As the roll-out of large-scale renewable energy struggles to advance against strong headwinds and governments look to extend the lifetime of coal fired power, there is another resource we need to better utilise in the energy transition – flexible demand.

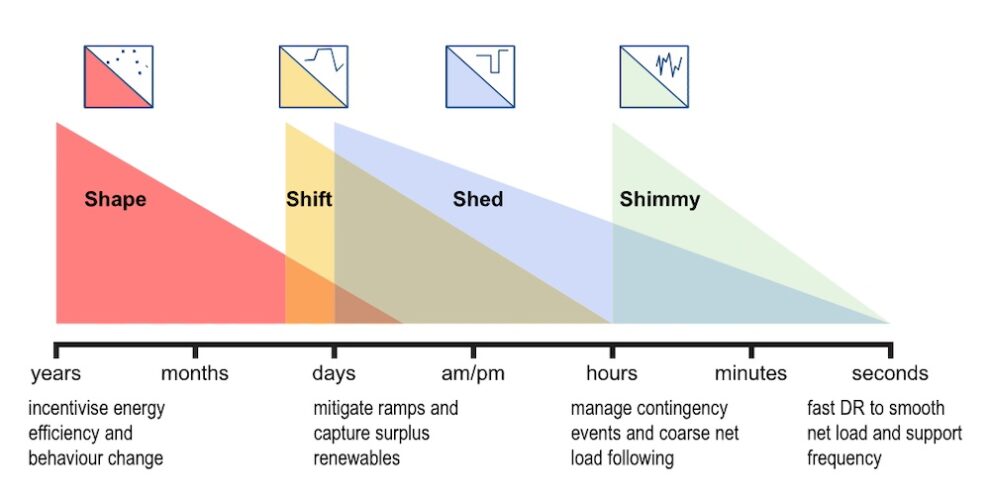

What is Flexible Demand? There are a range of different ways of creating flexibility in energy demad across different time-scales including;

– Shape and Shift: Bringing forward or delaying energy consumption, e.g. heating water in the middle of the day when there is surplus solar generation.

– Shed: Temporarily avoiding consumption when demand is very high, and the grid is under strain e.g., remote control to shave demand from a portfolio of air-conditioners.

Flexible demand is still emerging in Australia through an array of pilots, rule changes, and new programs and markets. There is currently no consolidated source of information on trends in flexible demand.

Consequently, ARENA commissioned the Institute for Sustainable Futures (University of Technology Sydney) to produce a ‘State of Play’ report. The report provides an overview of current flexible demand markets, policies and tariffs, in addition to mapping pilots seeking to demonstrate flexible demand technologies in homes, transport and buildings.

The State of Play report found that, while there are a lot of pilots and rule changes occurring, there is still a lot of work required to create the foundations and pathways to scale flexible demand.

Benefits of flexible demand increase with renewables

As flexible demand involves using existing network and generation assets more efficiently to match supply, it is generally lower cost than building new supply to match demand and enhances the reliability of the electricity grid.

As noted by Gabrielle Kuiper, while there is no single comprehensive study that estimates all the benefits of flexible demand, each of the major studies has found large benefits.

A study commissioned by ARENA estimated a savings range of $3 billion (lower renewables penetration) to $18 billion (high distributed energy resources) in generation and storage cost savings. This study did not include network savings but modelling by Baringa Partners for the Energy Security Board found distributed energy resources (including but not limited to flexible demand) could save $11.3 billion in network costs.

Based on international experience, it has been estimated that 5–11% or 15–20% of peak demand could be reduced with the right arrangements.

The largest opportunities lie in EVs and hot water – but information is scarce

A UTS study found a mix of efficient heat pumps and flexible resistive water heaters could alone save up to $6.7 billion in energy usage and $14.3 billion in avoided grid storage costs. There are now a wide range of pilots testing the operation of hot water systems, but there is a need for a coordinated roadmap to roll-out a low-cost source of flexible demand.

An ARENA report found electric vehicles (EVs) could provide one-third of storage requirements for the NEM but vehicle-to-grid (V2G) is in its infancy – most pilots have encountered a range of issues (e.g. technical standards that need to be updated).

There have been fewer pilots testing and measuring the scope for flexible demand in the commercial and industrial sectors and commercial fleets, but commercial buildings and refrigeration appear prospective as sources of flexible demand.

There is an opportunity to better use energy efficiency to support flexible demand

Federal and state energy efficiency schemes could be used to positively influence the uptake of flexible demand by, for example:

– Requiring that technologies installed through these schemes are ‘flexible demand ready’ (e.g. air-conditioning with demand response capability).

– Avoiding any disincentives for flexible demand technologies e.g. energy efficiency schemes provide incentives for heat pump hot water systems, but not flexible electric resistive systems, which are the best option for space-limited apartments.

– Creating positive incentives, e.g. the South Australian Retailer Energy Productivity Scheme has incentives for flexible tariffs or signing with aggregators to orchestrate devices.

In the report, we rate leading energy efficiency schemes on how they deal with flexible demand.

Energy Efficiency Schemes and Flexible Demand (FD)

| Jurisdiction | Scheme | FD link | How does scheme incorporate or link to FD criteria? |

| National | Green Star Buildings | There are credits for grid resilience which is related but does not directly cover FD. | |

| National | NABERS | Inclusion of FD in NABERS ratings is under consideration, but no planned changes have been announced. | |

| NSW | Energy Savings Scheme (ESS) | The ESS links to the Peak Demand Reduction Scheme and enables demand saving activities during peak periods to earn certificates. Air-conditioners also are required to be demand-response enabled to participate. | |

| Victoria | Victorian Energy Upgrades (VEU) program | Commercial battery storage systems are eligible. From 1 March 2024, all eligible hot water heat pumps must have an integrated timer. | |

| South Australia | Retailer Energy Productivity Scheme (REPS) | Switching electric hot water systems (heat pump or resistive) to solar sponge or off-peak block tariff.Switching household to time-of-use tariffs.Connecting new or existing battery, EV charger, heat pump or pool pump to VPP. | |

| ACT | Energy Efficiency Improvement Scheme (EEIS) | – |

Most customers don’t have an effective incentive for flexible demand – but there is a growing range of options

One of the barriers to the uptake of flexible demand is that most customers have relatively flat electricity tariffs that do not create incentives for shifting demand. The AER estimates that around one-quarter of consumers are on some form of ‘cost-reflective’ electricity tariff.

A range of flexible demand tariffs are emerging with incentives to shift consumption into the day (‘solar soaker’ tariffs) or EV charging out of evening demand peaks or import/export storage tariffs.

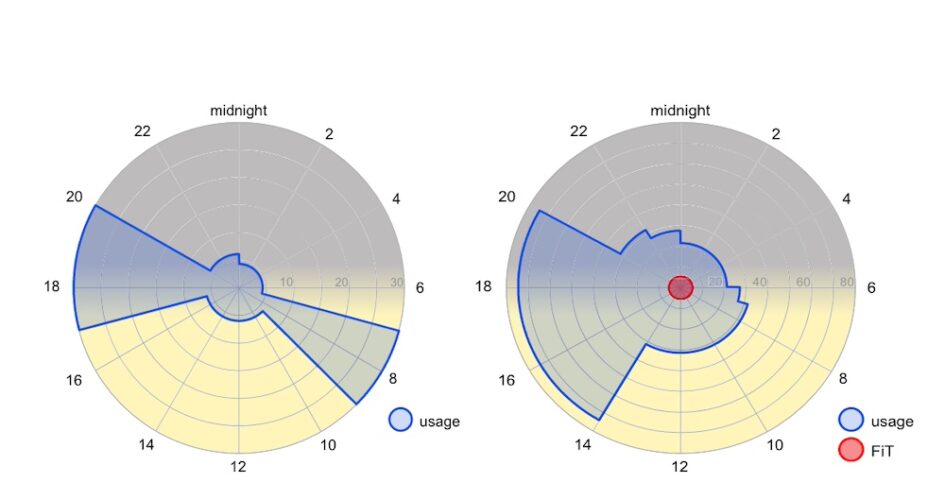

We have consolidated information on a wide range of network and retailer flexible demand tariffs with visualisations such as those below, which show the tariff (¢/kWh) at different times of day.

On the left, Ausgrid’s Residential ToU is an example of a ‘solar soaker’ tariff. This ‘bow-tie’ structure shows low-priced electricity during the day and much higher rates in the morning and evening peaks.

On the right, Engie’s EV Night-Time Saver rewards charging through the night, especially between midnight and 6am, while charging much higher rates between 2pm and 8pm.

Use of electric vehicle tariffs in ARENA pilots has shown promising results with many participants shifting their charging into late evening, and solar owners actively shifting charging into the day.

However, almost every study of consumer behaviour starts with the same disclaimer: our pilot participants were mostly ‘early adopters’ (mostly 50-something men who like tech).

It is notable that most of the energy system rule changes are focused on how to integrate flexible demand into the energy system, while surveys find consumer trust is low and the question of how to get ‘mainstream’ consumer participation is still to be solved.

Lack of clear pathways for scaling flexible demand

The existing schemes for flexible demand are small-scale.

– The Reserve and Emergency Reliability Trading scheme is used periodically for emergency demand response when the grid reaches its limit.

– There has been very low take-up of the networks’ Demand Management Incentive Scheme (only $11.5 million has been used out of a potential $1 billion in allowable expenditure) – though some networks are leading innovative pilots.

Only one provider (Enel X) and 65.3 MW of capacity is registered under the Wholesale Demand Response Mechanism (WRDM), which allows for demand response to be bid into the NEM as an alternative to supply – reflecting a range of factors such as measurement systems that only permit sites with flat consumption profiles (and therefore no solar).

It is difficult to develop a business case for flexible demand investments at a site or organisational level based on market schemes, as the returns usually depend materially on the number of future high price events in wholesale markets, which is unknown.

Consequently, international studies have found jurisdictions that provide revenue certainty have the highest levels of participation, especially through payments to have FD capacity available (‘capacity payments’).

The NEM now has the Capacity Investment Scheme. However, eligibility is limited to WDRM participants so the pathway for flexible demand to compete against batteries and pumped hydro is limited.

The Peak Demand Reduction Scheme in NSW is the only scheme with a pathway for scaling that includes a target, support mechanism and process for increasing the volume and types of activities over time.

While there is still much to learn about how flexible demand technologies and tariffs can work in real-world settings, the biggest change required is policy and regulatory reform to create mechanisms that can scale flexible demand to reach its potential.

Chris Briggs, David Roche & Ibrahim Ibrahim are from the Institute for Sustainable Futures (University of Technology Sydney)