australia’s per-capita emissions looks so great on a global stage is that Australia is starting from the absolute worst position on that metric, as illustrated nicely by Melbourne University’s Climate College, also released in 2015. Australia’s fall is among the steepest – but it still remains far higher than many other countries, in 2030.

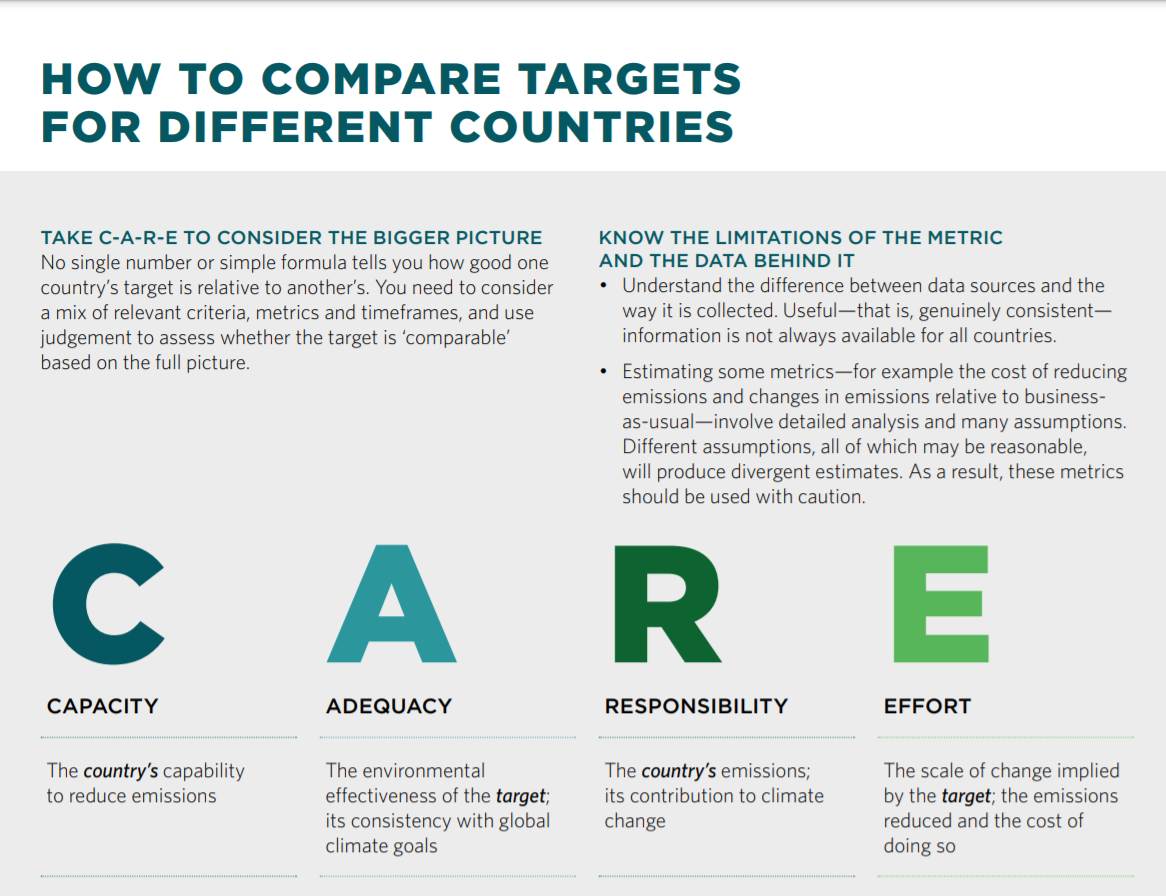

It is, in fact, relatively difficult to compare emissions reductions targets between countries. This is because a range of factors – like the capability of countries to decarbonise quickly, or how much has been emitted historically – mean straight numerical comparisons are almost always misleading. The long-suffering Climate Change Authority, the beleaguered government independent climate advice body that somehow managed to survive the Abbott era, tried firmly to remind people of this in another 2015 report.

Ultimately, the entire argument that having a weak target because other countries also have a weak target is both illogical and immoral. Australia exists within the Earth’s atmosphere and surrounded by the Earth’s oceans; it is vulnerable to the impacts of climate change just as other countries are. The safest option is to zero out the emissions Australia is responsible for, both domestic and those created when Australia sells fossil fuels overseas, while exporting as much clean energy (both literal and purely in terms of enthusiasm for climate action) overseas as possible.

Currently, if all countries adopted Australia’s approach, the world would warm by well over 2C, and up to around 3C, with disastrous impacts. What if Australia were to act too early on climate, while other countries lagged? Then Australia would be positioned with total energy independence, a wealth of direct experience with decarbonisation that other countries will be desperate to take up, and all the massive, immediate direct benefits of climate action (like cheaper electricity, cleaner air, safer homes, better transport and more resilient industries).

Last year, Australia officially refused to update its 2030 Paris target. It was justified, by Emissions Reductions Minister Angus Taylor, on these grounds: “On a per capita or emissions intensity basis, Australia’s 2030 target is more ambitious than those adopted by France, Norway, Canada, Japan or South Korea”.

When Australia is asked again to explain why it hasn’t updated its target later this year, there’s a high chance this excuse will come again.

Cormann’s usage of the 2015 per-capita comparison seemed to pass muster with a small audience of global leaders. Will it pass muster with the world’s climate experts, at the end of this year? Perhaps not, but it’s likely to serve as an important rhetorical defence of an utterly indefensible position.