Network company Ausgrid’s controversial proposal to install and run neighbourhood-sized batteries and rooftop solar in two Sydney areas has been waved through by the regulator.

The distribution network service provider (DNSP) has secured a waiver for the Community Power Network pilot, a project that will incentivise up to 70 megawatts (MW) of new solar on commercial and industrial rooftops, and store and discharge excess production in up to 130 megawatt hours (MWh) of neighbourhood batteries.

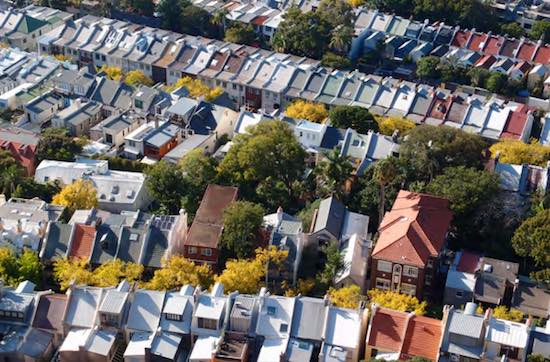

The pilot will be run in Mascot-Botany in Sydney and Charmhaven on the Central Coast, the latter chosen for being more residential, while the former mixes social housing, renters, and large-scale warehouses.

The project required a waiver, which it got from the Australian Energy Regulator (AER) last week, from ring fencing rules that prevent DNSPs from participating in competitive markets.

The AER has been waiving some ring-fencing rules to allow for testing of new products, services, and business models in a way it says can foster innovation while protecting – and ultimately benefitting – consumers.

To this end, the Community Power Network pilot will be under the policy-led “sandboxing” approach launched by the regulator in February.

Australia’s DNSPs are monopolies that are normally restricted from wielding their market and information power in competitive markets. In many other countries, networks are also the retailers and allowed to engage with consumers, and the Australian networks would very much like to be in the same position.

They are pushing the boundaries, with network operators in NSW and Victoria testing the limits of what they can offer for distributed energy resources such as batteries and electric vehicle charging – all under the guise of understanding the impact on the grid or enabling better ways to manage these resources.

Unleashing the data

While critics say the pilot as a whole isn’t doing anything the private sector can’t already do, there is one condition that may help to drag both DNSPs and energy planning into the modern world.

Ausgrid has promised to publish spatial energy plans for the two locations, and will be required to run a third to provide a point of comparison and keep it updated every quarter.

Spatial mapping uses data already held by DNSPs around current and projected household, commercial, and industrial energy use, important information that can be used for everything from deciding where a new battery should go to where might be a good location for targeted resource orchestration.

Critics of the pilot say it’s something DNSPs should be doing anyway.

But while the option of a third site will open up a wealth of data to commercial entities, the AER says it must also be like-for-like in terms of size and diversity of residential and consumer and industrial mix.

Importantly, it must also offer the same conditions to anyone who wants to operate there, from battery tariffs to connection timeframes and fees.

“This offers a structured way to observe how detailed spatial information affects CER [consumer energy resources] deployment decisions for both networks and service providers in the competitive market,” the AER said in its final decision.

“This plan will provide Ausgrid with feeder-level visibility of constraints and opportunities, down to the voltage and balancing limits of individual circuits.

“This allows distributed resources to be targeted to locations where they can relieve pressure on the network, avoiding future upgrades.

“As the plan evolves throughout the trial, it will show how local conditions change as more distributed resources are added, whether constraints emerge or ease and how responsive the model is to these changes.”

Gold-plating risk

The conditions may not go far enough to appease the retailers, consultants and community groups who linked up to oppose the pilot, however.

The AER removed a $42.8 million financial benefit ascribed to emissions reduction from the proposal, leading Nexa Advisory founder Stephanie Bashir to question just how much of a benefit the pilot provides now to consumers.

“There is no cost–benefit assessment, no RIT-D, and no evidence that this model will improve affordability or efficiency,” she told Renew Economy.

“Ausgrid’s largest claimed benefit — $42.8m in emissions reductions — was removed by the AER, yet no revised benefit case was required. The trial proceeds without a valid economic justification.”

Bashir says the pilot poses a risk of allowing Ausgrid to gold-plate its revenue streams by over-investing in what is actually needed, then passing the cost on to consumers.

Questions also remain about where Ausgrid will find the money to pay for the pilot, and about the risk to consumer choice if their network operator also becomes their electricity supplier and solar installer.

It is not allowed to disperse the cost across its whole customer base, because the revenue it’s allowed to take from its regulated asset base (RAB) has been set until 2029.

If you would like to join more than 28,000 others and get the latest clean energy news delivered straight to your inbox, for free, please click here to subscribe to our free daily newsletter.