Australia will need nearly three terrawatts, or 3,000 gigawatts, of wind and solar if it is to meet its goal of a net zero economy by 2030, a plan that could cost up to $9 trillion, according to a new study.

The astonishing numbers are revealed in a new report – Net Zero Australia – put together by Melbourne University, the University of Queensland, and the Nous Group, and released on Wednesday.

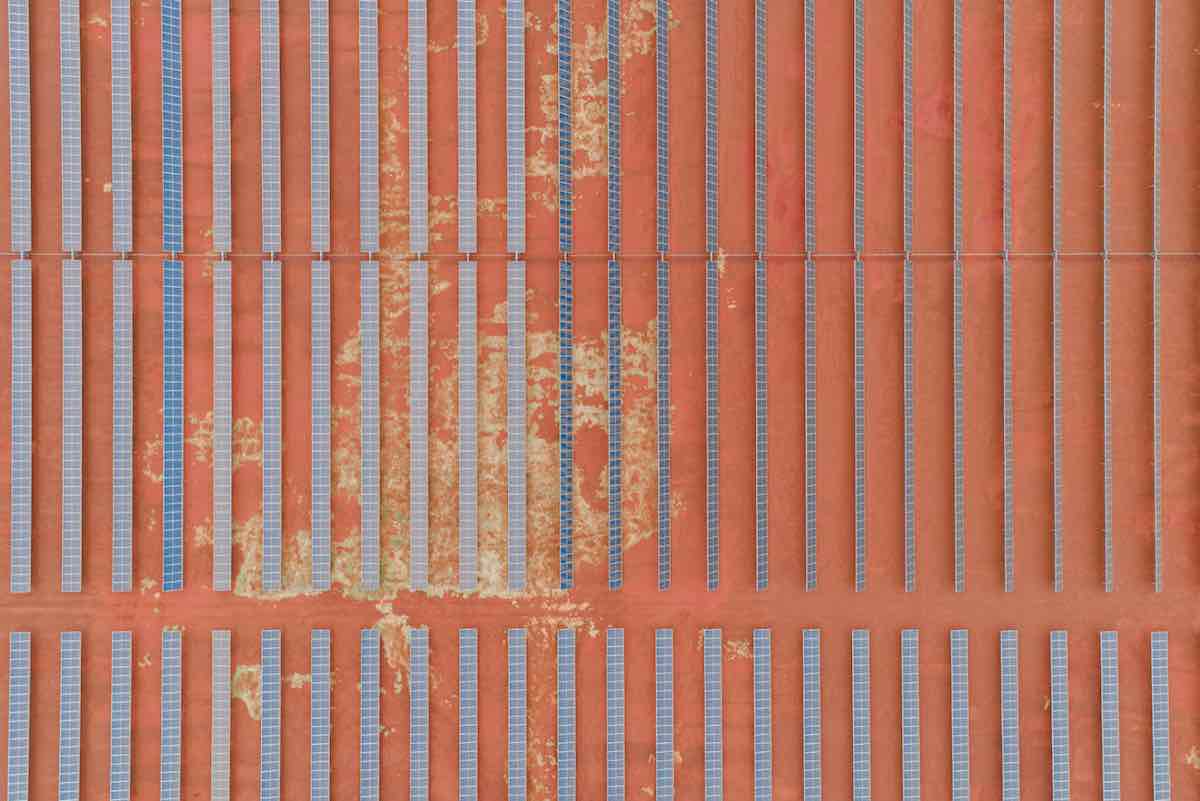

To put the 3,000 gigawatts of wind and solar in some context, Australia currently only has about 30GW of large scale wind and solar across the country. So it has a lot to do.

The report underlines the scale, complexity and cost of the net zero challenge, which it describes as a “once-in-a-generation, globally significant and nation-building opportunity” that will transform the domestic economy, and Australia a key player in global decarbonisation efforts thanks to the exports of green energy and metals.

But it won’t be easy.

First off, Australia will need to triple the power capacity in the National Electricity Market’s by 2030 to be on track for net zero by 2050, and it will ultimately need to increase the size of the NEM 40 times over to meet that economy wide and clean export target.

“(The energy transformation) requires us to grow renewables as our main domestic and export energy source such that by mid-century we have 400-500 GW serving our domestic energy system and potentially several thousand GW producing energy exports, compared to roughly 25 GW today,” the report says.

Australia will also need to establish a fleet of batteries, pumped hydro energy storage and gas-fired firming that is larger in capacity than its domestic energy system now, and greatly increase electrification and energy efficiency across all sectors, including EVs and replacing gas-fired heat in homes and businesses.

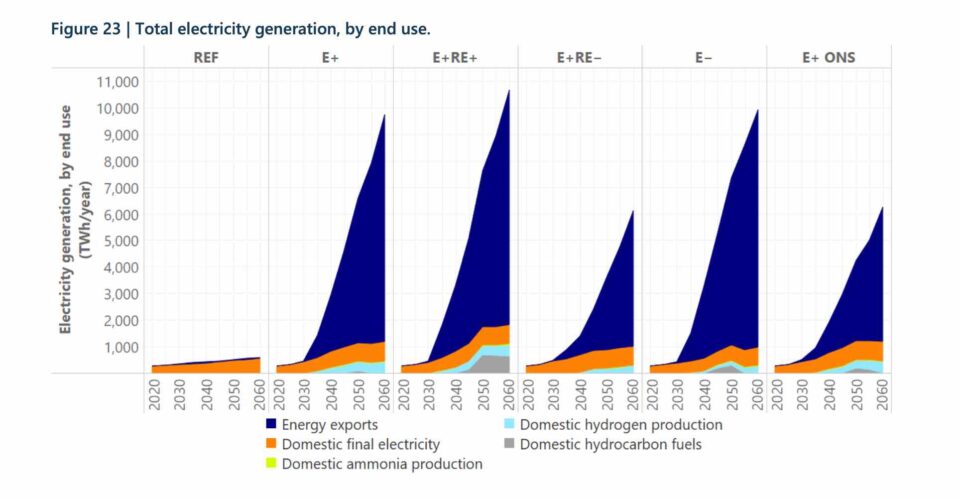

The report models six different scenarios – ranging from a reference point and slower electrification, to rapid electrification that sees no impediment to renewables (E+ RE+) to constrained renewables (E+ RE-) and local “onshoring” (E+ ONS) which makes the sensible conclusion that Australia should use clean energy to export refined products such as iron and aluminium rather than lumps of coal, minerals and fossil molecules.

Some of the scenarios appear designed to satisfy some of the key sponsors of the report, including gas companies APA and Dow and Worley, Andrew Forrest’s Minderoo Foundation (big interest in hydrogen), and other organisations who favour carbon capture and storage.

Their big bet appears to be that the deployment of wind, solar and storage is somehow constrained by infrastructure, land access/, labour and other supply issues. That, they say, will create opportunities for more gas, CCS, and offshore wind.

Nuclear is written off as too expensive, and it says that even it can achieve substantial cost reductions and renewables were somehow constrained it would likely only play a limited role at best.

It should also be noted that while the report focuses heavily on costs and opportunities, it doesn’t model the cost of inaction, or fossil fuel supply constraints, and it draws a straight line pathway to zero emissions, when most analysts reinforce the need to do much of the easy stuff quickly for a 1.5°C outcome.

Still, the report is remarkable when you consider that little more than a decade ago the likes of Beyond Zero Emissions were rolling out 100 per cent renewable scenarios and being widely mocked for doing so.

Now, even what could be described as the “energy establishment” accepts that the transition to wind, solar and storage is inevitable, and desirable, even if there is still debate about the scale and timing. This report acknowledges that in every scenario, fossil fuel generation in Australia will slump by 80 per cent by 2030.

The report notes that between 40GW and 80GW of new wind and solar will be needed every five years, or up to five times the pace of the recent rollout of wind and solar in Australia’s main grid.

That, though, is just with the domestic energy system in mind. What is needed to meet clean exports and replace the current focus on coal and gas exports is simply astonishing – upwards of 10,000 terawatt hours a year, or around 50 times more than what is currently produced on the country’s main grids.

That supply will inevitably come predominantly from wind and solar – the only point of debate is the extent to which CCS, hydrogen, gas and offshore wind will seize part of the market.

Professor Michael Brear, the director of the Melbourne Energy Institute at the University of Melbourne, says the modelling makes clear that renewables and electrification, supported by a major expansion of transmission lines and storage, are keys to reaching net zero.

“But we will need an all technology, hands on deck approach. That includes a large increase in permanent carbon storage, deep underground and in vegetation, and a doubling of gas-fired power capacity to support renewables and energy storage.

“Our modelling finds that there would be no role for nuclear energy unless costs fall sharply (to around 30% lower than current international best practice) and renewable energy growth is constrained.”

The major points of contention might be the estimated costs of abatement – upwards of $300/tonne – which probably should be clarified as applying to only the hardest parts of the energy transition. And considering where we have come from in the last decade, likely to fall dramatically before they are addressed.

And there is also the projections of CCS, which seem to be used to justify a push for “blue hydrogen” (made from fossil fuels, and gas in particular), and gas generation in general, even up to 2060 in some scenarios. That does not appear consistent with a 1.5°C world, a target which the report does not even discuss.

It is interesting to note that a net zero analysis produced by Baringa on behalf of the Clean Energy Investor Group suggested no role for CCS, at least in the domestic economy.

At least, however, the nuclear question has been effectively buried, although it would be surprising if the conservative media and the federal Coalition took much note.