The economic benefits of rooftop solar were up in lights in the latest report on the national grid by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, with solar households and small businesses shown to be paying around one-third less for their electricity than their non-solar counterparts – and not necessarily due to lower grid power use.

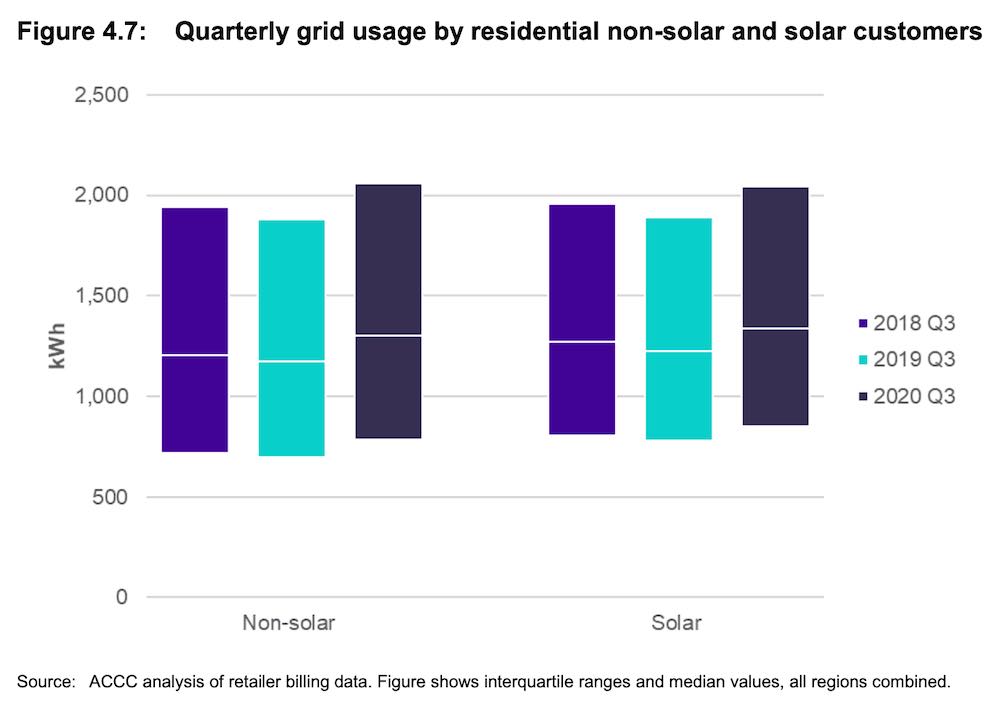

The ACCC’s latest Inquiry into the National Electricity Market, published on Friday, found that solar customers on the NEM pay the lowest effective prices for their power in 2020, even while solar households used, on average, slightly more power from the grid than non-solar homes.

The report found that in what was a year shaped by Covid-19 restrictions and impacts, NEM electricity consumption increased across the board for households, both solar and non-solar, with the draw from the grid slightly larger for solar homes (an 11% increase, year-on-year, vs 9%).

For small businesses, the report noted that customers without solar panels showed a marked decrease in their usage of grid electricity over the year, while businesses with solar showed only a slight decrease in grid electricity usage between 2019 and 2020.

But for solar NEM customers, the growth in which the ACCC report described as “one of the largest changes in the electricity sector,” the energy bill cost savings stand out the most.

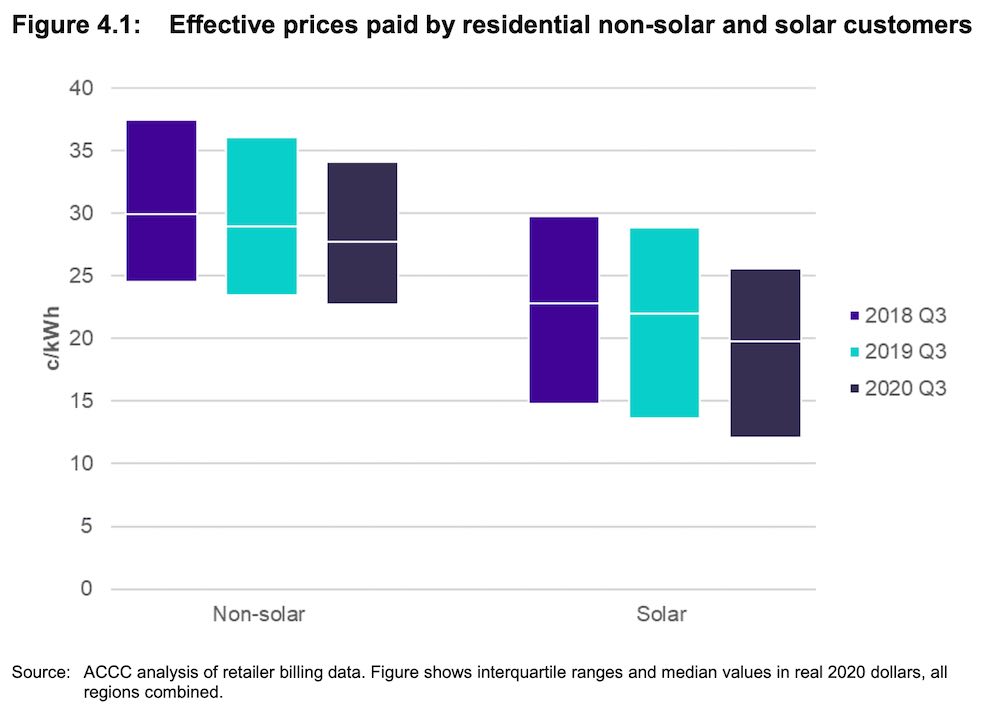

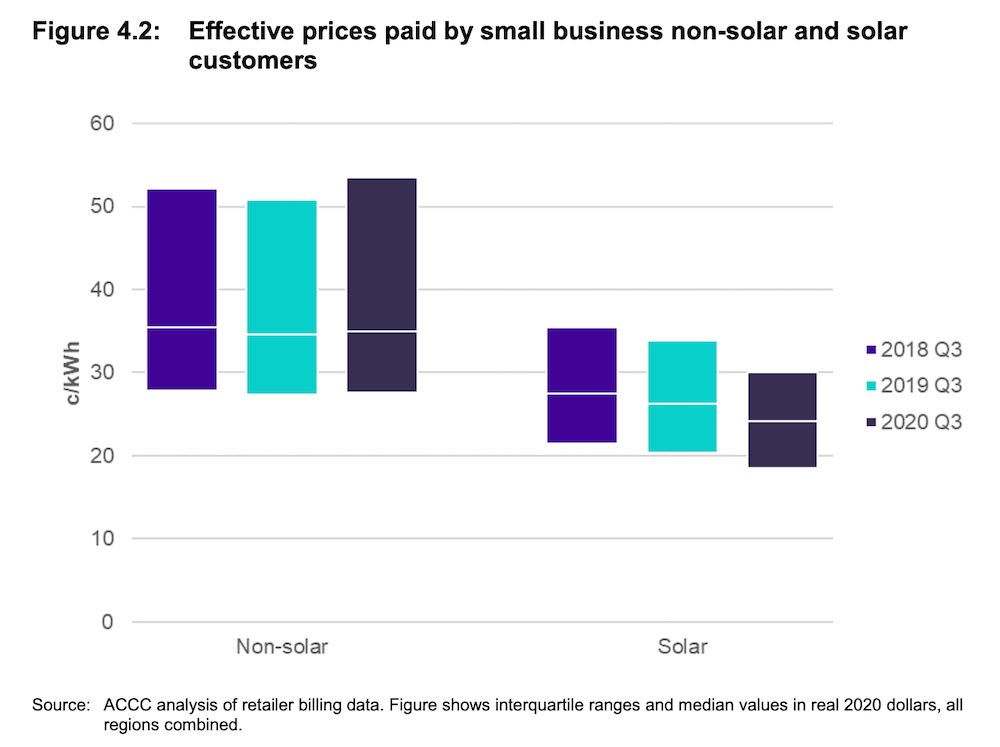

According to the report, solar customers across the four NEM regions paid a lower median effective price than non-solar customers for the year, with residential solar customers paying 7.9 c/kWh or 29% less than non-solar customers (figure 4.1), and small business solar customers paying 10.8 c/kWh or 31% less than non-solar customers (figure 4.2).

But here’s the kicker: The ACCC report notes that for residential customers, this price differential “was not driven by differences in grid usage … as residential solar customers used only slightly more electricity from the grid than non-solar customers.” (See Fig 4.7, above)

This means that the real driver behind the savings for solar households came from the feed-in tariff payments, or rebates as the report calls them, that they were receiving for excess rooftop generation sent to the grid

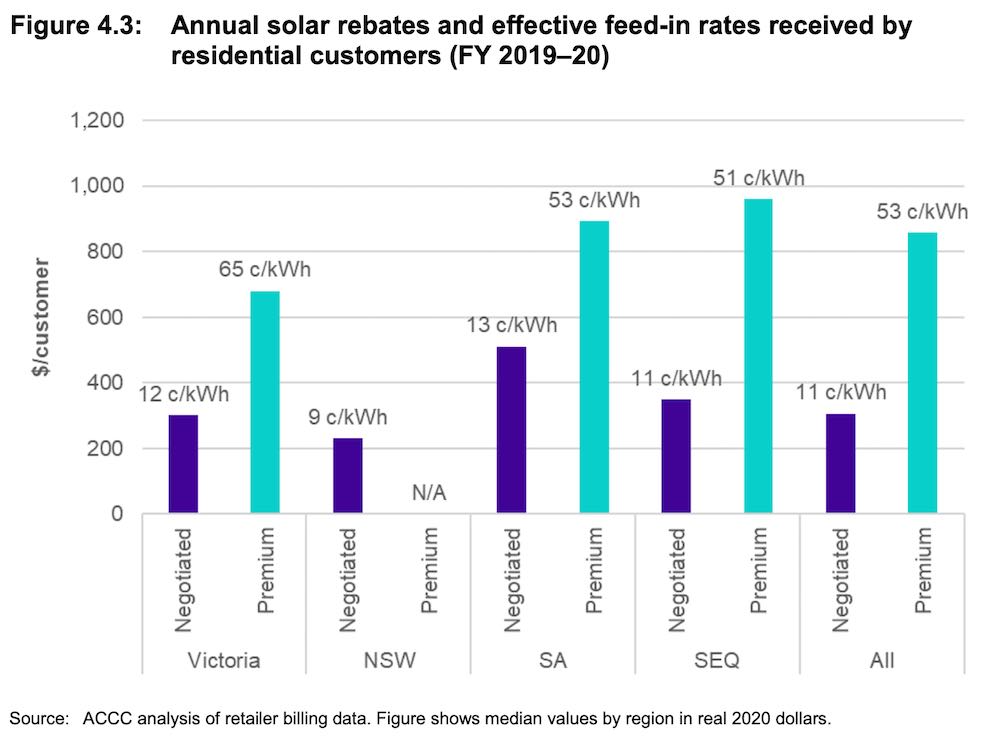

Granted, this statistic is undoubtedly skewed a little by the relatively small proportion of solar “early adopters” (they make up just 23% of all solar households, according to the report) on disproportionately higher FiT rates, ranging between 51c/kWh to 63c/kWh in some cases.

As you can see in the chart above, the median residential solar customer with premium rates earned $858 annually from rooftop generation sent to the grid. By comparison, the median residential customer with a negotiated tariff rate earned $307 annually.

Still, even the much lower, negotiated feed-in tariff rates undoubtedly still make up a great deal of a solar household’s annual electricity savings, as the report itself notes.

“Residential solar customers continued to pay much lower bills than non-solar customers (figure 4.9) despite using more grid electricity (figure 4.7). This is because of the benefit of rebates … In 2020 solar customers had a median quarterly bill of $253 in 2020, while non-solar customers had a bill of $347 ($94 difference).”

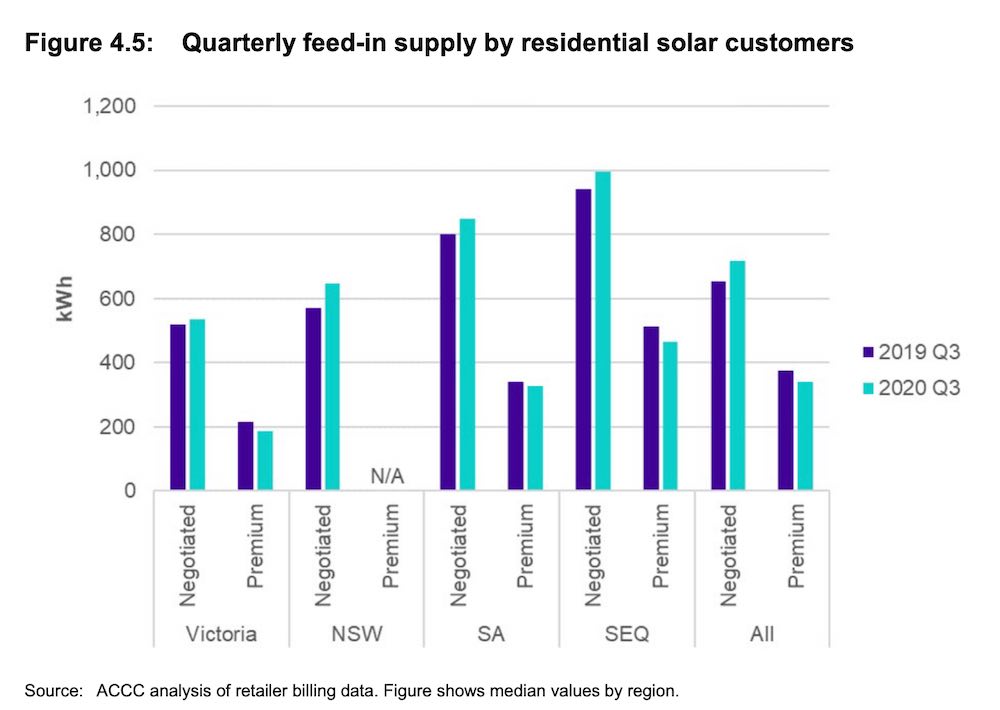

A look at the average solar household’s energy exports also helps paint a clearer picture. As chart 4.5 illustrates, solar households are sending increasingly high amounts of energy back to the grid as adoption of rooftop panels grows.

According to the report, “newer solar customers on negotiated feed-in tariffs supply more electricity to the grid than early solar adopters on premium rates… This is likely because system sizes for solar panels are much larger today than they were when early solar adopters invested in solar panels.

“For residential solar customers in 2020, negotiated feed-in tariff customers supplied 716 kWh electricity to the grid, while premium rate customers supplied 341 kWh (375 kWh difference, shown in figure 4.5).

“Customers on negotiated rates supplied higher volumes to the grid in 2020 than in 2019, while this was generally not the case for premium rate customers,” the report adds.

“This is likely due to negotiated customers investing in new solar capacity and also bigger systems being installed over time, whereas many of the eligibility requirements to remain on a premium rate prohibit augmenting the solar panel system, so the scope for premium rate solar customers to export more electricity to the grid over time is limited.”

All of this demonstrates why the push-back from the rooftop solar industry against the introduction of a rooftop solar export charge, for which a recent draft proposal from the Australian Energy Market Commission aims to pave the way.

Solar households and businesses argue that, in combination with diminishing solar FiT rates across the NEM – which are falling in line with wholesale power prices – an effective tax on solar exports to the grid would seriously diminish returns for households that have invested in solar power, perhaps even removing incentives for prospective customers, entirely.

On the other hand, the proponents of putting a price on solar exports as part of the future “two-way market” argue this will encourage the uptake of battery storage, an increase in solar self consumption and smarter use of solar exports, while protecting non-solar customers from having to help pay for the changes to the grid that network companies say rooftop solar uptake has made inevitable.

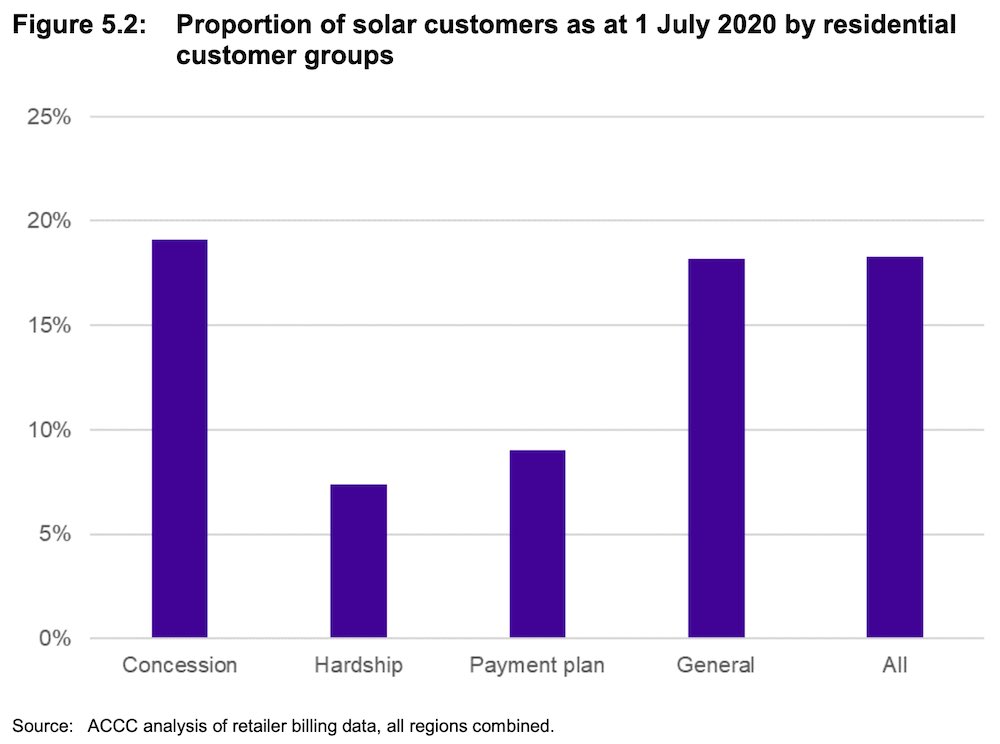

On that note, the ACCC report also demonstrates that uptake of solar, while most certainly not the preserve of the wealthy, remains far from equitably distributed in Australian society.

The ACCC found that hardship and payment plan customers paid the highest median quarterly bills out of all customer groups, partly due to a lack of solar panels among those groups.

As the graph above shows, hardship customers were the least likely to have solar panels at 7%, followed by payment plan customers at around 9%. The report says that these results go some way to explaining the high grid electricity usage of hardship and payment plan customers compared to general customers. But it’s also a story of the generally poor energy efficiency ratings of rental properties and community housing.

For more on this story, please read the original story at our sister-site, One Step Off The Grid .