A net-zero emissions Australia by 2050 will require a roughly 40-fold renewable expansion of the current generation capacity of the national grid, including the installation of almost 2 terawatts of solar PV, a new report has found.

The Net Zero Australia project, a research partnership between the University of Melbourne, the University of Queensland, Princeton University and Nous Group, explores the opportunities and challenges for Australia in transitioning to net zero emissions.

NZA’s Interim Results report, published on Thursday, outlines the scale of the challenge for Australia as it seeks to meet its climate and renewable energy targets, but also the significant nation-building opportunity that the shift to net zero represents.

The report’s finding are based on modelling of a number of different scenarios that the authors say “reflect the boundaries of the Australian debate” on how to get to net-zero emissions.

Most scenarios place no limit on the rate at which renewables can be built, but only one scenario, dubbed E+RE+, allows only renewables for new build generation. Or as the report puts it another way, gas and oil play a significant role in all modelled scenarios, “except if they are not permitted,” as in E+RE+.

But even according to the report’s slightly less ambitious E+ scenario, which models nearly full electrification of transport and buildings by 2050, no limit on renewables rollout, and a lower cap on underground carbon storage, the scale of the task ahead is daunting.

According to the E+ scenario, by 2030, when Australia is expected to get have an 80 per cent renewable electricity supply, there will be 98GW solar PV (135 projects), 49GW of onshore wind (79 projects) and 0.5GW of offshore wind (1 project).

A decade later, in 2040, the report puts total electricity generation capacity at about 15x the the current National Electricity Market (NEM), with 654GW of solar PV (782 projects) 130GW of onshore wind (187 projects), and 41GW of offshore wind – up from one solitary completed project in 2030 to 35.

And in 2050, solar PV gets into terawatt territory, with 1.9TW of solar PV (2,242 projects), 132GW of onshore wind (194 projects), and 42 GW offshore wind (36 projects) – all delivering electricity generation at about 40x the capacity of the 2022 NEM.

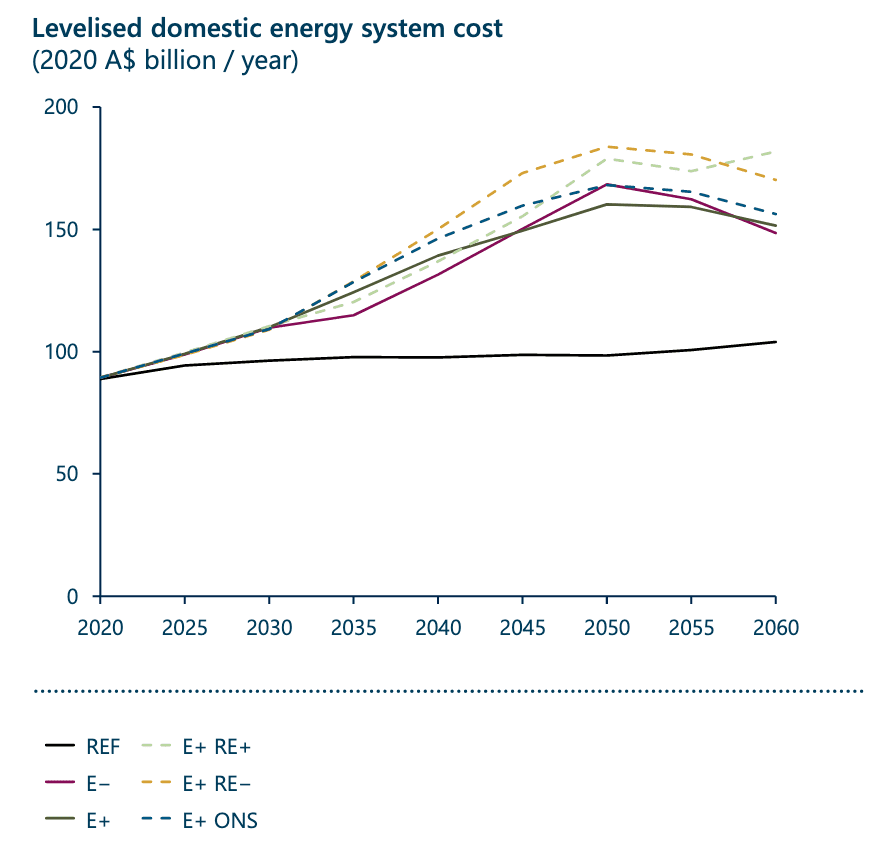

And of course, the cost of building all of this will be no small hurdle, either. According to the report, decarbonisation requires “much higher investment” – see chart below – than continuing to use fossil fuels.

But this “unprecedented capital investment,” the report notes, will also produce significant additional benefits and help avoid future risks promise to be both economically costly and – according to the science – environmentally devastating.

“The costs of inaction would be substantial if decarbonisation does not occur in Australia and globally,” the report says.

Achieving decarbonisation, however, will also reduce reliance on gas and oil imports, and thus exposure to price swings and supply constraints caused outside of our control – such as much of the world is experiencing due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Meanwhile, the report’s modelling suggests that domestic energy’s share of the gross domestic product will stay much the same as it is today.

“Domestic energy costs will account for a similar share of the economy in the transition to net zero as energy does now,” the report says.

“The shift to capital-intensive renewable electricity should reduce the economic impact of commodity price shocks. Placing fewer constraints on the transition (e.g. in the choice of energy sources) results in lower costs.’

On the commodities front, the report finds that Australia has everything that’s required to build a new “green” export industry to counter the decline in coal and gas exports, including green hydrogen products like ammonia and minerals used in batteries.

Green hydrogen, produced by all those terrawatts of solar and converted to ammonia or liquefied, is expected to be Australia’s largest clean energy export, with hydrogen from wind also expected to contribute.

And there will be jobs. Many millions of them – and mostly in the regions.

Net Zero Australia estimates between 1 million to 1.3 million new workers will be needed to reach net zero, with most of the jobs in growing exports across northern Australia, which would experience significant population growth.

Robin Batterham, chair of the Net Zero Australia steering committee, says the purpose of this week’s report is to work out how our targets can be achieved and to help governments and businesses to reach decisions on their

contributions to the task.

“Our findings show there’s no two ways about it – to meet net zero by 2050, Australia must transform,” Batterham said on Thursday.

“Major and long-term investment is required in new renewable generation, electricity transmission, hydrogen supply chains, and more. New skills and training is needed to capitalise on Australia’s clean energy potential. This will create new costs, benefits and opportunities.

“Clean energy exports are a major opportunity. Global demand for clean energy is currently uncertain, but Australian exports should be competitive. We stand to gain large export revenues and a million new Australian jobs, if exported energy stays around today’s level.”