Sometimes you feel bad about shooting the messenger. It’s not good form. But reading a recent report from the Bureau of Resource Economics and Energy underlines a major part of the problem with energy policy and energy action in this country. And it’s all in the deliver of the message.

The particular message that BREE was delivering was the appallingly (my adjective) low rate of renewables penetration in remote and regional Australia – the areas of our sun-burnt and wind-blown country that really should be making a virtue of alternative energy sources.

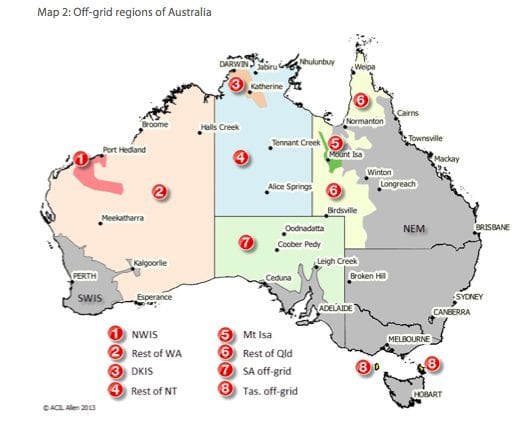

According to BREE, about 6 per cent of Australia’s total electricity output is produced in areas off the main grids in the eastern states (the National electricity market, or NEM) and the south west corner of WA (SWIS).

But get this. Of the 15,812GWh sent out in these “off-grid locations,” just 2 per cent comes from renewables. Most of this renewable output comes from hydro and solar accounts for less than 0.1 per cent of the output. The big red bits in the table below represents diesel generation.

According to BREE, there is just 3.4MW of solar in the two-thirds of the continent not covered by the main grids (in grey in map below). There is just 13MW of wind energy. Just over three quarters of off grid generation is for commercial or industrial use, just under a quarter for the 404,000 people who need power for residential use.

BREE concludes that this may create significant opportunities” for renewables “in the future”. It notes that “some” solar PV and wind technologies may become cost competitive with fossil fuels by 2030.

Oh, for goodness sake. Many of these communities trucking in diesel fuel are paying well over $400/MWh for their electricity. In some extremely remote areas are paying $1,000/MWh, some energy types tell me.

Solar is probably somewhere between $150/MWh and $250/MWh, although the best rule of thumb in outback areas – where transport, concrete and labor costs, and the availability of electricians are at a premium – should probably be around $300/MWh.

So, why isn’t it being taken up? The answer is for the same reasons exemplified by BREE – there is such a level of ignorance and conservatism that many consumers and users are simply unaware of the options, and/or they don’t trust it.

That’s a shame, because as Hydro Tasmania’s demonstration project on King Island has demonstrated, it is probably easier to reduce the amount of fossil fuel generation (and costs) on a diesel plant than it is on the main grid.

The BREE report uses data from 2011/12. But there has not been much progress since then. As we noted earlier this month, Ergon Energy’s annual report for 2012/13 revealed that less than 0.1 per cent of the generation supplied for remote and off-grid areas in its geographical area (97 per cent of Queensland) came from renewables.

Indeed, less than 1 per cent of its main-grid supply came from its own renewable sources. That is despite the management indicating that solar and storage would likely offer a cheaper solution than being connected to the main grid within 10 years. The Queensland subsidises the cost of that grid by $600 million a year.

Even cold, cloudy Tasmania has more than 13 times the penetration rate for solar in off-grid locations than the sunnier northern mainland states.

Off-grid solar and renewables (be it solar thermal and storage, or even wind and diesel) is now considered one of the most interesting markets in Australia, mainly because of what seems to be the no brainer economics of the proposal.

But as any project developer will tell you, there are considerable barriers to entry, and it’s not just a matter of ignorance and trust.

One is the level of subsidy for fossil fuels. Diesel generators get a massive rebate which accounts for one third of their costs, and it is not entirely clear whether those benefiting from the subsidy are the suppliers or those paying for electricity.

Other barriers include laws such as the Pastoral Act, which until recently made it illegal for owners to be involved in biomass crops on grazing land. Then there is the cost of supplying, the transportation and the labor costs.

Finally, there is the question of finance and rates of return. Mines often have shorter life spans than a renewables installation. And off-grid renewables might offer generous rates of return, but in an industry which can get even higher rates of return by building a new conveyor belt, getting the attention fo centralised accounting people is tough.

This is one of the reasons why the Australian Renewable Energy Agency has made a big commitment to break down some of those barriers through its off-grid and remote energy programs.

It also believes that the economics of the technology are something of a no-brainer, and if it can lead the horses to water and show how it can be done, then the take-up could be rapid. After all, the commodities market is no longer so buoyant that mining groups should be happy to ignore power costs or fuel price risk.