The International Energy Agency has painted a bleak picture of progress towards a successful outcome in the climate talks in Paris this year, saying that the sum total of additional pledges made by leading countries have made little difference to the globe’s carbon budget.

The IEA says that the INDC’s (Intended Nationally Determined Contributions) so far pledged have managed to extend the world’s carbon budget – the level at which the world has a 50 per cent chance of keeping average global warming below 2°C, and so avoid runaway climate change – by just 8 months.

It says that, on current pledges, the world is heading to a temperature increase of 3.5°C after 2200, which would translate into higher average temperatures over land of around 4.3°C . “It is well known that the (pledges) will fall well short of what is needed to be on a path to the 2°C goal ,” it writes.

Still, the IEA says the game is not lost. The IEA notes that if the pledges are met, then renewable energy will overtake coal as the biggest source of electricity and account for one-third of electricity generation.

It lays out a new “bridging scenario” that it says can keep the door open to meet the 2°C target that all countries have signed up for. The scenario has major implications for Australia, because under the Coalition key climate and energy policies are being based on the IEA’s “new policies” scenario, which suggests no change.

The major part of the bridging scenario includes a peak in energy emissions – and a peak in coal consumption by 2020. It says this can be attained without any additional cost – mostly by removing the fossil fuel subsidies that distort the energy picture in many parts of the globe, increasing energy efficiency and phasing out the sort of inefficient coal-fired power stations that underpin Australia’s grid.

“A near-term peak in global emissions is also critical for credibility of overall climate efforts: if investors and policymakers see global emissions slow then peak, this in itself will be a hugely significant signal that the transition is underway,” it writes. As the graph above suggests, meeting the 2°C scenario will require an almost complete decarbonisation by 2050, well ahead of the 2100 commitment made last week by the G7 countries.

The IEA suggest that countries that have yet to submit INDCs (and this includes Australia) “could consider putting forward a mitigation goal that is at least in line with the scale of ambition reflected in the Bridge Scenario.”

It adds: “Countries that are willing to act early not only lower their transition costs, but play a significant role in demonstrating what is achievable and catalysing greater action elsewhere.”

The IEA notes that subsidised fuel prices and other government support for fossil fuels amounts to a $115 a tonne incentive to pollute, almost 16 times the prevailing price of emission permits in European carbon markets.

Fossil-fuel support systems represent 13 per cent of global emissions, compared with the 11 per cent governed by carbon markets, according to the group. Australia is not immune. In Western Australia, for instance, by the state government’s own estimates, the state is subsidising fossil fuel-based power consumption by $330 a household per year.

“If you dirty up the world, I will reward you. This is the message,” Fatih Birol, IEA chief economist, told Bloomberg in an interview in London.

The IEA also wants no new inefficient coal plants, and all the current ones to be phased out. It is particularly against so-called “sub-critical” coal plants. That describes almost the entire Australian coal fleet.

And whereas Australia is looking to cut the amount of renewables added to the grid, the IEA is pushing for a major increase. It says that under current scenarios renewable energy would account for one-third of electricity generation by 2030, up from one-fifth today, ahead of coal, gas and oil. Under the bridge and 450 scenarios (which meets the 2°C climate goal), wind and solar are the focus of investment.

“Renewables become the leading source of electricity by 2030, as average annual investment in non-hydro renewables is 80 per cent higher than levels seen since 2000, but inefficient coal-fired power generation capacity declines only slightly,” the IEA says of commitments made so far.

“With INDCs submitted so far, and the planned energy policies in countries that have yet to submit, the world’s estimated remaining carbon budget consistent with a 50 per cent chance of keeping the rise in temperature below 2°C is consumed by around 2040 – eight months later than is projected in the absence of INDCs.

“This underlines the need for all countries to submit ambitious INDCs for COP21 and for these INDCs to be recognised as a basis upon which to build stronger future action, including from opportunities for collaborative/coordinated action or those enabled by a transfer of resources (such as technology and finance).

“If stronger action is not forthcoming after 2030, the path in the INDC Scenario would be consistent with an average temperature increase of around 2.6°C by 2100 and 3.5°C after 2200. “

The IEA says that a peak in emissions can be achieved with proven technologies and policies and without changing the economic and development prospects of any region.

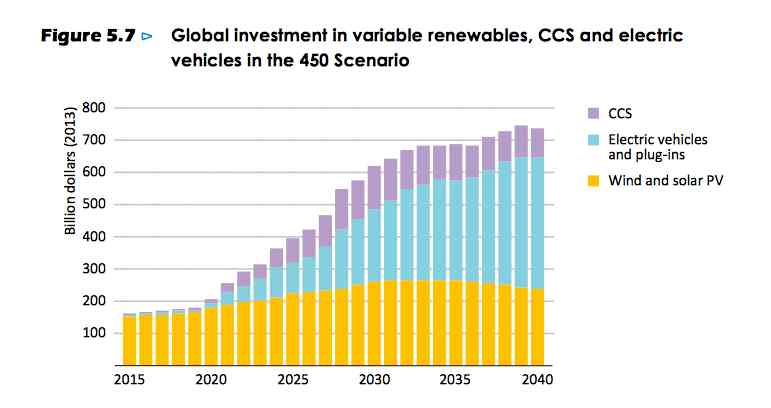

It notes that the bulk if investment needed to meet the 2°C target will be from wind and solar, which it defines as “variable renewables”. It predicts that the capacity of wind and solar will surge from about 450GW today to 3,300GW in 2040.

“Investment in variable renewables … far outpaces investment in other low-carbon technologies,” it says.

This in turn, creates a positive cycle, driving down the capital costs of new projects, making them increasingly financially attractive and so expanding market opportunities, in turn leading back to higher investment and greater deployment. Together, it says, variable renewables become a significant share of the power generation mix in many regions by 2040; they account for over 30 per cent of total generation in Europe, more than 20 per cent in the United States, Japan and India, and close to 15 per cent in Latin America and Africa.

The IEA, however, says its 2°C scenario is also highly dependent on carbon capture and storage. It says the costs of CCS to date are way too expensive, but thinks that widespread deployment will lower the costs. At the same time, it suggests a global carbon price of around $140/tonne will be needed by 2040. That would certainly bring CCS into competition with current coal plants.

But would it be enough to match renewables? Despite its favourable outlook on the share of variable renewable energy sources, the IEA remains highly conservative about its technology costs and its forecasts are dependent on technology cost estimates that many will find surprising, and others already out of date,

Its technology cost estimates for solar PV for instance – of between $US70 and $100/MWh for 2040 – are already being achieved in the Middle East, the US, and Latin America.